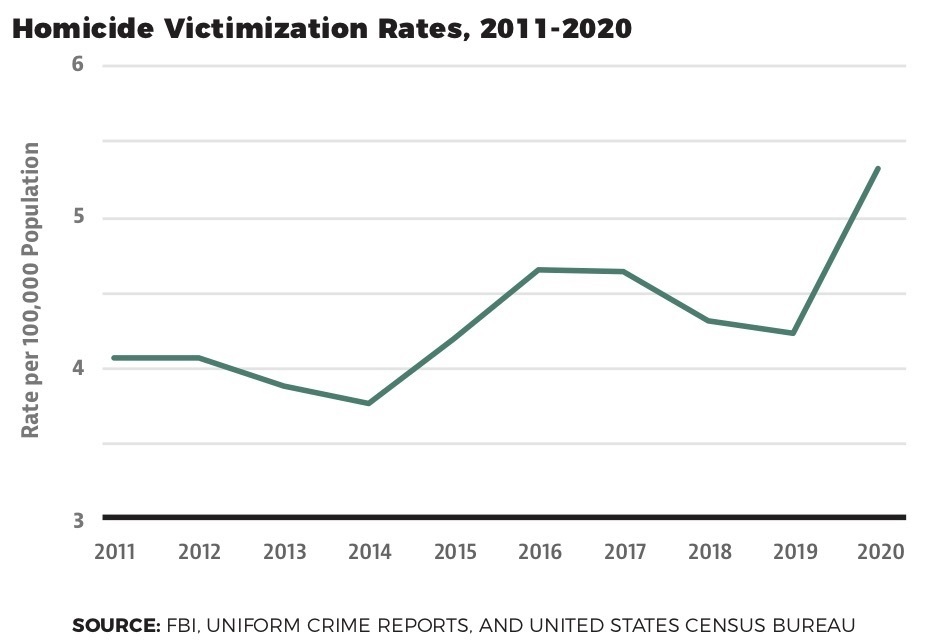

- The current spike in homicides and other violent crime has created an urgent need for more and better policing

- Unfortunately, the lingering effects of the anti-police hysteria that swept the country after the death of George Floyd may make the idea of spending more money on the police hard to sell

- Nevertheless, there are a number of reasons to think it can be done

For almost two years, the John Locke Foundation has been warning about a national spike in violent crime and calling for a response that requires more police funding. To be specific, we have been advocating what we call “intensive community policing,” i.e., the strategic deployment of large numbers of well-trained, well-managed police officers to act as peacekeepers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods.

Previous installments in this series have made the following points summarizing our position:

