- DHHS data show that North Carolinians with natural immunity are much less likely to contract Covid than even vaccinated individuals

- Data show the reinfection rate (a measure of the strength of natural immunity) is lower than the post-vaccination infection rate (strength of vaccination)

- The reinfection rate was likely less (possibly much less) than 0.8% while the post-vaccination infection rate was at least 1.3% (and possibly much greater)

North Carolina hospitals made national news over massive layoffs of people for not submitting to a Covid-19 vaccine. Gov. Roy Cooper and his media acolytes praise businesses that deny access to customers without proof of vaccination. The Biden administration is working up an emergency rule to force employers with 100 or more employees to require vaccination or else face crippling fines. Not done yet, the president seeks to forbid air travel to “the unvaccinated” and is piloting a way to raise massive taxes on people relegated to driving their vehicles instead.

Nevertheless there is a growing body of research showing that immunity to Covid-19 and its variants from a prior infection (natural immunity) is significantly stronger and longer-lasting than vaccine-induced immunity. If this great exercise in dreaming up all kinds of ways of depriving your friends, family, and neighbors of their livelihoods and even mundane participation in daily living is somehow justifiable in order to bring about greater societal protection to Covid, then shouldn’t natural immunity factor? Why not?

This research brief will discuss official state data on reinfections and post-vaccination infections as indicators of the relative strengths of natural immunity and vaccine-induced immunity. A following research brief will discuss the implications with regard to vaccine mandates.

Natural immunity in North Carolina

New data published by the North Carolina Department of Health and Humans Services (DHHS) show that yes, even in North Carolina, natural immunity from a prior infection is stronger than the vaccine-induced immunity.

In a new publication entitled “Historical Reinfection Data: March 1, 2020 – September 20, 2021,” DHHS announced on Oct. 4 that, owing to a change in the definition of a Covid surveillance case by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), they will begin reporting reinfections of Covid-19 as part of the daily Covid-19 case count. As DHHS explains, “The dashboard does not currently include subsequent COVID-19 infections for people who have been diagnosed with COVID-19 more than once so the change will cause an increase in the number of COVID-19 cases being reported in the state” (emphasis added).

What that means is that if someone was diagnosed with Covid, that would add to DHHS’s total case count, but if that person was diagnosed with Covid again, DHHS was not adding that person to the case count again — there was no double-counting of individuals with subsequent cases.

