Bjorn Lomborg recently wrote about green energy poverty in The Wall Street Journal. He warned about how climate-change policies were producing higher energy costs that fall disproportionately on the poor.

The underlying issue is that everyone, rich or poor, needs energy. It is a basic human need, so anything that makes it more expensive will disproportionately harm the poor more. (And anything that makes it less costly will disproportionately help the poor.)

Lomborg writes:

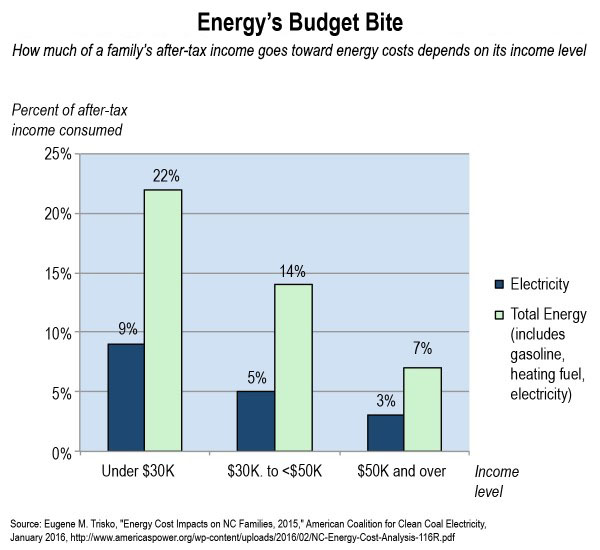

Economists consider households energy poor if they spend 10% of their income to cover energy costs. A recent report from the International Energy Agency shows that more than 30 million Americans live in households that are energy poor—a number that is significantly increased by climate policies that require Americans to consume expensive green energy from subsidized solar panels and wind turbines.

Last year, for the first time, the International Energy Agency tried to calculate the global scale of this problem. The IEA estimates that in the world’s rich countries—those that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development—200 million people are in energy poverty. That includes 1 in 10 Americans, although the IEA notes that the highest estimates for the U.S. approach 1 in 4.

People of modest means spend a significantly higher share of their income paying for their energy needs. One careful study of energy usage in North Carolina found that a lower-income family might spend more than 20% of its income on energy. Among people with incomes below 50% of the federal poverty line, energy costs regularly consumed more than a third of their budgets.

Here is how the problem is exacerbated. While poor and rich alike need energy, the rich are far more able to access efficient energy.

It was for this aspect of energy poverty that I wrote against the solar rebate program portion of last year’s House Bill 589 (see Section VIII).

As I told Carolina Journal:

Jon Sanders, John Locke Foundation director of regulatory studies, said utilities fare well under the rebate program because the REPS law includes a provision (known as the “green source rider”) letting the companies recoup the cost of the rebates and higher energy prices.

“Guess what that means about who pays for it? Customers who don’t participate — or can’t, such as people who rent, who live in apartments, or are in mobile homes. It’s another case of forcing poor people to subsidize the choices of the rich,” Sanders said.

“This law basically subsidizes a specific consumer choice for a specific product by consumers who wouldn’t make that choice for themselves. There are many terms for such a thing, but ‘sustainable practice’ is not among them,” Sanders said.

Unsettingly energy poverty facts

This week CityLab has a report about this imbalance of energy efficiency disproportionately benefits the rich, leaving the poor behind. Here are facts from the report:

- “Low-income Americans are more likely to live in housing that wastes energy, which saddles them with disproportionately high energy costs.”

- Some people in energy poverty are “paying utility bills that are as much as their mortgage.” (Cf. this story from Eastern N.C. of poor people paying $316 to $849 on electricity.)

- “[L]ow-income, black, and Hispanic communities spend a much higher share of their income on energy.”

- “Utility bills are the primary reason why people resort to payday loans.” (Cf. how “advocates for the poor” take even those options away, leaving the poor sometimes with the dangerous choice between going without electricity or going to a loan shark.)

- “Living in under-heated homes puts occupants at a higher risk of respiratory problems, heart disease, arthritis, and rheumatism.”

- “[L]ow-end housing is significantly less energy-efficient than other housing stock. People with less money aren’t just paying a greater proportion of their income for energy—they’re paying more per square foot.”

- Energy-efficiency and home weatherization programs are often inaccessible to the poor because they require upfront investment and don’t yield costs savings until years later.

- Even government programs to upgrade public housing and offer energy-efficiency tax credits don’t help a major category of poor ratepayers: renters.

And, of course, rebates for special energy programs paid for by riders on all ratepayers essentially make poor ratepayers and renters pay for programs wealthy ratepayers use, but they can’t.