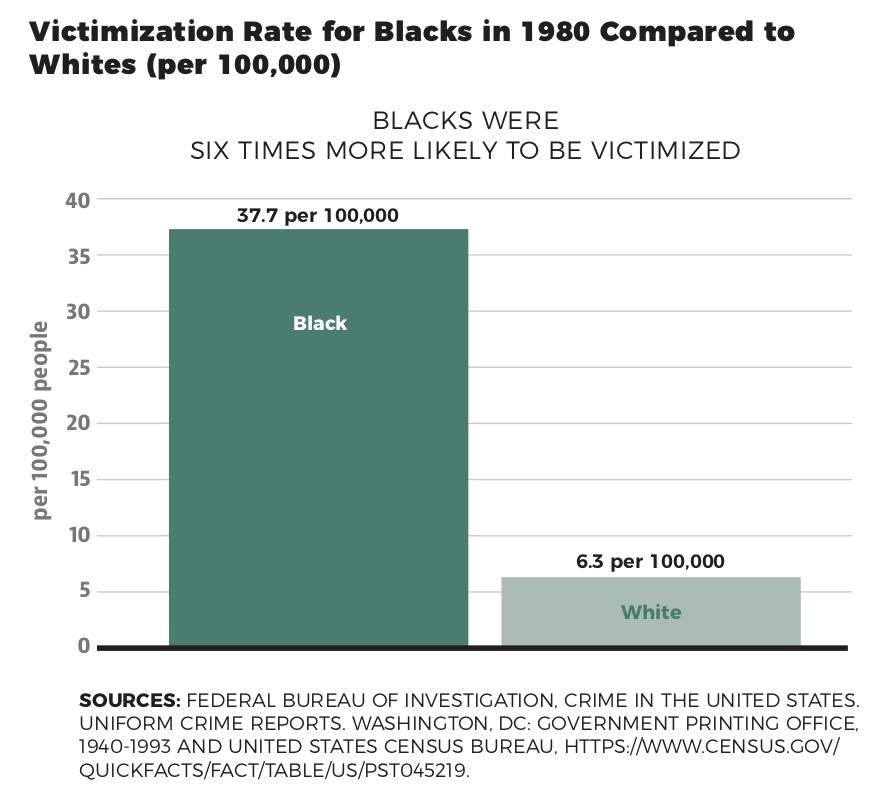

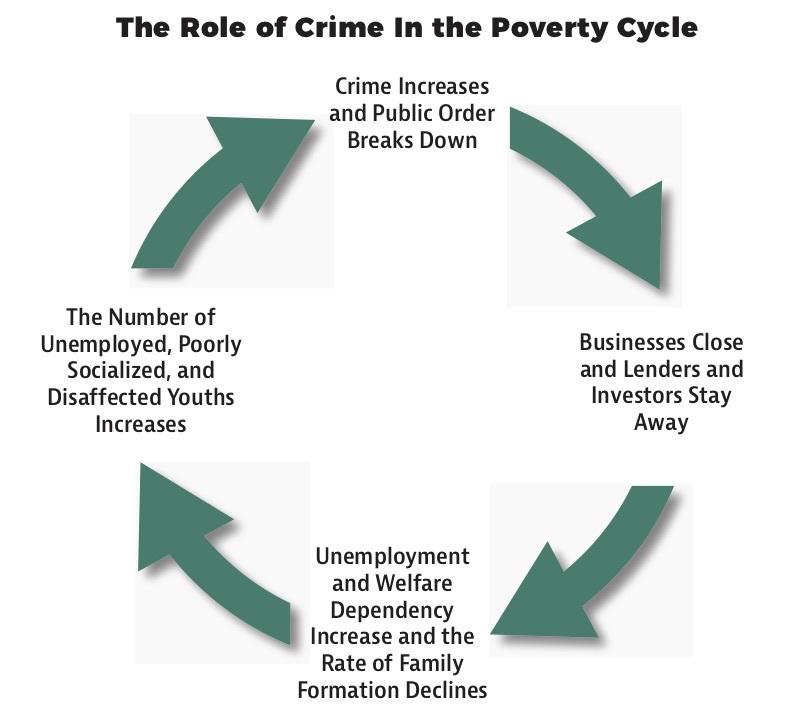

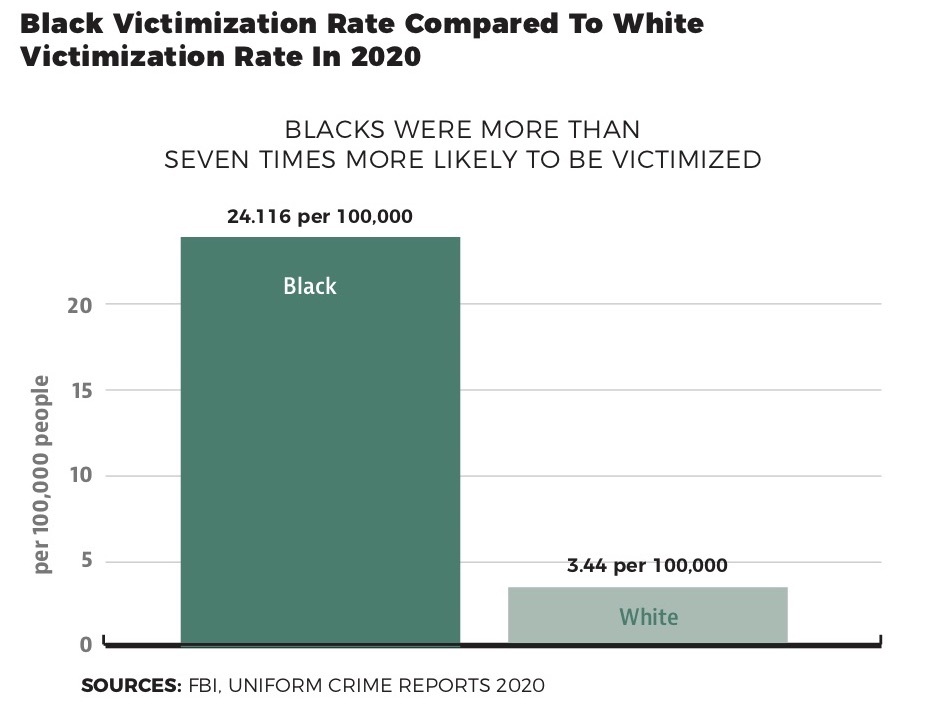

1. The crime wave that swept the country in the late 20th century was a disaster for Blacks and the poor

2. The current crime wave that began after the death of George Floyd will also be disastrous for Blacks and the poor unless it is quickly brought under control

