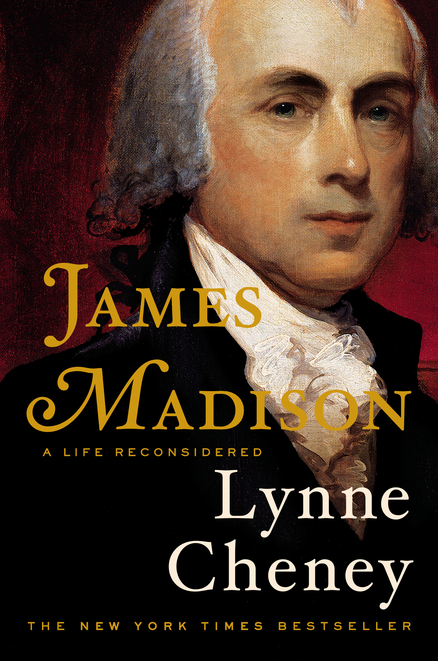

The fourth president has attracted considerable attention in recent years from scholars who write books accessible to general readers. The latest entry in this list of popular biographies, Lynne Cheney’s James Madison: A Life Reconsidered, has attracted particular attention because of Cheney’s theory that Madison suffered from epilepsy.

The fourth president has attracted considerable attention in recent years from scholars who write books accessible to general readers. The latest entry in this list of popular biographies, Lynne Cheney’s James Madison: A Life Reconsidered, has attracted particular attention because of Cheney’s theory that Madison suffered from epilepsy.

Not only a footnote in his life, according to Cheney’s narrative, the epilepsy helped drive Madison’s thinking on issues such as religious freedom. His physical condition also helped guide the course of his political career. (Cheney posits that fear of an epileptic episode likely played a role in Madison’s unwillingness to serve as a European envoy in the opening years of American government under the U.S. Constitution.)

While the documentation of Madison’s health issues has attracted the most attention, this reader found more enjoyment in a review of Madison’s important role in pushing the United States toward a new Constitution and helping the newly formed American government for decades as it charted a course under that Constitution.

People who follow today’s political debates are likely to appreciate this passage from a chapter on Madison’s retirement years.

Madison often responded at length to requests for his commentary on constitutional matters. When Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in McCulloch v. Maryland that the necessary and proper clause of the Constitution allowed Congress to enact legislation merely “appropriate” to carry out its constitutional mandates, Madison offered his critique to Virginia Appeals Court judge Spencer Roane, writing, “What is of most importance is the high sanction given to a latitude in expounding the Constitution which seems to break down the landmarks intended by a specification of the powers of Congress.” He added that “few if any of the friends of the Constitution” who were present at its birth anticipated “that a rule of construction would be introduced as broad and as pliant as what has occurred.” Moreover, he wrote, if such a rule had been set forth in the state conventions, it was hard to believe that the Constitution would have been ratified. When the Speaker of the House, Andrew Stevenson, asked him to expound on “the origin and the innocence of the phrase ‘common defense and general welfare,'” Madison set out a history of the phrase in the Articles of Confederation, the Constitutional Convention, and the ratifying conventions to show that the words were regarded “merely as general terms, explained and limited by the subjoined specifications.”