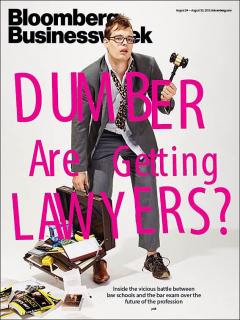

One suspects that law school critic George Leef has read Bloomberg Businessweek‘s latest cover story with interest.

One suspects that law school critic George Leef has read Bloomberg Businessweek‘s latest cover story with interest.

Last August, the tens of thousands of answer sheets from the bar exam started to stream into the National Conference of Bar Examiners. The initial results were so glaringly bad that staffers raced to tell their boss, Erica Moeser. In most states, the exam spans two days: The first is devoted to six hours of writing, and the second day brings six hours of multiple-choice questions. The NCBE, a nonprofit in Madison, Wis., creates and scores the multiple-choice part of the test, administered in every state but Louisiana. Those two days of bubble-filling and essay-scribbling are extremely stressful. For people who just spent three years studying the intricacies of the law, with the expectation that their $120,000 in tuition would translate into a bright white-collar future, failure can wreak emotional carnage. It can cost more than $800 to take the exam, and bombing the first time can mean losing a law firm job.

When he saw the abysmal returns, Mark Albanese, director of testing and research at the NCBE, scrambled to check his staff’s work. Once he and Moeser were confident the test had been fairly scored, they began reporting the numbers to state officials, who released their results to the public over the course of several weeks.

In Idaho, bar pass rates dropped 15 percentage points, from 80 percent to 65 percent. In Delaware, Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon, Tennessee, and Texas, scores dropped 9 percentage points or more. By the time all the states published their numbers, it was clear that the July exam had been a disaster everywhere. Scores on the multiple-choice part of the test registered their largest single-year drop in the four-decade history of the test. …

… Panic swept the bottom half of American law schools, all of which are ranked partly on the basis of their ability to get their graduates into the profession. Moeser sent a letter to law school deans. She outlined future changes to the exam and how to prepare for them. Then she made a hard turn to the July exam. “The group that sat in July 2014 was less able than the group that sat in July 2013,” she wrote. It’s not us, Moeser was essentially saying. It’s you.

“Her response was the height of arrogance,” says Nick Allard, the dean of Brooklyn Law School. “That statement was so demonstrably false, so corrosive.” Allard wrote to Moeser in November, demanding that she apologize to law grads, calling her letter “offensive” and saying that the test and her views on the people who took it were “matters of national concern.” Two weeks later, a group of 79 deans, mostly from bottom-tier schools, sent a letter asking for an investigation to determine “the integrity and fairness of the July 2014 exam.”

Moeser wasn’t swayed. She responded in December, saying she regretted offending people by characterizing the students as “less able”—but maintained that they were relatively bad at taking the exam. In January, Stephen Ferruolo, the dean of the University of San Diego School of Law, asked Moeser to explain how the NCBE scored the test. Moeser rebuffed him, instead inviting Ferruolo to consider the decline in his students’ Law School Admission Test scores in recent years, which, she wrote, “mark the beginning of a slide that has continued.” The implication: Ferruolo and the rest of the people running law schools not named Stanford or Harvard should get used to higher fail rates.