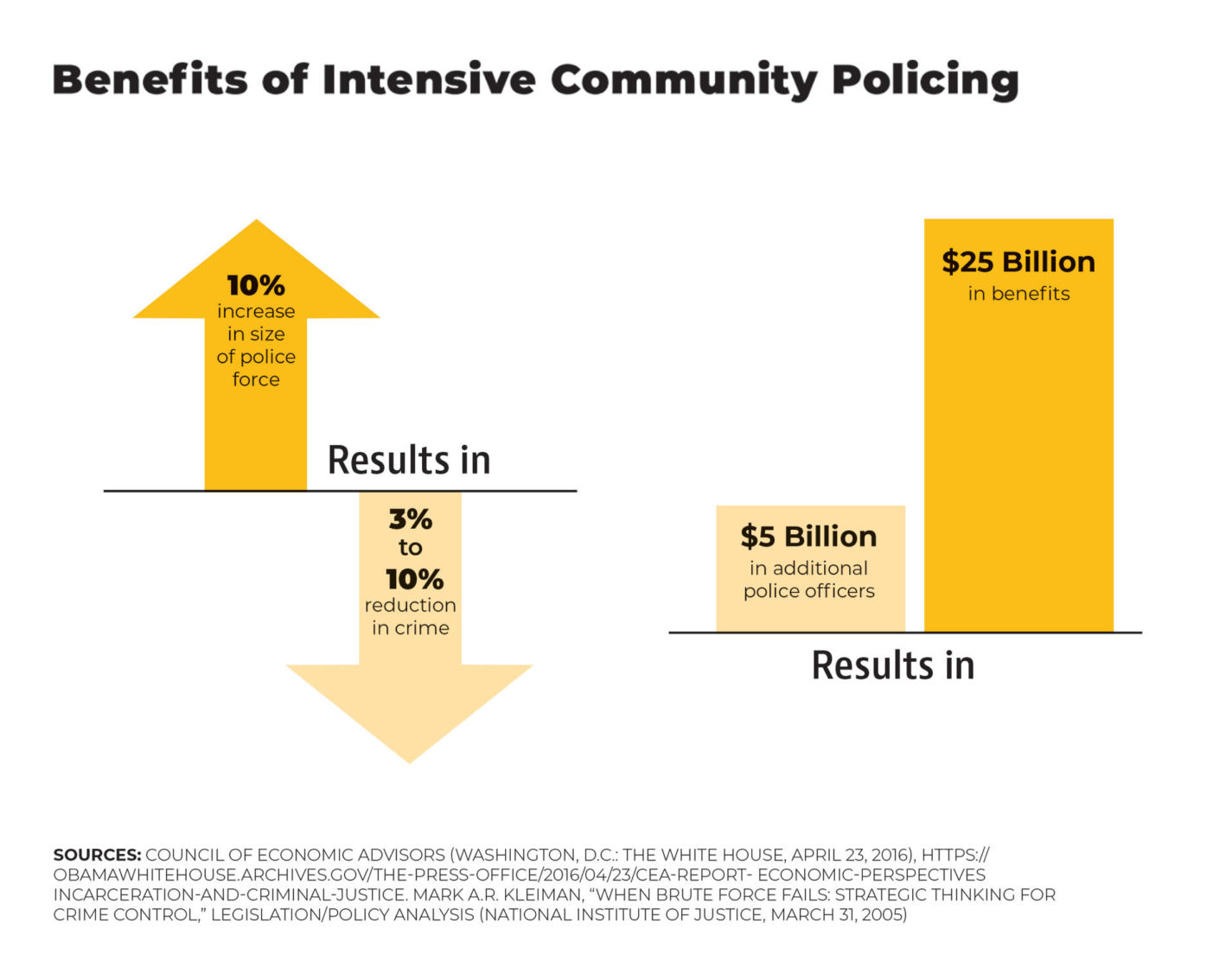

3. Research has consistently found that police presence deters criminal conduct and that the benefits that accrue from increased police presence greatly exceed the costs

For all those reasons, the best policy response to the current crime wave would appear to be obvious. We should:

- Hire more police officers

- Pay them higher salaries

- Provide them with state-of-the-art training and support

- Deploy them as “peacekeepers” in communities that suffer high levels of crime and disorder

Implementing a program of intensive community policing will be expensive, of course, and the lingering vestiges of the anti-police hysteria that swept the country after George Floyd’s death may make it hard to convince politicians and taxpayers that the costs are worth paying. Nevertheless, there are several reasons to believe it can be done.

One reason for optimism is the fact that, prior to George Floyd’s death, support for higher levels of police spending had actually been growing. See, for example, Inimai M. Chettiar’s “More Police, Managed More Effectively, Really Can Reduce Crime,” which appeared in The Atlantic in 2015; Matthew Yglesias’ “The case for hiring more police officers,” which appeared at Vox in 2019; and Megan McArdle’s “If we want better policing, we’re going to have to spend more, not less,” which appeared in the Washington Post in 2020. Floyd’s death may have temporarily made such arguments unwelcome, but it did not change the fact that the arguments themselves were sound. As time goes by, people will be increasingly willing to consider those arguments objectively and appreciate their merits.

Increased police presence will result in fewer crimes; fewer crimes will mean fewer arrests and convictions; and fewer arrests and convictions will mean lower levels of incarceration and fewer ex-offenders dealing with collateral consequences and trying to reintegrate into society.

A second reason for optimism is the existence of a large, bipartisan criminal justice reform movement. The movement existed long before Floyd’s death turned police misconduct into a national obsession, and it will continue to exist long after popular attention has moved on to other things. Many criminal justice reformers are already active supporters