A bill now before the state Senate, House Bill 590, would make a simple but sensible adjustment to an already good regulatory policy. The Regulatory Reform Act of 2013 included a reform known as sunset provisions with periodic review of administrative rules. It is a proven effective way of removing red tape from a state’s administrative code.

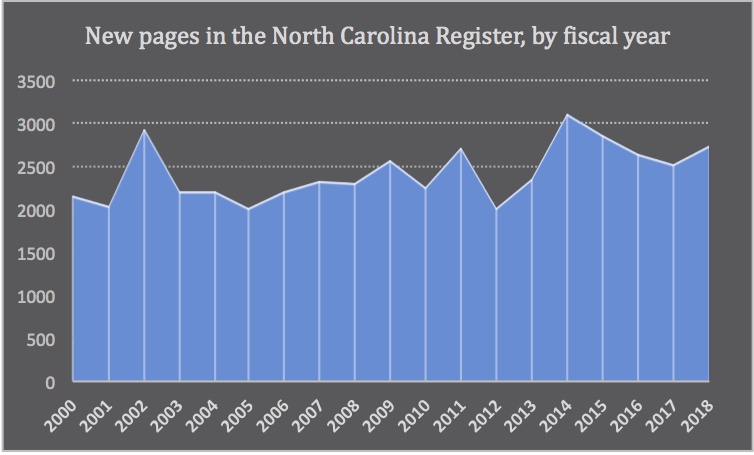

Rulemaking is an ongoing process, and red tape is an inevitable byproduct. Here is a snapshot of rulemaking activity in North Carolina this century, as measured by the page counts in the North Carolina Register (which gives information on agency rulemaking, executive orders, proposed administrative rules, contested case decisions, notices of public hearings, etc.):

Trend in State Regulatory Activity, 2000–2018

The growth in the total stock of state regulations — and especially of red tape — has significant, negative economic ramifications:

State regulations have been estimated to cost the private sector in North Carolina up to $25.5 billion in a single year. Such a tremendous toll on private enterprise, especially in terms of deadweight loss, is why it is vital to ensure that state regulations are (1) carefully made, and also (2) periodically checked to see if they’re working, still needed, outdated, or more trouble than they’re worth.

That’s what sunset provisions with periodic review of state rules is designed to do.

At last count, this process had removed one out of every eight rules reviewed. That is impressive on its own. At the same time, it could be doing even more, as state leaders have acknowledged.

Here is how the process works right now. Any rule that is not reviewed by its originating state agency within 10 years after it was adopted would be repealed (sunset). A rule that is reviewed is placed in one of three categories (sometimes called “buckets”):

- “Unnecessary.” A rule the agency no longer finds necessary. It gets repealed.

- “Necessary with substantive public interest.” A rule the agency considers necessary and has attracted public comment within the past two years. It must go back through the rules adoption process as if it were a new rule.

- “Necessary without substantive public interest.” A rule the agency considers necessary and hasn’t attracted public comment. It is automatically re-upped.

So about one out of every eight rules was being repealed as “unnecessary.” The problem with the setup is what happened to the others. Why shouldn’t they all go back through the rules adoption process as if they were newly proposed rules? That would serve the public interest in scrutinizing rules better.

Instead, over 60 percent of state rules were getting categorized as “necessary without substantive public interest” and therefore automatically re-upped, without any additional scrutiny. Only about one-fourth of rules considered necessary were subject to readoption.

A widely acknowledged simple fix

The simple fix to the process would be to get rid of the third category, which is behaving like a loophole. Unnecessary rules would still be repealed. But there’s no need to create distinctions among rules considered “necessary.” They should all go back through the rules adoption process as if new.

Garth Dunklin, chairman of the Rules Review Commission, sought this reform in his remarks to the Joint Legislative Administrative Procedure Oversight Committee in late 2016. As Carolina Journal reported,

“When 61 percent of the rules that are going through this process are staying in the code with no change, they’re not getting the full exposure to public comment or careful examination,” Dunklin said. That “bothers us from a policy standpoint.” …

Eliminating the “middle bucket” would bring the law closer to its original objective, “simply that every bill in the code would expire on certain dates, and have to be readopted,” similar to a process other states use, Dunklin said.

“The concept there was to make agencies pick up and look at their rules, and examine their continuing usefulness and efficacy, expose them to the process of public comment that is a part of our rulemaking process,” Dunklin said. Outdated rules could be stricken from the code, and the remaining rules could be improved with renewed scrutiny.

Dunklin noted that many agency heads who were asked by a Rules Review Commission member what a particular rule was, “the response, disturbingly frequently, would be, ‘I’m not really sure, it’s just always been there,’” he said.

Lawmakers agreed, and in 2017 both chambers of the General Assembly passed versions of a bill (House Bill 162) that would have made that simple fix. Unfortunately, disagreement over other parts of the bill prevented the conference report from being adopted.

That’s why an idea that had broad bipartisan and bicameral support still isn’t law. This year it could be. HB 590 would remove the loophole, and it easily passed the House earlier this session, 114-0.

It’d be better to have a stronger way of revisiting and reviewing old rules to make sure they’re not creating more harm than good. “I’m not really sure, it’s just always been there” isn’t a good enough reason for leaving an obstacle in place.