- Instead of ramping up police presence in high-crime neighborhoods, America responded to the late 20th century crime wave by ramping up incarceration levels instead

- The focus on punishment rather than deterrence left America significantly underpoliced, and we have remained underpoliced ever since

- The economic and social costs of the punitive approach were enormous, and most of the social costs were borne by poor and Black communities that had already been harmed the most by the crime wave

The previous installment in this series described the disastrous effect the late 20th century crime wave had on Black and poor Americans. As one would have expected, governments at all levels responded to the crime wave by allocating more money for crime control. Unfortunately, the way that money was allocated had the effect of making things even worse for Blacks and the poor.

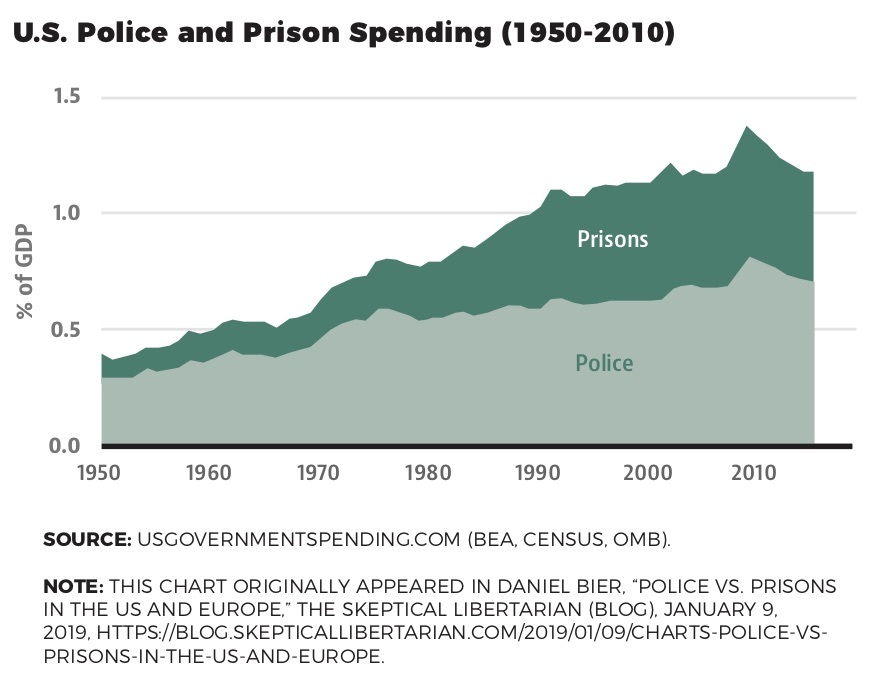

While some of the increased spending was used to hire and deploy more police officers, most of it was used instead to construct and operate more prisons. It is not altogether clear why punishment was made such a high priority. The widespread belief that the leniency of soft-on-crime judges had caused the crime wave probably had something to do with it, as did a frightened and resentful populace’s desire for retribution. The musings of an economic theorist may have also played a role. Regardless of the reason, the shift in emphasis was a marked departure from America’s past practice, and it remains an anomaly in international terms.

