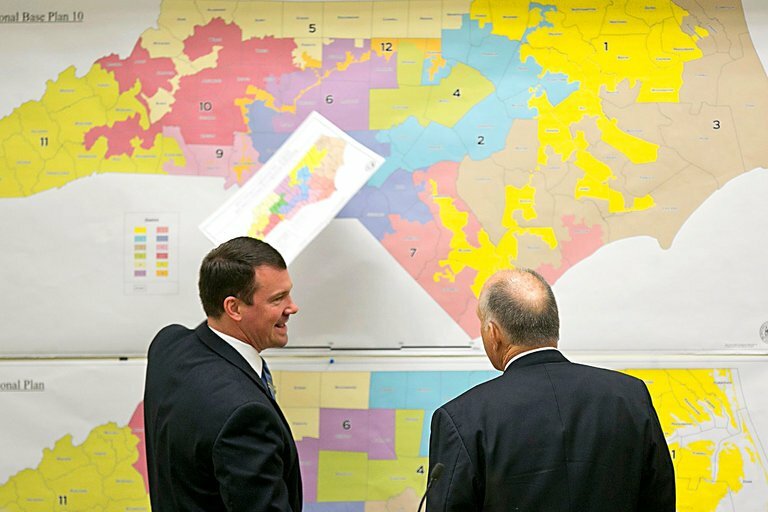

North Carolina has been embroiled in a decades-long redistricting saga since the late twentieth century. After each new map is drawn, a slew of litigation ensues that takes up significant time and resources. Many have proposed changes to the rules for redistricting to prevent partisan gerrymandering, but in a recent research brief, JLF’s Mike Schietzelt asks whether or not new rules will make a lasting impact. Schietzelt writes:

[When] new maps are invariably challenged with a surge of litigation in state and federal courts… challengers typically claiming that the map-drawers have improperly considered race or partisan advantage.

And with each round of litigation, courts craft new (and often opaque) standards. Or they attempt to make sense of previously crafted (and often opaque) standards. Or they punt on the issue altogether. Rarely do courts resolve even the most basic legal issues in a lasting way. After decades of litigation, the redistricting waters are muddier than ever and getting worse. So symposium panelists, and many others, have reasonably concluded that we need clearer rules.

But that conclusion has a fundamental flaw: crystal-clear rules mean nothing when they are read inconsistently. The rules themselves aren’t the problem. The courts are.

Schietzelt illustrates the court’s flip-flopping using partisan gerrymandering as an example:

[In 2015,] the Supreme Court of North Carolina [concluded] in Dickson v. Rucho, 367 N.C. 542, (2014)[,] “The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized that compliance with federal law, incumbency protection, and partisan advantage are all legitimate governmental interests.” And when the case came back before the Supreme Court of North Carolina a year later, the Court said exactly the same thing…

But in 2019, the three-judge panel in Common Cause v. Lewis threw that settled rule out the window.

The Common Cause panel found, for the first time in history, that “extreme” partisan gerrymandering violated the state constitution. The key provision in that case, according to the panel, was the “Free Elections clause” in Article I, Section 10, which reads, “All elections shall be free.”

…This is a truly remarkable reversal. In 2015, partisan advantage was a “legitimate governmental interest” in drawing maps. In 2019, without any changes to the underlying law, the practice became illegal.

This inconsistency in adhering to precedent is troublesome to Schietzelt. He writes:

The courts’ willingness to completely reverse course on this issue is troubling. With all due respect to proponents of redistricting reform, new rules will not rein in a judiciary that frequently moves the target and occasionally reverses course. New rules will only provide new battlegrounds for endless litigation.

And more litigation is the absolute last thing we need.

Read the full brief here. Keep up with North Carolina’s redistricting saga here.