Last year I noted how frequently the General Assembly fields requests to bring more occupations under state licensing. At the same time, I observed several overarching reasons why North Carolina should be freeing more occupations from licensing, rather than bringing more in. Licensing is the most extreme form of state regulation of a legal industry.

As the John Locke Foundation’s policy position on occupational licensing explains,

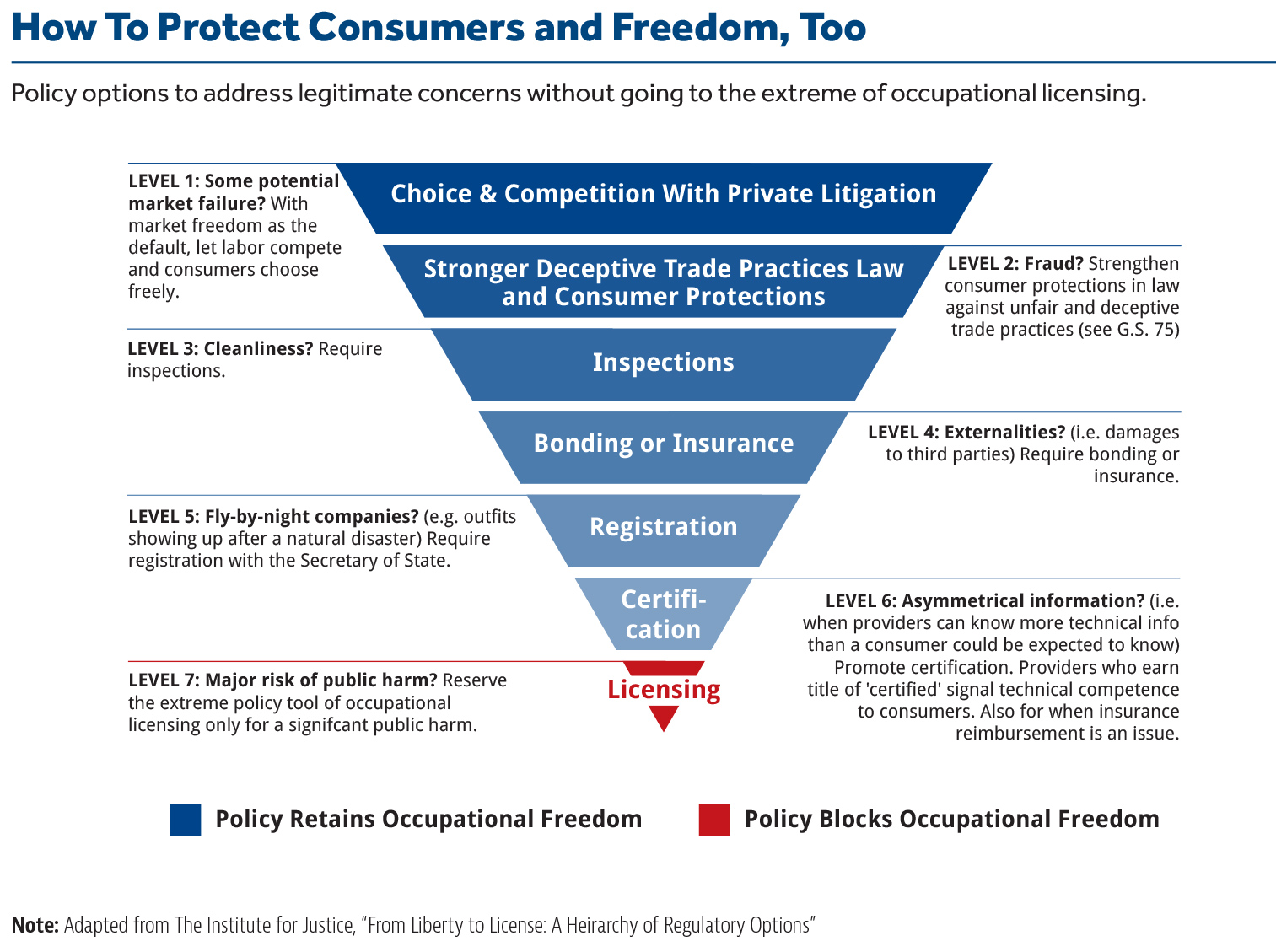

- The state’s default policy option should be occupational freedom, trusting competitive forces, consumers, information providers, and the courts. If legitimate, serious safety concerns are identified, policymakers have several policy options other than licensing that still preserve occupational freedom. The keys are to match the regulation to the concern and then go no further.

- Options include greater powers to the attorney general and the deceptive trade practices act, inspections, bonding, registration, and recognition of certification. Unlike licensing, none of those policy options would preclude North Carolinians from enjoying their self-evident right to the enjoyment of their own labor.

The issue of food handlers offers a good case study. Here is an occupation that might well have tempted legislators to bring it under state licensing in past years, such as 1967-2010, when new occupational licenses were being created at a rate of about one every seven months. Since Republicans have gained control of the General Assembly in 2011, however, there’s been a pause on creating new licenses.

The issue, in brief, is this: fruit and vegetable farmers have a short time window in which to deliver unspoiled crops for sale at grocery stores. They contract with food handlers to perform this service. Food handlers’ dishonesty, negligence, or otherwise failure to perform this service adequately results in an economic loss to the farmers. Grocers won’t select spoiled wares and will offer less than expected market prices for the rest. Dishonest handlers can issue farmers improper payments or even refuse to pay them altogether.

Under current law, handlers must get a permit from the Commissioner of Agriculture and be bonded at least to $10,000 before being able to contract with a farmer. By the sound of it, this arrangement lacks strong enough disincentives against poor service by handlers. What is proposed in Senate Bill 711 is a different level of state oversight that seeks to address the concern with the industry and go no further.

Matching the regulation to the concern

The proposed change would require handlers to register with the Commissioner of Agriculture at no charge but be subject to fines of at least $100 per violation of the Board of Agriculture’s rules pertaining to food handlers. Food handlers would have to give the agriculture commissioner their name, primary place of business, kinds of fruits and vegetables they handle, and annual volume of their business in dollars.

Registration is the policy alternative to licensing when the concern is shady service providers taking advantage of people.

An earlier version of the legislation would have retained bonding at stipulated levels and required handlers to obtain a privilege license from the Board of Agriculture at a steep cost of $500 for new licenses, renewed annually at $250. Georgia and Florida, for example, both have privilege licenses with surety bonds for food handlers. But for North Carolina, the fee would have been prohibitively high.

A good sign for North Carolina

The legislature’s willingness to probe and seek a proper remedy to an issue in industry without straying into overregulation, let alone the extreme form of occupational licensing, is a good sign for North Carolina and is to be commended.