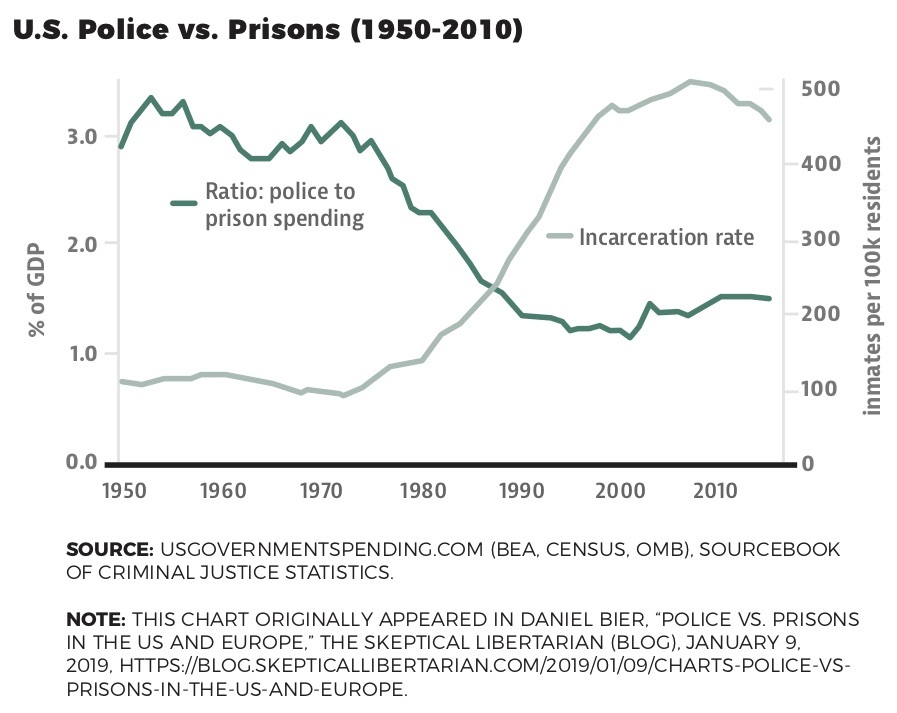

In a recent blog post, libertarian journalist and editor Daniel Bier documented the change in focus. As spending on crime control increased from about 0.8% of GDP in the 1950s to about 1.2% in the 2000s, Bier noted, there was “a relative shift of resources away from police and towards prisons.” Quantifying that shift, he wrote:

From 1950-1975, the ratio of spending on police vs. prisons stayed around 3 to 1 — that is, for every $1 spent on prisons, the US spent $3 on police. But as the US incarceration rate skyrocketed, the ratio plunged to a low of 1.17 to 1, before creeping back to 1.5 to 1 as prison populations leveled off. In 2015, the US spent just $1.50 on police for every $1 on prisons.

Bier also noted that, while European countries spend about the same percent of GDP on crime control as the United States, they allocate the money very differently:

Over the last decade (2007-2016), the US spent an average of 0.75% of GDP on police and 0.5% on prisons — a ratio of 1.5 to 1. The EU (as currently composed) spent an average of 1% on police and 0.2% on prisons — a ratio of 5 to 1.

While Bier didn’t say so explicitly, it is worth noting the implication that Europeans actually spend a higher percentage of their GDP on policing than we do here in the U.S.