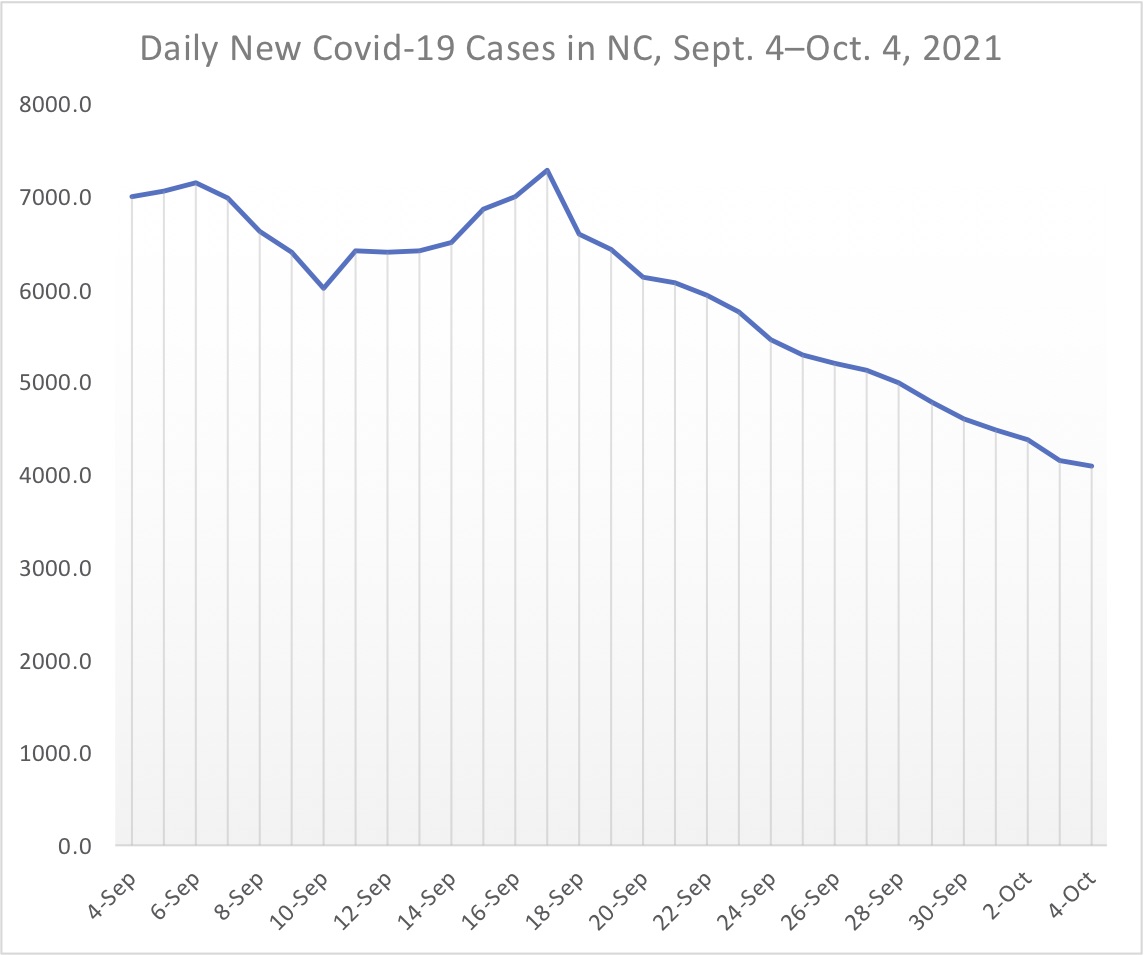

The move comes just in time, as daily new cases — the main impetus behind all fear-based Covid orders and mandates, including schools’ antiscientific mask orders against defenseless children — have been falling:

