Governors and state legislators have given away much of their ability to make policy over the last 30 years. Even as state government has grown in size and scope, it has become increasingly dependent on sources of revenue outside of its direct control. It is not coincidental that the first budget action to receive bipartisan legislative support and Gov. Roy Cooper’s signature was a bill to ensure North Carolina could continue drawing down federal funds.

Reihan Salam, president of the Manhattan Institute, wonders in The Atlantic “if the diminishment of state governors reflects the diminishment of state governments“ through reliance on federal funds and other limitations on a state’s ability to set its own course.

Every state, regardless of political coloration, spends far more on Medicaid, public education, and public-employee benefits than it did a generation ago, in no small part because of the availability of federal matching funds, part of a sprawling federal grant-in-aid system, that powerfully influence state spending decisions.

By promising to match state spending, federal grant-in-aid programs lower the effective cost of delivering services that Congress deems desirable, usually with strings attached that limit the autonomy of state officials. The advent of these programs then creates state-level constituencies that are deeply invested in their continuation, which in turn helps ensure that they can never be rolled back or substantially restructured. Even when federal grant-in-aid programs do afford some room for state-level creativity, a certain learned helplessness tends to creep in. State officials are so fearful of losing federal funds that they tend to stay well within the lines.

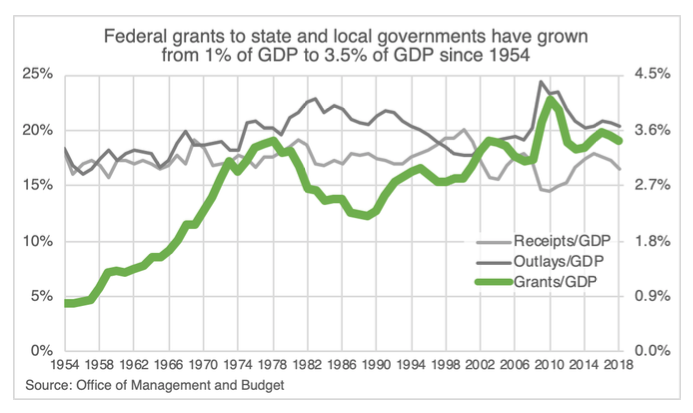

Surprisingly, federal grants do not play a significant role in Daniel J. Hopkins’ analysis of how politics has become increasingly nationalized. Hopkins, a political science professor at the University of Pennsylvania, compares federal receipts as a share of GDP to the correlation between votes for governor and president. This ignores the federal government’s increasing reliance on debt to finance its operations and the increasing role that grants have played. From less than one percent of GDP in 1954, federal grants to local governments now take 3.5 percent of GDP.

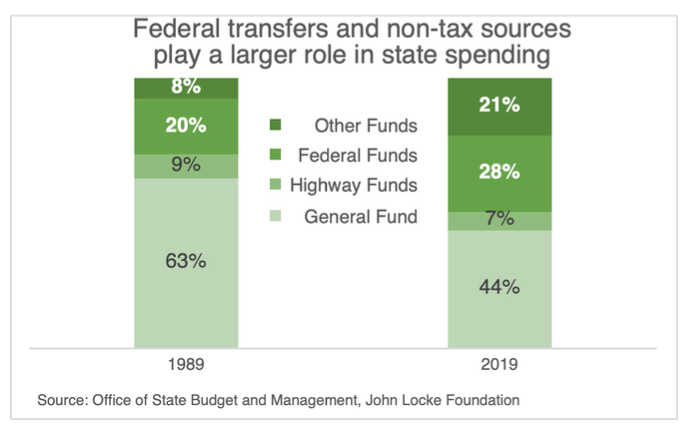

In 1989, federal funds added one dollar for every three in North Carolina General Fund appropriations. By 2019, federal funds added two dollars for every three dollars of appropriations. Other unappropriated funds, from tuition, the lottery, unemployment insurance, and other sources have grown from less than one-tenth of total spending to more than one-fifth.

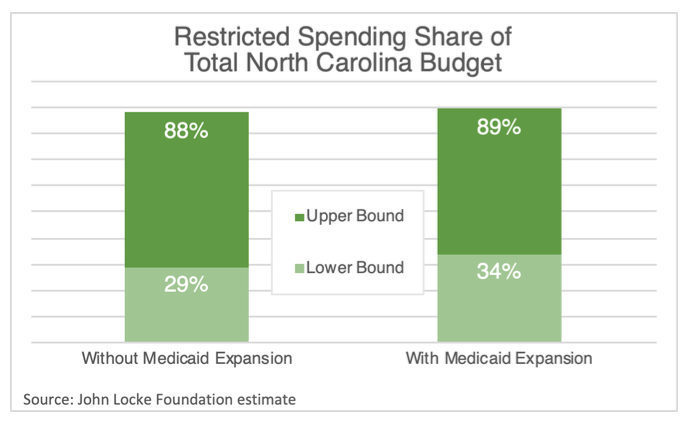

Scholars at the Tax Policy Center examined how much state spending is on autopilot as a result of “constitutional and statutory formulas, federal grant requirements, and court rulings .” They found somewhere between 27 and 80 percent of Virginia’s spending was restricted in 2015. The lower bound included state and federal spending on Medicaid and debt service. The upper bound added in pensions, K-12 education, corrections, TANF, transportation, other federal receipts, and some other state-specific restrictions.

Using the Virginia standard for North Carolina yields a lower bound of 29 percent and an upper bound of 88 percent of total state spending that is restricted. Medicaid expansion would increase the lower bound to 34 percent and the upper bound to 89.5 percent.

The fight over Medicaid expansion is not just about this year’s budget. It is a fight for the ability of future governors and state legislators to set the right course for North Carolina regardless of who is in the White House or Congress. It will take coordinated efforts to rein in debt, ensure teachers and state employees are paid on the job and in retirement, and prepare for the next recession. Coordination at this level demands flexibility that is only available through savings and state tax collections.