- In 2020, citing risks to the state’s coastal economy and ecology, Gov. Cooper got Pres. Trump to add North Carolina to his offshore energy leasing moratorium, finding out later it meant not only no oil and gas exploration, but no wind exploration, either

- Since Trump’s 10-year moratorium would begin July 1, 2022, the Biden administration has been trying to rush “rapid offshore wind development”

- In response, Cooper, some North Carolina congressional representatives, and others have abandoned their concerns for the coastal economy and ecology in favor of a blind pursuit for a political win at all costs

Energy exploration off the shores of North Carolina has long been controversial. For uncertain benefits it threatens disruption of commercial and recreational fishing, economic impacts against coastal communities, depressed tourism from ugly viewsheds, and ecological damages to sensitive underwater environments.

In 2016, Pres. Barack Obama pulled his plans to allow oil and gas exploration in the Atlantic region, originally part of his “all-of-the-above” approach toward domestic energy production. His final five-year plan put 94% of the Outer Continental Shelf off-limits.

On April 28, 2017, Pres. Donald Trump issued an executive order to “encourage energy exploration and production, including on the Outer Continental Shelf.” In 2018, the U.S. Department of the Interior under Trump released a five-year draft proposal for opening up offshore oil and gas exploration that included offshore North Carolina.

In 2019, the U.S. District Court in Alaska ruled against Trump’s attempt to overturn Obama’s memorandum permanently banning offshore oil and gas exploration in the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, a ban issued in the closing days of the Obama administration. This court case set a precedent binding future administrations, too.

In the meantime, political concerns over offshore exploration merged with several other concerns about unknown impacts on fisheries, tourism, coastal and oceanic ecosystems, and the environment, so that by early September 2020 Trump announced a presidential memorandum to remove the waters off the coasts of Florida up through South Carolina from energy exploration for 10 years, beginning July 1, 2022.

On Sept. 16, 2020, Gov. Roy Cooper announced to the press that he had sent Trump a letter urging that the waters off the coast of North Carolina be added to Trump’s 10-year moratorium.

Cooper cited several reasons for his request:

- Threats to “North Carolina’s coastal economy and environment”

- Risks to the state outweighing the benefits

- “North Carolina’s coastal tourism generates $3 billion annually and supports more than 30,000 jobs”

- “Commercial fishing brings in another $95 million to our economy each year”

- The economic importance of “North Carolina’s 300 plus miles of coastline” and estuarine waters and shoreline — “we cannot afford to endanger them”

- “North Carolina’s history of hurricanes” and obvious “risk of storm damage” to offshore equipment

Shortly afterward, Trump added the waters off the coasts of North Carolina and Virginia to his 10-year moratorium. His Sept. 25, 2020, memorandum “prevents consideration of this area for any leasing for purposes of exploration, development, or production during the 10-year period beginning on July 1, 2022, and ending on June 30, 2032.” Trump’s memorandum carries the same legal binding as Obama’s.

A Moratorium on Energy Exploration Includes Wind, Too

While initial reaction hailed the prevention of offshore oil and gas exploration, the full scope of Trump’s protection of the coast of North Carolina from energy exploration became evident later. As explained by the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), it “includes all energy leasing, including conventional and renewable energy.”

Suddenly, the politics of protecting the state’s coastal economy, its marine ecology, its commercial and recreational fishing, its tourism, etc. changed. The people still affected by those concerns now became obstacles, not allies. To Cooper and the new president, Joe Biden, that date of July 1, 2022, became a big problem.

In his first week in office, Biden set a goal of “doubling offshore wind by 2030.” On March 29, 2021, Biden announced “a set of bold actions that will catalyze offshore wind energy” that would include going “up and down the Atlantic Coast.” These actions would result in “rapid offshore wind deployment.”

On April 8, 2021, all five of North Carolina’s Democratic representatives in the U.S. House and two of the state’s eight Republicans — Rep. David Rouzer and Rep. Richard Hudson — urged the Biden BOEM to “take swift action” and “expeditiously begin” finding and leasing wind areas off the coast of North Carolina. Their reason for the panicked rush? The coming moratorium.

