On Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, a case that will determine whether Colorado and other states can compel bakers to make custom wedding cakes for same-sex marriages. It was a fascinating discussion that focused on the question of whether the First Amendment’s free speech and religious liberty clauses apply to wedding cake makers and other creative artisans. I’ll provide some highlights below, but, first, I’ll explain how that question came to be before the court.

In 2012, when Charlie Craig and David Mullins decided to get married, same-sex marriages were illegal in Colorado. They, therefore, made plans to marry in Massachusetts, where same-sex marriage had recently been legalized, and then return to Colorado to celebrate the happy event with a formal reception for family and friends.

Having heard good things about Masterpiece Cakeshop, they visited the shop to discuss the design of a cake for the reception. When they explained what they wanted, however, the owner, Jack Phillips, regretfully told them that, while he’d be happy to sell them a standard cake any other baked goods off the self, he was unwilling to make a custom cake to commemorate their marriage because doing so would violate his Christian beliefs.

Craig and Mullins had no trouble obtaining a cake from another baker. Nevertheless, they chose to punish Phillips by filing a complaint with the Colorado Civil Rights Commission. The Colorado Anti-Discrimination Act includes a “public accommodations” provision that prohibits businesses from discriminating on the basis of race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation. Craig and Mullens claimed Phillips had discriminated against them because they were gay.

The Commission agreed. It ordered Phillips to provide cakes to same-sex marriages in the future, and it also ordered him to “change … company policies, provide ‘comprehensive staff training’ … and provide quarterly reports for the next two years regarding steps … taken to come into compliance.”

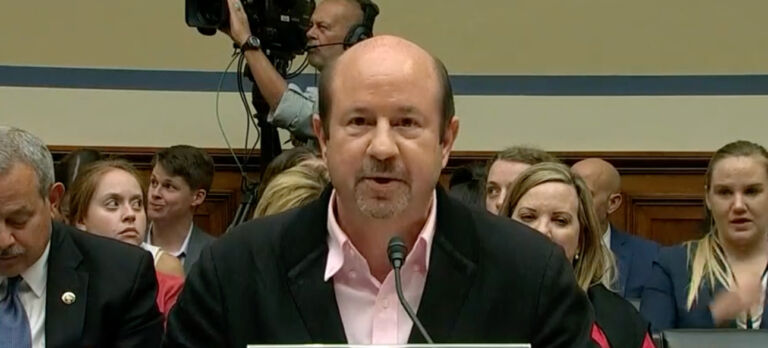

Rather than comply with that order, and violate his religious principles, Phillips chose to stop making wedding cakes altogether, even though wedding cakes had constituted almost half of his business. He also sued the Commission under the freedom of speech and the free exercise of religion clauses of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. His suit eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, and on Tuesday Phillips’ lawyers and the lawyers representing the Colorado Civil Rights Commission presented their arguments to and responded to questions from the court.

As so often happens in civil rights cases, the Court appears to be evenly divided, with Justice Kennedy holding the swing vote. If that’s true, it puts Kennedy in an interestingly conflicted position. On the one hand, he’s generally considered to be “the foremost defender of free-speech principles on the modern Court;” on the other, he wrote the Court’s 2015 decision holding that same-sex couples have a Constitutional right to marry.

For what it’s worth, journalists on both sides of the issue seem to think that the comments Kennedy made on Tuesday suggest he will probably side with Mr. Phillips. (See here, here, here, and here.) I agree, and I’ll close with a few examples.

About mid-way through the argument, Justice Kennedy initiated a long discussion of whether Colorado’s anti-discrimination law, as applied by the Colorado Civil Rights Commission, does enough to accommodate sincerely held religious beliefs. He pointed out that there was evidence to suggest that at least one commissioner was actively hostile towards religion. Justice Alito elaborated by describing several cases that came before the Commission in which bakers were asked to make cakes with messages that expressed traditional Judeo-Christian opposition to same-sex marriage:

There were bakers who said no, we won’t do that because it is offensive. And the Commission said: That’s Okay. It’s okay for a baker who supports same-sex marriage to refuse to create a cake with a message that is opposed to same-sex marriage. But when the tables are turned and you have the baker who opposes same-sex marriage, that baker may be compelled to create a cake that expresses approval of same-sex marriage. Commissioner Hess says freedom of religion used to justify discrimination is a despicable piece of rhetoric.

The justices, both liberal and conservative, went on to hammer the Commission’s attorney with many hard questions regarding the Commission’s unwillingness to accommodate religious belief, and Justice Kennedy summed up their concerns by saying:

Counselor, tolerance is essential in a free society. And tolerance is most meaningful when it’s mutual. It seems to me that the state in its position here has been neither tolerant nor respectful of Mr. Phillips’ religious beliefs.

Later in the transcript, Justice Gorsuch noted that the Commission required Mr. Phillips to provide “comprehensive training to his staff,” and asked, “Why isn’t that compelled speech?” When the Commission’s attorney tried to defend the training requirement, Justice Kennedy exclaimed:

Part of that speech is that state law, in this case, supersedes our religious beliefs, and he has to teach that to his family. He has to speak about that to his family. … His family who are the employees.

I’ll end with one final example. Late in the transcript, Kennedy raised an issue that could prove decisive—did Phillips refuse to make a cake for Craig and Mullins because they are gay, or did he refuse because they wanted to use it to commemorate a same-sex marriage? Here’s what he said:

Well, but this whole concept of identity is a slightly — suppose hesays: Look, I have nothing against – against gay people. He says but I just don’t think they should have a marriage because that’s contrary to my beliefs. … It’s not their identity; it’s what they’re doing. … I think it’s – your identity thing is just too facile.

Does any of this tell us for sure how the Court will resolve the Masterpiece Cakeshop cases? Of course not. But it does give us some interesting insight into how some of the justices, and Justice Kennedy in particular, are thinking about the case.