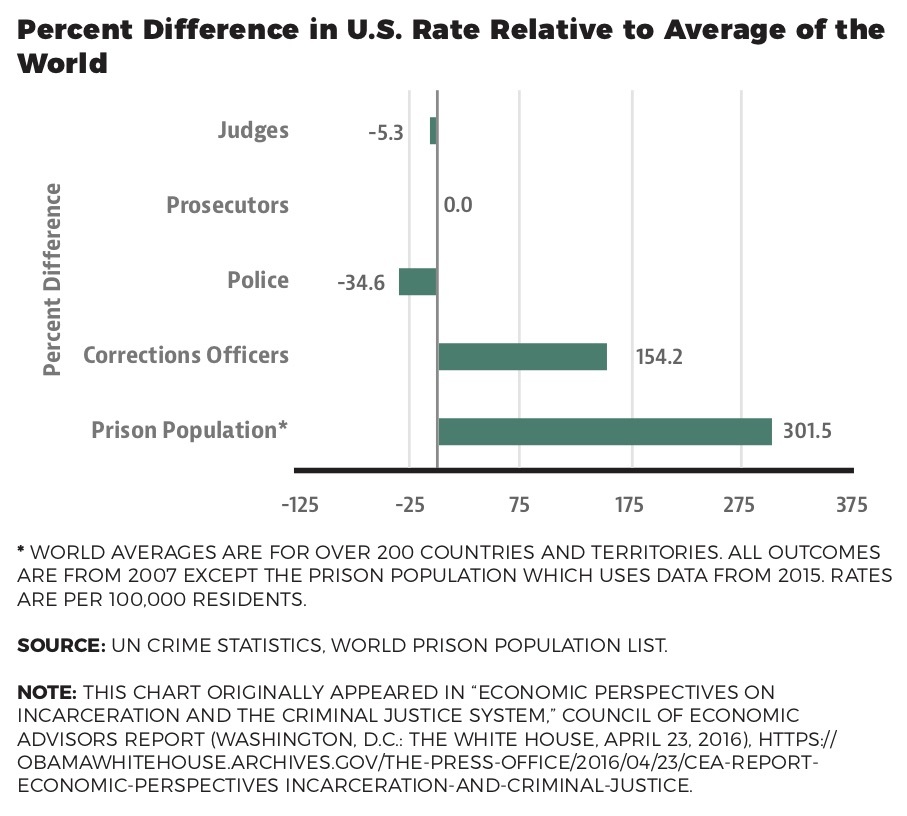

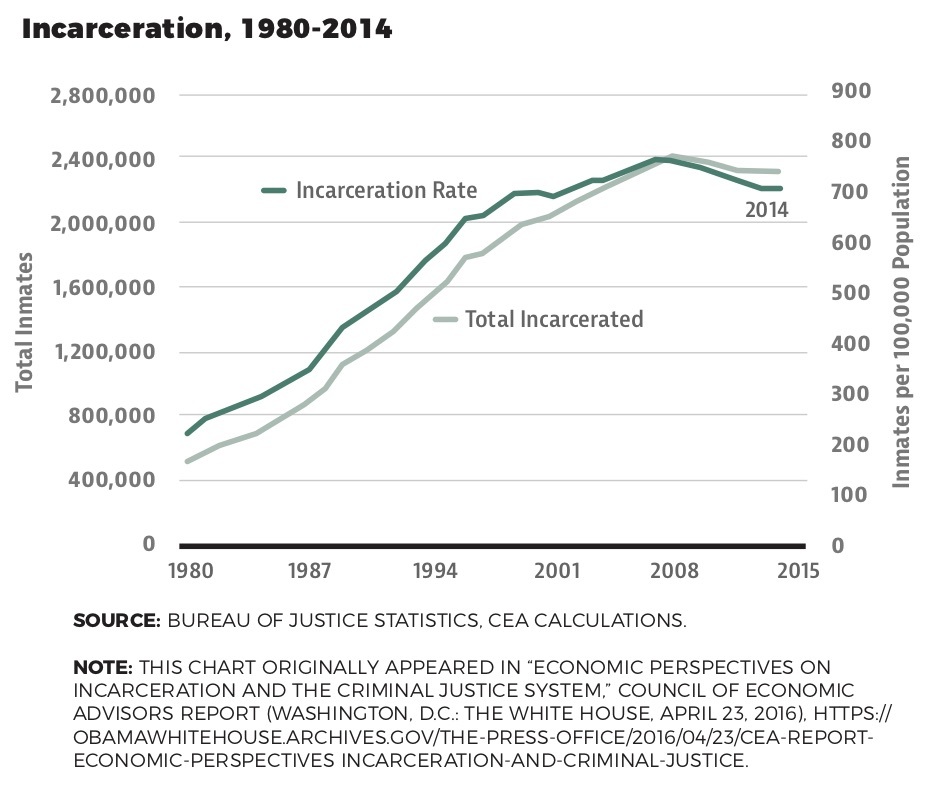

What’s more, we don’t just lag behind other countries in terms of police spending; we also lag in terms of police hiring and deployment. In 2016, the Obama administration released a report called “Economic Perspectives on Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System,” which included this chart:

Commenting on the chart, the report noted that during the relevant period the United States simultaneously had “the largest prison population in the world and … employed over 30 percent fewer police officers per capita than other countries.”

Commenting on the chart, the report noted that during the relevant period the United States simultaneously had “the largest prison population in the world and … employed over 30 percent fewer police officers per capita than other countries.”

As that chart illustrates, the shift from policing to punishment resulted in an increase in the number of incarcerated Americans that was extraordinary, not just in comparison with other countries, but in comparison with past practice in the United States itself.

While the extent to which mass incarceration helped bring about the eventual decline in crime rates is contested, it almost certainly had at least a modest deterrent effect. The costs of achieving that modest level of deterrence, however, were extremely high. It required an enormous increase in public funding, as the preceding charts imply, and it added considerably to the woes of the poor and Black communities that were already carrying so much of the burden of the crime wave. One could plausibly argue that if those funds had instead been deployed toward increasing community policing, the payoff in decreased crime would have been far more significant.

