Earlier this month the Mercatus Center at George Mason University released a Policy Brief on “The State of Occupational Licensure in North Carolina.” Along with discussing specific North Carolina licenses, the report includes a discussion of the economics and effects of licensing in general and some suggestions for reform for North Carolina.

A snippet:

A SNAPSHOT OF NORTH CAROLINA’S OCCUPATIONAL LICENSURE REGIME

The government of North Carolina has developed extensive licensing requirements, with 22 percent of the workforce licensed and another 8.4 percent certified. North Carolina licenses 188 occupations, including such rarely licensed professions as floor sander, sign language interpreter, and locksmith. …Though for several professions North Carolina boasts less restrictive laws than the national average, in some instances the reverse is true. For instance, North Carolina’s requirements for sign language interpreters—who are only licensed in 22 states—are the fifth highest in the country. North Carolina’s prospective sign language interpreters are required to obtain 1,469 days of education and experience, pay $938 in fees, and pass two exams before they can begin work. Meanwhile, sign language interpreters in neighboring Georgia, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia face no licensing requirements at all.

Similarly, barbers in North Carolina are subject to the fifth most stringent licensing requirements in the United States. A prospective barber in Raleigh may begin work only after accruing 722 days of experience and passing three exams. By contrast, a barber in Atlanta, Nashville, Richmond, or Charleston could begin work more than one year sooner, and take one fewer exam.

Do fire alarm installers need 25 times more training than EMTs?

One aspect of the report I’d like to highlight is its discussion of what report authors term “regulatory mismatches.” As the report explains:

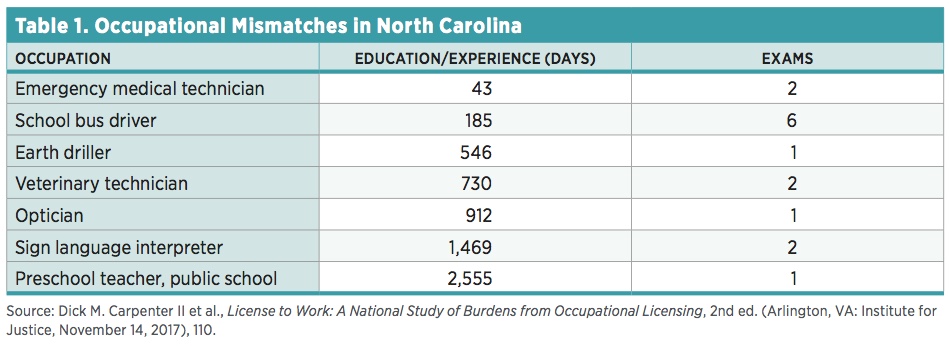

Patterns in occupational licensing requirements contradict the idea that licensure is primarily intended to protect public safety. Occupations that are less likely to involve risk to the public are often more tightly controlled than riskier occupations.

For example, North Carolina’s emergency medical technicians (EMTs) must complete 43 days of training and pass two exams before being licensed to work on an ambulance team. By contrast, North Carolina’s fire alarm installers must complete 1,095 days of education and experience—25 times the amount of training required of EMTs. Pest control applicators, too, are subject to a full 22 months more training than EMTs—731 days in total.

Here is the table from the report illustrating some regulatory mismatches:

Readers interested in ways to reform North Carolina’s outdated occupation licensing system can read my report on the subject, consider the Right to Earn a Living Act (which has passed Arizona and Tennessee), look into other state licensing overhauls (such as in Nebraska and Mississippi), and follow the occupational licensing tag here.