of community policing, and even the ones who have been focused on other kinds of reforms — things like reducing incarceration levels, mitigating the collateral effects of criminal charges and convictions, and reintegrating ex-offenders into society — should be happy to endorse intensive community policing because it complements what they are trying to do. Increased police presence will result in fewer crimes; fewer crimes will mean fewer arrests and convictions; and fewer arrests and convictions will mean lower levels of incarceration and fewer ex-offenders dealing with collateral consequences and trying to reintegrate into society.

Yet another reason for optimism is a shift in public opinion with regard to public safety that has followed the recent spike in crime. As a result of this shift, even left-leaning politicians who were recently spouting anti-police slogans now find themselves under pressure to explain how they plan to restore public order and stop the spike in homicides. Because it focuses on deterrence rather than punishment, intensive community policing offers them a way to satisfy that demand without appearing to be hypocrites. They can say, in effect, “I’m not advocating more money for the bad old type of policing that I’ve criticized in the past. I’m advocating money for something new and better.”

One last reason for optimism is the persuasive power of two indisputable facts: intensive community policing will save thousands of lives very year, and most of the lives saved will be Black lives. Given that millions of Americans of all races have embraced the spirit of the “Black Lives Matter” slogan, all that would seem to be required is to bring those facts to the attention of a sufficiently large number of people. How that might be done will be the topic of the next and final installment in this series.

For additional information see:

Black Lives Matter – Which Is Why We Need More Police Funding, Not Less

The Late 20th Century Crime Wave Was a Disaster for Blacks and the Poor

How America Ended Up Underpoliced and Overincarcerated

“Broken Windows Policing”: Good Policy, Bad Name

What Does Intensive Community Policing Entail?

Prominent leftist suddenly sees that violence is bad, but for the wrong reasonWhy Defunding the Police Is a Terrible Idea