A new study out of Germany criticizes the European Union for treating electric vehicles (EVs) as having “zero emissions” when, all things considered, they provide more air pollution than conventional vehicles.

It’s not just European governments who need to factor in these considerations. North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper has publicly suggested that 80,000 more EVs in North Carolina would mitigate hurricanes. Incentivizing state adoption of EVs is a major portion of his plan to alter the world’s climate by Executive Order. (I don’t mean for that to sound like something out of a comic book, but in the words of Emperor Joseph II, “Well, there it is.”)

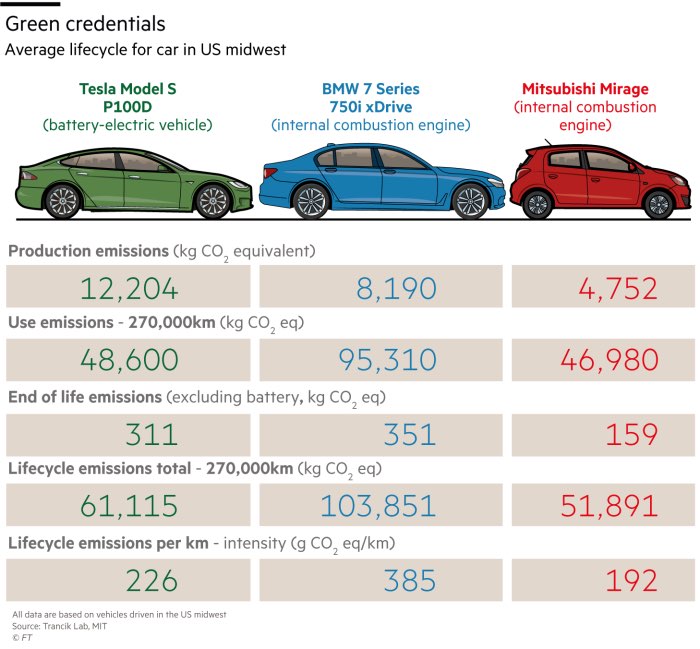

The zero-emissions case doesn’t account for emissions in the manufacture and recharging of the EVs. Mining and processing the materials used for the batteries is notoriously emissions-heavy. Recharging the EVs is more reliant on electricity generated from fossil-fuel sources because the timing — generally at peak evening time to overnight — is especially unsuited to electricity generated from renewable sources.

As reported by Brussels Times:

When CO2 emissions linked to the production of batteries and the German energy mix – in which coal still plays an important role – are taken into consideration, electric vehicles emit 11% to 28% more than their diesel counterparts, according to the study, presented on Wednesday at the Ifo Institute in Munich.

Mining and processing the lithium, cobalt and manganese used for batteries consume a great deal of energy. A Tesla Model 3 battery, for example, represents between 11 and 15 tonnes of CO2. Given a lifetime of 10 years and an annual travel distance of 15,000 kilometres, this translates into 73 to 98 grams of CO2 per kilometre, scientists Christoph Buchal, Hans-Dieter Karl and Hans-Werner Sinn noted in their study.

The CO2 given off to produce the electricity that powers such vehicles also needs to be factored in, they say.

When all these factors are considered, each Tesla emits 156 to 180 grams of CO2 per kilometre, which is more than a comparable diesel vehicle produced by the German company Mercedes, for example.

The study finds other fuel mixes provided lower emissions than EVs. This being the case, they argue that the government should “treat all technologies equally.”

As previously discussed here, recent research from MIT substantiated earlier research out of Norway on the problem of greater lifecycle emissions from EVs over some conventional vehicles.

In short, the picture on EVs isn’t as clear as Cooper et al. pretend it to be, and it certainly doesn’t come close to supporting the “zero-emissions” rhetoric (let alone the pluperfect foolishness of thinking more EVs would mitigate hurricanes).

The moral of the story

Once again, we see governments forcing policies that produce the opposite results from what they’re intended to produce, while markets independently outdo the governments’ intended results in seeking greater appeals to consumer interests.

So once again the lesson to draw, as I wrote then, is “Let consumers choose according to their own perception of their needs and wants.”