Ever since the end of Prohibition over eight decades ago, North Carolina has been a “control” state for liquor. In North Carolina, government controls the pricing, warehousing, wholesale, and retail sales of liquor.

Not so for beer and wine. Only liquor. North Carolina is a “license” state with respect to beer and wine. Tar Heels interested in beer and wine can find them in many, many places: taverns, bars, restaurants, grocery stores, convenience stores, specialty shops, even pharmacies and other places.

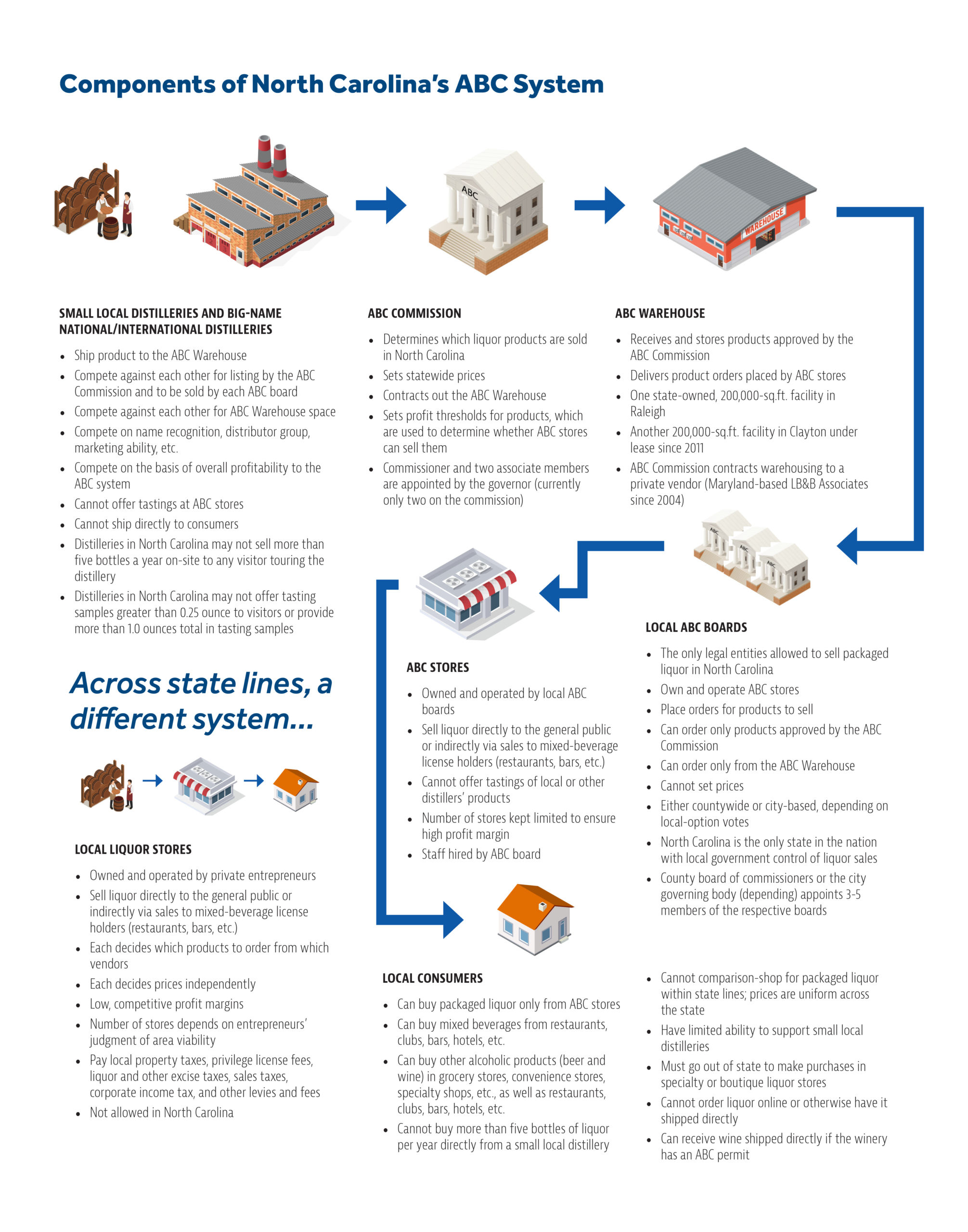

For liquor, however, the instance a bottle leaves a distillery until a consumer purchases it, government controls every step of the way. A bottle’s journey from a distillery to a North Carolina consumer is a needlessly difficult path (click on the picture for a larger image):

This system is not just a maze; it’s a relic. It’s a highly inefficient system that hearkens back to when state leaders of a different era wondered what they could do with Prohibition ending to maintain tight control over people’s access to liquor.

A big reason this system is still around is that undoing it is a huge undertaking, which makes it easier for entrenched special interests to stymie reform.

A bill before General Assembly would cut this Gordian knot. House Bill 971 would make North Carolina a license state for selling liquor. This means it would join North Carolina with the growing majority of license states.

Among other things, HB 971 would:

- Sell off the state liquor warehouse

- Get rid of local ABC boards

- Sell off local ABC stores (proceeds to go to local public schools)

- Stop the practice of the ABC Commission setting liquor prices

- Get rid of bailment charges and surcharges for shipping liquor to the warehouse

- Get rid of the excise tax of 30 percent on the sale of liquor

Those reforms encapsulate the top three recommendations of the John Locke Foundation’s Spotlight paper on liberating North Carolina’s alcoholic beverage control system.

Incidentally, the paper’s fourth recommendation is addressed by HB 363 (now law, it gives craft brewers more freedom to self-distribute) and would also be addressed by HB 378 (the distillery freedom bill).

Here’s what HB 971 would put in place:

- Establish new permits and fees for liquor sales

- Establish new city and county licenses for liquor sales

- Establish a flat excise tax of $28 per gallon on liquor sales

- Set aside a portion (25 percent) of the liquor excise tax for distribution to cities and counties for treatment of alcoholism and substance abuse, for research on alcohol and substance abuse, and for law enforcement

- Set aside $2 million to the Department of Health and Human Services for alcoholism and substance abuse treatment, research, and education

- Set aside $8.5 million for operating and administrative costs of the ABC Commission

- Cap the number of liquor store permits (“off-premises spirituous liquor permits”) beginning at 1,500, with chances to add new ones locally as the population grows

- Set up a three-tiered system as is done in North Carolina for beer and wine (distiller, wholesale, retail) and have detailed protections for liquor wholesalers

The genius of a free state

Treating liquor like beer and wine makes intuitive sense. It’s what two-thirds of states already do. But if anything, it especially makes sense for North Carolina.

After all, this is a state whose own Constitution forbids monopolies as “contrary to the genius of a free state,” a state proud to be “First in Freedom.” Total government control over a legal product is something you’d expect from a socialist dystopia like Venezuela, not here.

With total government control over liquor, North Carolina stands in the way of consumers, local distillers, potential growth in future distillery ventures, potential future growth in retail ventures, greater choice, greater competition, local job creation, and community benefits. But it doesn’t have to.

Modernizing and adopting a license system for liquor in North Carolina would benefit consumers, distillers, and private retailers, as well as future entrepreneurs, local job-seekers, and local communities. It’s a reform that’s long overdue.