Avik Roy reminds Forbes readers that much of the credit for recent improvement in the American economy ought to go to a policy President Obama opposed.

In January, in his annual State of the Union address, President Obama bragged that “our economy is growing and creating jobs at the fastest pace since 1999.” It’s great news, to be sure. But according to a new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research, the recent improvement in the labor market may be due to a policy change that Obama adamantly opposed: ending extended unemployment benefits.

President Obama pushed for the continuation–and expansion–of extended benefits throughout his first term.

Finally, after years of slack labor markets, in July 2013 the unemployment rate fell below 7.5%. In December 2013 the House of Representatives—now controlled by Republicans—allowed the benefit extension to expire, arguing that the crisis of the Great Recession had passed.

Obama blasted the House’s decision: “For many of their constituents who are unemployed through no fault of their own, [Republicans] will leave them with no income at all. And denying families that security is just plain cruel.” The President’s Council of Economic Advisers and the Department of Labor predicted that the expiration of extended benefits would reduce employment by 240,000; the Congressional Budget Office estimated that employment would be lower by 200,000.

But the predicted apocalypse never occurred. Instead, the unemployment rate dropped from 6.7% in December 2013 to 5.6% a year later, despite a drop in the growth of aggregate productivity. The new NBER paper—authored by economists at the University of Oslo, Stockholm University and the University of Pennsylvania—finds a strong relationship between the drop in unemployment benefits and the rise in employment.

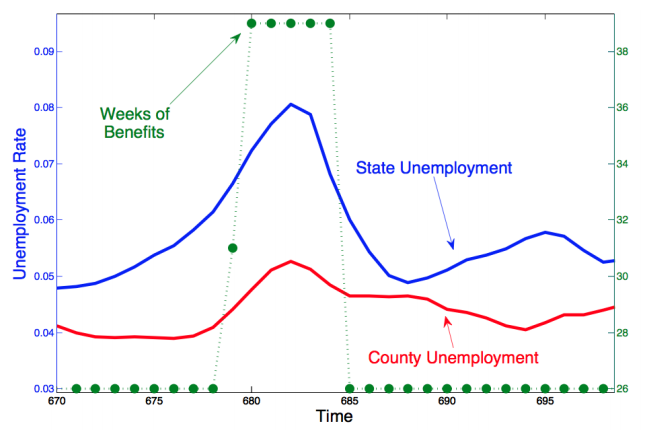

The authors compared neighboring counties in adjacent states, and found that states that had the shortest duration of unemployment benefits experienced the strongest labor market recovery. “A 1% drop in benefit duration leads to a statistically significant increase of employment. 1.8 million jobs were created in 2014 due to the benefit cut.” Those 1.8 million jobs represent 1.2% of the U.S. labor force: correlating quite closely to the drop in unemployment over the past year.

The new paper is a follow-up to earlier research from the same authors about the labor market in North Carolina. When North Carolina shut down its extended unemployment benefits program in July 2013, “robust employment growth” followed.