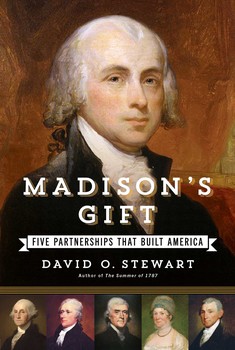

He hasn’t attracted as much attention over the years as George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, but James Madison played a critical role in the American founding. As David Stewart reminds us in the book Madison’s Gift, the fourth president formed one-on-one partnerships with Washington, Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Monroe, and wife Dolley Madison at crucial points in the early history of the American republic.

He hasn’t attracted as much attention over the years as George Washington or Thomas Jefferson, but James Madison played a critical role in the American founding. As David Stewart reminds us in the book Madison’s Gift, the fourth president formed one-on-one partnerships with Washington, Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Monroe, and wife Dolley Madison at crucial points in the early history of the American republic.

With Alexander Hamilton, he did much of the hard intellectual work of creating the constitutional government, leading the fight to ratify the Constitution and writing The Federalist. With George Washington, he undertook the challenges of building the new government and creating the Bill of Rights. He and Thomas Jefferson, though professing to disdain political parties, created a model party that could translate public opinion into a governing mandate while facilitating peaceful changes in government. With James Monroe, he demonstrated that a republican nation could war with a powerful foe, acquit itself decently if not gloriously, and remain true to its ideals. And with Dolley, he created a republican style that matched the open and well-intentioned government over which he presided.

That glittering list of achievements reflects Madison’s extraordinary gifts, and also the gifts of his partners. From Hamilton, Madison gained the vision, fire, and audacity to imagine an entirely new form of government and then with its approval. Madison’s alliance with Washington drew on the incomparable stature and political weight of America’s first citizen. Jefferson shared with Madison his idealism, his sure political instincts, and his intuitive sympathy for individual rights. The partnership with Monroe brought soldierly gravitas and ballast to a presidential administration that was not naturally warlike. And Dolley blessed his days with personal magnetism, warmth, and laughter.

That Madison’s achievements were tied to his remarkable partnerships reflects his focus on making a success of the American experiment in self-government, whether it meant designing a new system of government, solving a specific problem, or respecting the people’s rights. He was eager to make common cause with like-minded souls to reach those overarching goals, without regard for credit or blame. Madison’s great good fortune was to find so many remarkable partners with whom he could join in the important work, and theirs was to be able to call upon Madison’s profound yet affable brilliance.