History told through tales of impersonal forces, broad-based social and technological change, hits an occasional obstacle — that great man or woman who seems indispensable to the story.

History told through tales of impersonal forces, broad-based social and technological change, hits an occasional obstacle — that great man or woman who seems indispensable to the story.

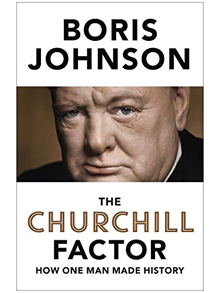

Winston Churchill is one such obstacle. And London Mayor Boris Johnson demonstrates Churchill’s indispensability to the story of the 20th century in the book The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History. Fifty years after the great man’s death, Johnson sets out to remind his countrymen why they can thank Churchill for much of the liberty and progress they enjoy today.

This is not a standard-issue biography. Johnson’s style is chatty and full of slang. He leaps back and forth in time, focusing on periods of Churchill’s life as they relate to broader themes: his reckless heroism, love of publicity, and steadfast belief in the British Empire, among others.

The author also devotes a not insignificant amount of space to describing his own interaction with the Churchill story. He visits Churchill’s home and office settings, cemeteries and battlefields, even modern-day businesses named for Churchill. Political observers have noted that Johnson, an eccentric character with some degree of Churchillian charisma, has produced this book just as the author enjoys buzz as a potential candidate for the prime minister’s job that Churchill held on two separate occasions in the 1940s and 1950s.

Regardless of Johnson’s political intentions, his book paints a flattering portrait of Churchill’s significant accomplishments. Consider the impact of Churchill’s decision in 1940, against almost all advice, to reject any prospect of a settlement with Hitler to avoid an attack on the British Isles.

If Britain had done a deal in 1940 — and this is the final and most important point — then there would have been no liberation of the continent. The country would not have been a haven of resistance, but a gloomy client state of an infernal Nazi EU.

There would have been no Polish soldiers training with the British army, there would have been no Czech airmen with the RAF, there would have been no Free French waiting and hoping for an end to their national shame.

Above all there would have been no Lend-Lease, no liberty ships, no Churchillian effort to woo America away from isolationism; and of course there would have been no prospect of D-Day; no heroism and sacrifice at Omaha Beach, no hope that the new world would come with all its power and might to rescue and liberate the old.

The Americans would never have entered that European conflict, if Britain had been so mad and wrong as to do a deal in 1940. It is incredible to look back and see how close we came, and how well supported the idea was.

I don’t know whether it is right to think of history as running on train tracks, but let us think of Hitler’s story as one of those huge and unstoppable double-decker expresses that he had commissioned, howling through the night with its cargo of German settlers.

Think of that locomotive, whizzing towards final victory. Then think of some kid climbing the parapet of the railway bridge and dropping the crowbar that jams the points and sends the whole enterprise for a gigantic burton — a mangled, hissing heap of metal. Winston Churchill was the crowbar of destiny. If he hadn’t been where he was, and put up resistance, that Nazi train would have carried right on.

Plus Churchill proved both prescient and inspirational.