Figure 1. 7-Day Rolling Average Daily New Covid-19 Cases in NC in the Last Month

Source: DHHS

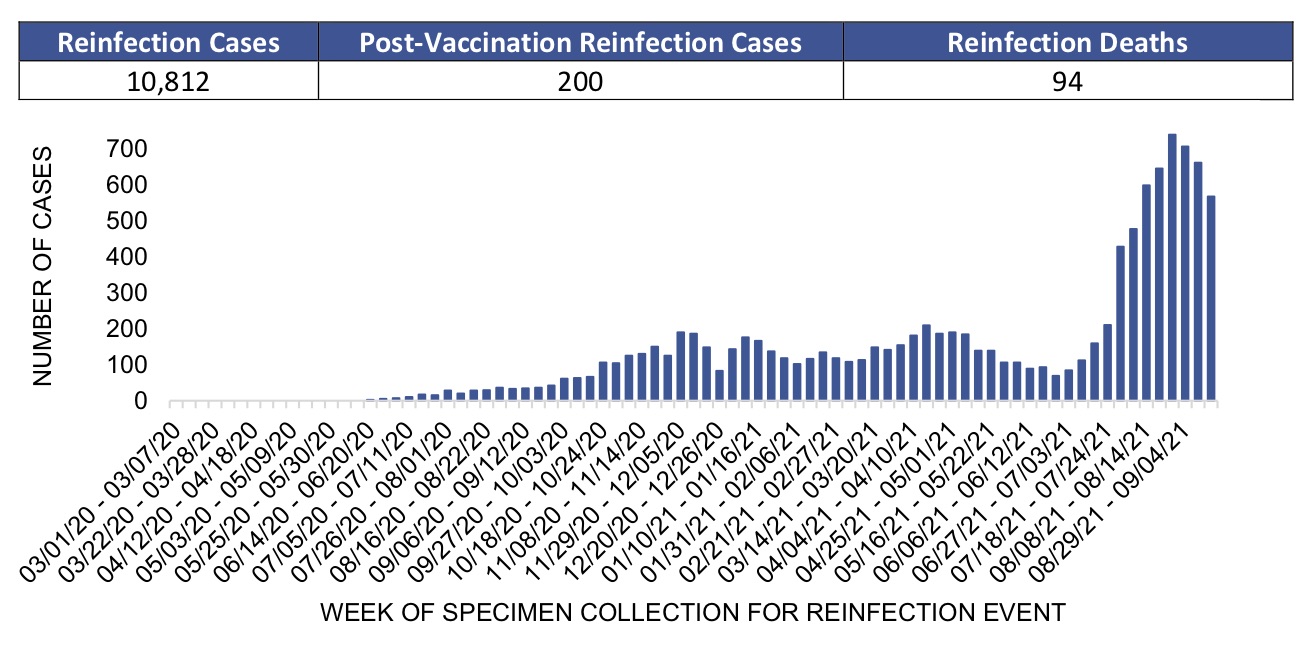

In the course of the report, DHHS gives a graph showing the previously withheld reinfection data:

Figure 2. Covid-19 Reinfections in North Carolina

Source: DHHS

The reinfection rate: an indicator of the strength of natural immunity

Here’s what those numbers also mean. Of the 1,346,316 cases reported by Sept. 20, 2021, there were 10,812 reinfection cases not included. Dividing 10,812 reinfections by the 1,346,316 people with known cases means the reinfection rate was 0.8%.

A caveat: we don’t know how many of these reinfections are actual re-infections. An earlier Fog of Covid-19 Data report discussed the large false positivity issue concerning the PCR tests used to determine the great majority of cases in North Carolina. A “reinfection” could therefore be one of three things:

- a person who has indeed suffered a second infection from Covid-19

- a person who was incorrectly diagnosed with Covid and later infected

- a person who had originally been infected with Covid and later incorrectly diagnosed

Being able to account for the latter two properly would have the effect of reducing the numerator (reinfection cases) and increasing the denominator (first-time cases), which would mean the reinfection rate was less than 0.8%.

Another caveat: the CDC readily acknowledges that there are an estimated 4.2 actual Covid infections for every reported case. Being able to account for actual infections and actual reinfections properly would increase first-time cases (the denominator) by 4.2, but it seems unlikely there would be as many unknown reinfections. This in combination with the above caveat would mean the reinfection rate was likely much less than 0.8%.

The post-vaccination infection rate: an indicator of the strength of vaccine-based immunity

