- A large and growing body of academic literature confirms that police presence deters crime and helps maintain public order

- Increased police presence has been shown to be an especially effective way of reducing the homicide rate for Black victims

- The implication is clear: if we want to save Black lives and ensure that the current spike in violent crime does not spiral out of control, we should deploy more police officers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods

On October 7, 1969, the Montreal Police called a wildcat strike. Next morning, the Montreal Gazette described the result:

Hundreds of looters swept through downtown Montreal … as the city suffered one of the worst outbreaks of lawlessness in its history. Hotels, banks, stores and restaurants … had their windows smashed by rock-tossing youths. Thousands of spectators looked on as looters casually picked goods out of store-front windows.

Canadians were horrified by the breakdown in public order that followed the withdrawal of the Montreal police, but they probably weren’t particularly surprised. That police presence helps maintain public order and deters crime, and that an announced withdrawal of police presence might lead to an increase in crime and disorder: these are matters of common sense for most people.

Common sense can be wrong, of course. Psychological and sociological phenomena are complex and poorly understood, and our intuitions can sometimes lead us astray about such things. Not in this case, however. A large and growing body of academic literature corroborates the commonsensical view of the matter: police presence deters crime.

In 2002, economist Steven D. Levitt published a paper in which he summarized four recent studies of the impact of police presence on crime, including two of his own:

Estimating the causal impact of police and crime is a difficult task. As such, no one study to date provides definitive proof of the magnitude of that effect. Nonetheless, it is encouraging that four different approaches … have all obtained point estimates in the range of 0.30–0.70. The similarity in the results of these four studies is even more remarkable given the large previous literature that uniformly failed to find any evidence that police reduce crime — a result at odds with both the beliefs and the behavior of policymakers on the issue.

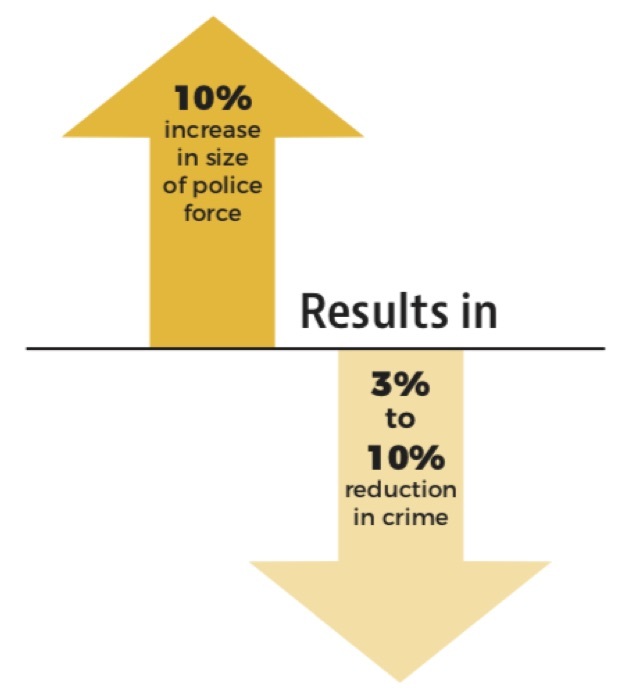

When Levitt says the studies all obtained point estimates in the range of 0.30–0.70, he is talking about what economists call “elasticity”; i.e., the extent to which one economic variable changes in response to a change in another variable. An elasticity in that range means a 10% increase in the size of a police force should result in a 3% to 7% reduction in crime.

That estimate of the extent to which crime declines as police presence increases has held up remarkably well. Using changes in police presence related to terror alert levels in Washington, D.C., in 2006, Jonathan Klick and Alex Tabarrok published new findings about the effect of police presence on crime in the Journal of Law and Economics. They found that “an increase in police presence of about 50 percent leads to a statistically and economically significant decrease in the level of crime on the order of 15 percent, or an elasticity of 0.30.” They also found that, “Most of the decrease in crime comes from decreases in the street crimes of auto theft and theft from automobiles, where we estimate an elasticity of police on crime of 0.86.”

In per capita terms the effects are approximately twice as large for Black victims. In short, larger police forces save lives and the lives saved are disproportionately Black lives.

In 2015 Klick, along with John M. MacDonald and Ben Grunwald, published the results of another study that reached very similar conclusions using a different methodology. They compared neighborhoods that benefitted from regular patrols by the University of Pennsylvania Police Department with similar neighborhoods that did not receive this additional level of police presence and found that “UPPD activity is associated with a 60% … reduction in crime.” According to their calculations, that reduction represented an elasticity of 0.33 for aggregate crime and an elasticity of 0.70 for violent crime.

Summarizing a variety of studies, including the Klick and Tabarrok study described above, a 2016 Obama administration report stated:

Economic research has consistently shown that police reduce crime in communities, and most estimates show that investments in police reduce crime more effectively than either increasing incarceration or sentence severity. … This research shows that police reduce crime on average, and estimates of the impact of a 10 percent increase in police hiring lead to a crime decrease of approximately 3 to 10 percent, depending on the study and type of crime [and] that larger police forces do not reduce crime through simply arresting more people and increasing incapacitation, instead, investments in police are likely to make communities safer through deterring crime.

In 2020, Aaron Chalfin, Benjamin Hansen, Emily K. Weisburst, and Morgan C. Williams, Jr., reported the results of another study of the relationship between police presence and crime. Unlike previous studies, this one disaggregated its results by race:

We find that expanding police personnel leads to reductions in serious crime. With respect to homicide, we find that every 10-17 officers hired abate one new homicide per year. In per capita terms the effects are approximately twice as large for Black victims. In short, larger police forces save lives and the lives saved are disproportionately Black lives.

The implication of all this research is clear. If we want to save Black lives and ensure that the current spike in violent crime does not spiral out of control, we need to deploy more police officers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods. Future installments in this series will discuss how that can be accomplished.

For additional information see:

Black Lives Matter – Which Is Why We Need More Police Funding, Not Less

The Late 20th Century Crime Wave Was a Disaster for Blacks and the Poor

How America Ended Up Underpoliced and Overincarcerated

“Broken Windows Policing”: Good Policy, Bad Name

Prominent leftist suddenly sees that violence is bad, but for the wrong reason