In 2014, the Manhattan Institute published a provocative report called Overcriminalizing the Old North State. The authors, Jim Copland and Isaac Gorodetski, described the rapid and disorganized proliferation of new crimes in North Carolina between 2009 and 2014, including many strict-liability crimes created, not by the legislature, but by various administrative agencies and occupational licensing boards. The use of obscure and little known criminal laws to regulate ordinary business practice, they suggested:

Discourages entrepreneurship, especially among those who are self-employed, or who own small businesses;

Places ordinary citizens in constant legal jeopardy;

Reduces consistency in enforcement;

Erodes confidence in the rule of law; and

Wastes scarce law-enforcement resources that could otherwise be devoted to preventing and punishing serious crimes against persons and property.

To address the problem, Copland and Gorodetski recommended the creation of “an independent commission charged with consolidating, clarifying, and optimizing North Carolina’s criminal statutes.”

Last year, the John Locke Foundation cited the MI report and endorsed its recommendation in a compilation of legislative suggestions entitled Agenda 2016, and we did so again this year in a Spotlight report released in March. In the Spotlight, we explained the problem in some detail:

Chapter 14 of the North Carolina General Statutes, which deals specifically with “Criminal Law,” includes over 840 sections. … Definitions of hundreds of additional crimes are sprinkled here and there throughout more than 140 other chapters of the General Statutes. Making matters worse, these and other chapters also include numerous “catchall” provisions that criminalize the rules and regulations that are promulgated by various administrative agencies, by professional licensing boards, by county and municipal governments, and even by metropolitan sewer districts. These criminalized rules and regulations do not appear in the General Statutes at all. Instead, a citizen who wants to learn about them must comb through hundreds of pages of the N.C. Administrative Code and other compilations. …

The result is patently unjust. Because there are so many of them and because they have been documented in such a haphazard fashion, it is impossible for ordinary citizens to learn about and understand all the criminal laws and criminalized regulations that govern their everyday activities. Moreover, because so many of those laws and regulations criminalize conduct that is not inherently evil and does not cause harm to any identifiable victim, ordinary citizens cannot rely on their intuitive notions of right and wrong to alert them to the fact that they may be committing a crime.

And we emphasized that, to be a successful solution, the recodification process must:

Eliminate all crimes that are obsolete, unnecessary, redundant, inconsistent, or unconstitutional, and, where appropriate, downgrade minor regulatory offenses from crimes to infractions;

Ensure that the definition of each crime is clear and complete, and that it includes an explicit statement about what level of [criminal intent], if any, is required for conviction; and

Consolidate the entire body of criminal law into a single, well organized and clearly written chapter of the General Statutes.

We were delighted, therefore, when—thanks in large part to Rep. Dennis Riddell (R, Alamance)—a provision establishing a “Criminal Code Recodification Commission” was added to HB 482 and to SB 114. Under the proposed language, “The Commission shall produce … a fully drafted, new, streamlined, comprehensive, orderly, and principled criminal code … [and] shall”:

(1) Include necessary provisions not contained in the current code, such as mental states, defenses, and definitions of offenses and key terminology.

(2) Eliminate unnecessary, inconsistent, or unlawful provisions in the current code.

(3) Revise existing language and structure to make the law easier to understand and apply.

(4) Ensure that criminal offenses and legal rules are cohesive and relate to one another in a consistent and rational manner.

(5) Incorporate within the proposed new code all major criminal offenses contained in existing law.

(6) Make recommendations regarding whether any existing offenses should be reclassified as infractions punishable only by a fine.

(7) Make recommendations regarding whether any limitations should be placed on the ability of administrative boards, agencies, local governments, or other entities to create crimes.

(8) Seek to preserve the North Carolina General Assembly’s substantive policy judgments as reflected in the existing code and legal principles established in the case law.

(9) Address any other matter deemed necessary to carry out the work of the Commission.

There is much more to the proposal, all of it excellent. When it was introduced, I described it as “an auspicious beginning” and predicted that, if enacted, “[I]t would establish North Carolina as the clear leader in criminal justice reform and make us an example for the rest of the country to follow.” Neither HB 482 nor SB 114 passed during the regular session. However, the General Assembly meets in special session later this week and again in September, and I am hopeful that it will authorize the Recodification Commission during one of those sessions.

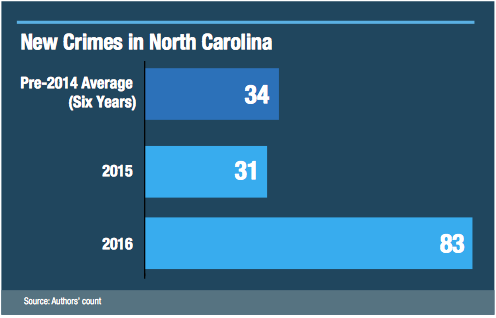

To encourage that outcome, I note that, just yesterday, the Manhattan Institute released a follow-up to the 2014 report referred to above. In “North Carolina Overcriminalization: Update 2017,” James R. Copland and Rafael Mangual describe the continued proliferation of criminal offenses during the 2015 and 2016 legislative sessions. They note, with alarm, that new crimes were created in 2016 at a rate that far exceeds the rate during the previously studied period:

And, in an even more worrisome development, they note that many of these new crimes were compiled “outside North Carolina’s criminal code”; “concern ordinary business activity”; and “grant unelected administrative authorities the effective power to add new crimes to the state’s books.” For example:

The 2016 act governing the manufacture and sale of bedding criminalized not only the provisions of that legislation but also “the rules, regulations, or standards promulgated” under it by the state’s Commissioner of Agriculture. The 2016 statute governing the conduct of those licensed to engage in the business of money transmission criminalized the violation of the federal Bank Secrecy Act, the federal Electronic Funds Transfer Act, and the violation of all “applicable State and federal laws and regulations related to the business of money transmission.”

Copland and Mangual are as enthusiastic as I am about the recodification proposal that’s currently under consideration:

As currently drafted, this legislation would charge the commission with eliminating “unnecessary, inconsistent, or unlawful provisions in the code” and placing limits on “the ability of administrative boards, agencies, local governments, or other entities to create crimes.” Also, Section (e)(1) of the draft legislation specifically mentions the absence of criminal-intent requirements in many North Carolina criminal statutes…. The North Carolina General Assembly reconvenes for a special session on August 3, 2017, and is scheduled to go into session again in September. Ideally, the legislation could be enacted this summer or fall to jump-start the commission’s efforts; if not, one hopes that the legislature will take it up when it reconvenes in January 2018.

What’s more, it’s not just the folks at the Manhattan Institute who are watching our recodification project with interest. In recent weeks, I’ve been contacted by a number of think tanks—including some based in Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Texas, and Washington, DC—all of whom have wanted to know more about North Carolina’s recodification initiative. In response, I’ve sent them copies of the various Manhattan Institute and John Locke Foundation publications referred to above along with the current legislative language.

The whole country is hoping North Carolina will take the lead on this important reform. Let’s not let them down!