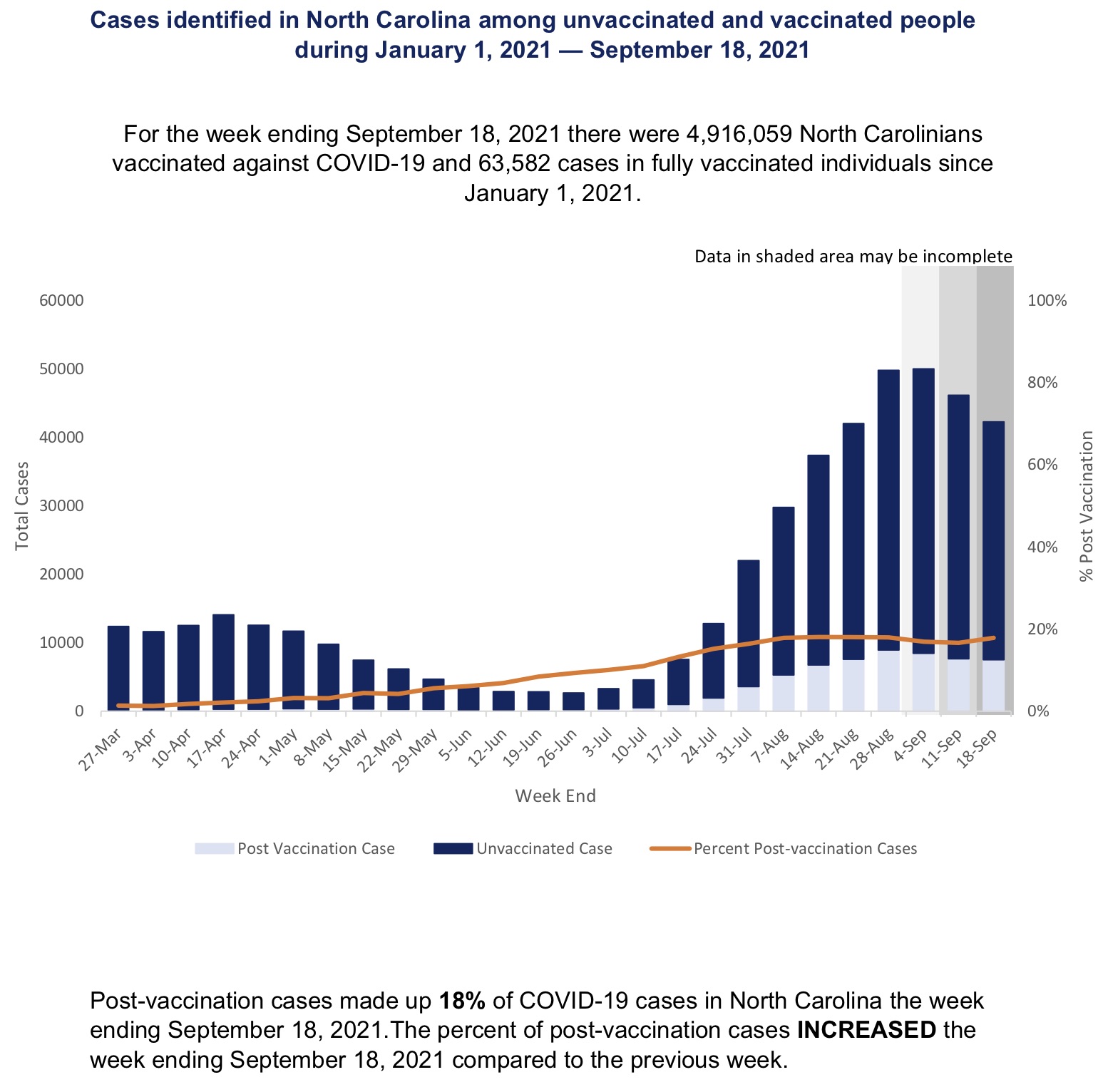

In a different publication, the most recent “Respiratory Surveillance” report (covering September 19–25, 2021), DHHS gives information on post-vaccination cases, which currently comprise 18% of current cases in North Carolina:

Figure 3. Covid-19 Post-Vaccination Cases in NC

Source: DHHS

Those data are instructive. Note that there were over three and a half times more people vaccinated against Covid by September 18 than there were cases of Covid by September 20: 4,916,059 vaccinations vs. 1,346,316 cases. But there were nearly six times more post-vaccination cases than reinfections: 63,582 post-vaccination infections vs. 10,812 reinfections.

Dividing 63,582 post-vaccination infections by the 4,916,059 people vaccinated means the post-vaccination infection rate was 1.3%.

A caveat: DHHS has a very specific definition for a “post-vaccination case.” The way DHHS defines post-vaccination is not how the general public would define post-vaccination. It isn’t “Did you get Covid even after you got ‘the jab’?”

Instead, it’s “Did you get Covid beyond two weeks after you completed both ‘jabs’ and you had gone a month and half without a positive test result?” Here it that definition:

Figure 4. How DHHS Defines a “Post-Vaccination Case”

Source: DHHS

What that definitional technicality means is that there is an unknown number of Covid cases in North Carolina that have occurred either (a) within two weeks of completing a full course of Covid vaccinations or (b) after the first injection when someone was partially vaccinated (no small matter; DHHS considered partial vaccination very important, as attested by the fact that the governor’s standard for reopening was at least two-thirds of adults partially vaccinated). In regular conversation, those would be post-vaccination cases, but not according to DHHS.

This would mean some people testing positive for Covid did so after being fully vaccinated, but they are considered “unvaccinated” by DHHS if they did so within 14 days of receiving their second shot. Some contracted Covid before getting their second shot. Being able to account for those individuals properly would mean the post-vaccination infection rate was actually much greater than 1.3%.

Recap

Using data from DHHS, this research brief showed the following:

- North Carolinians with natural immunity are much less likely to contract Covid than even vaccinated individuals.

- The initial findings are that the reinfection rate was 0.8% while the post-vaccination infection rate was 1.3% — but that is without consideration of the known problem of PCR-based false positives, how many infections there are to known cases, and also how DHHS defines away post-vaccination cases that occurred either within two weeks of vaccination or after the first injection.

- The reinfection rate was therefore likely much lower than 0.8% while the post-vaccination infection rate was likely much greater than 1.3%.

A follow-up to this brief will discuss why these findings mean that Covid-19 vaccination mandates must end immediately.