While the extent to which mass incarceration helped bring about the eventual decline in crime rates is contested, it almost certainly had at least a modest deterrent effect. The costs of achieving that modest level of deterrence, however, were extremely high. It required an enormous increase in public funding, as the preceding charts imply, and it added considerably to the woes of the poor and Black communities that were already carrying so much of the burden of the crime wave. One could plausibly argue that if those funds had instead been deployed toward increasing community policing, the payoff in decreased crime would have been far more significant.

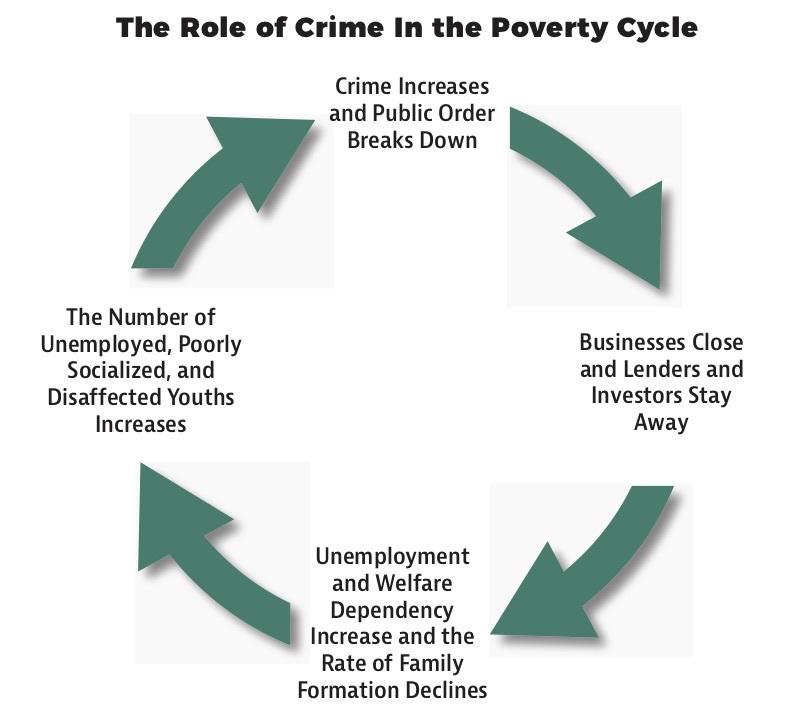

Because most of the communities at the epicenter of the crime explosion were poor and Black, a disproportionate number of the criminals who were arrested and incarcerated were poor and Black as well. Newly enacted sentencing laws ensured that they spent extended periods behind bars, during which time, far from being rehabilitated, they tended to be drawn deeper into the criminal ethos. Regardless of whether prison turned out to be a “school for crime,” all of them were left with criminal records that made them more or less unemployable. As a result, the mass incarceration caused by the punitive approach to crime control tended to raise the level of both crime and unemployment in Black and poor communities, which added momentum to the poverty cycle described in the previous installment in this series.

Note: This brief is an amended excerpt from a longer policy report called “Keeping the Peace: How Intensive Community Policing Can Save Black Lives and Help Break the Cycle of Poverty.” Additional excerpts will be posted in the coming weeks. One will argue that unless we take steps quickly to bring it under control, the new crime wave that began in the spring of 2020 will also be a disaster for Blacks and the poor. A future brief will advocate a specific approach to getting the crime wave under control; namely, “the strategic deployment of large numbers of well-trained and well-managed police officers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods.”

Note: This brief is an amended excerpt from a longer policy report called “Keeping the Peace: How Intensive Community Policing Can Save Black Lives and Help Break the Cycle of Poverty.” Additional excerpts will be posted in the coming weeks. One will argue that unless we take steps quickly to bring it under control, the new crime wave that began in the spring of 2020 will also be a disaster for Blacks and the poor. A future brief will advocate a specific approach to getting the crime wave under control; namely, “the strategic deployment of large numbers of well-trained and well-managed police officers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods.”

For additional information see:

Black Lives Matter – Which Is Why We Need More Police Funding, Not Less

The Late 20th Century Crime Wave Was a Disaster for Blacks and the Poor

Prominent leftist suddenly sees that violence is bad, but for the wrong reason