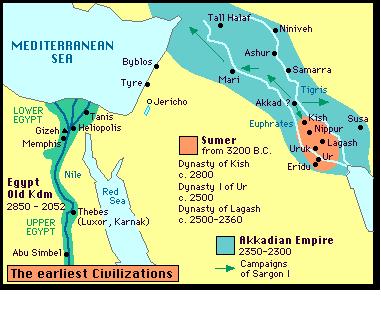

I’ve been reading a new history of Mesopotamia, and something I saw prompted me to look up a story I remember from an old book of mine entitled History Begins at Sumer. It is reported to be the first recorded example of a tax revolt, occurring in the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2300s BCE.

A dynasty of king-priests had ruled over the people for centuries. The Lagash population consisted most of small farmers and herdsmen, fisherman and merchants, and a small urban population of craftsmen and scribes. Most of the land was actually owned by the king-priest, or more properly by the temple, so the people acted as sharecroppers without secure title to their private property. Still, as author Samuel Noah Kramer put it

… in many other respects the economy was relatively free and unhampered. Riches and poverty, success and failure, were at least to some extent the result of private enterprise and individual drive. THe more industrious of the artisans and craftsmen sold their handmade products in the free town market. Traveling merchants carried on a thriving trade with the surrounding states by land and sea, and it is not unlikely that some of these merchants were private individuals rather than temple representatives. The citizens of Lagash were conscious of their civil rights and wary of any government action tending to abridge their economic and personal freedom, which they cherished as a heritage essential to their way of life.

But eventually the dynasty of Ur-Nanshe came to power in about 2500 BCE and proceeded to ruin the finances of the city with building projects and costly wars of conquest. The king-priests raised taxes and seize back property from tenants. Tax collectors aggressively enforced the new duties and imposts by taking cattle, boats, wool, and other goods. Lagash actually imposed a tax on divorce (six shekels) and perfumes (five). The city-state may have invented the death tax, too, as at burials “a number of officials and parasites made it their business to be on hand to relieve the bereaved family of quantities of barley, bread, and beer.”

Finally a new ruler, Urukagina, took power in pitiful and declining Lagash and reversed its fortunes. He fired the tax collectors and lifted most of the hated taxes. According to the ancient scribe relating the story, he “established the freedom” of the people of Lagash. Unfortunately, he died after only a 10-year rule.