Cooper, despite his election-year stand for “North Carolina’s coastal economy and environment,” likewise threw caution to the wind. On June 9, 2021, he announced a political goal for “development of 2.8 gigawatts (‘GW’) of offshore wind energy resources off the North Carolina coast by 2030 and 8.0 GW by 2040.” On cue, the Biden administration used this “goal” as a justification for its push to approve the proposed Kitty Hawk Offshore Wind Project offshore North Carolina (to connect to Virginia’s energy grid).

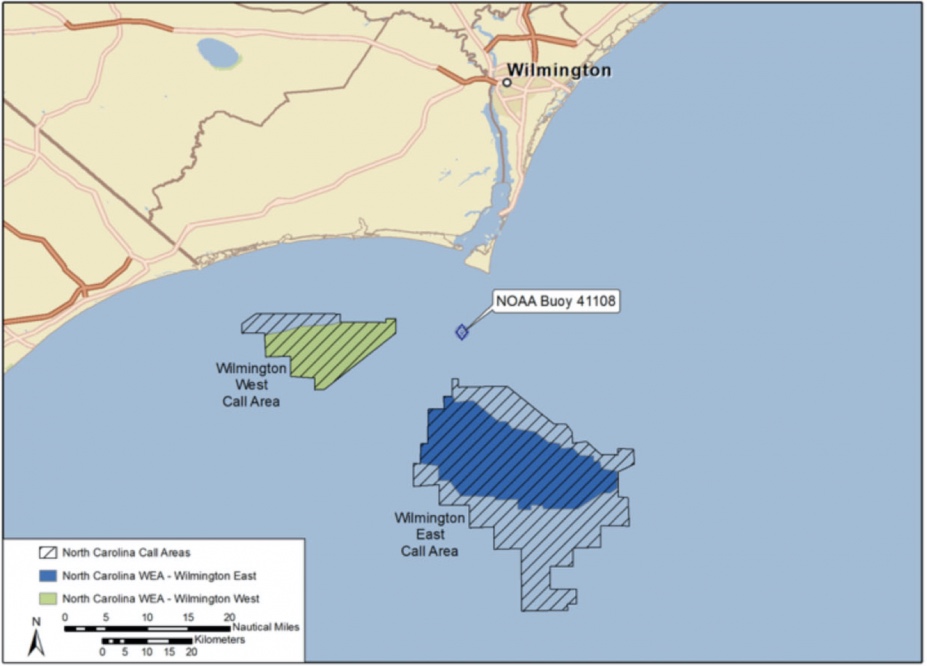

On Oct. 28, 2021, the Biden administration started the process for lease sales “in the Carolina Long Bay area” involving the Wilmington East and Wilmington West projects that would be only a few miles offshore from Brunswick County beaches (see the map).

MAP: Proximity to the southern North Carolina coastline of the proposed Wilmington East and Wilmington West offshore wind projects

Source: U.S. BOEM as published by Port City Daily

Several Brunswick County towns and the county commission have united in opposition to the project, worried about the projects’ negative permanent impacts on their tourism, economy, natural environment, natural resources, and ecology. The projects’ proximity to the shoreline, disrupting the viewshed, is especially a sore spot. While BOEM has approved buffers for other coastal communities potentially affected by offshore wind projects of between 24 to 33.7 nautical miles, BOEM would allow siting of wind turbines for Wilmington East only 15 nautical miles offshore. For Wilmington West, they would be allowed a mere 10 nautical miles offshore.

Even a major political ‘win’ cannot justify not fully considering potential risks

The pursuit of offshore wind development is already enormously expensive, let alone for a variable, unreliable energy resource that is entirely dependent upon when the wind blows. There are much cheaper, much more reliable resources — including zero-emissions nuclear power — that require much, much less disruption of the surrounding environment than does offshore wind.

Nevertheless, offshore wind is a major political goal for the Biden administration as well as the Cooper administration. Standing in the way is a political barrier erected by the Trump administration against offshore leasing for energy exploration, development, or production. This barrier was ironically urged by Cooper for protecting “North Carolina’s coastal economy and environment,” thinking it would affect only oil and gas.

Regardless, the blind pursuit of a political win at all costs is putting the coastal economy and ecology at potentially great risk. How great, we can’t say, because part of this mad rush includes not taking the time to study the manifold risks to North Carolina in order to make a sober assessment of projects’ costs and benefits.