- A new report finds that North Carolina’s forest management plans effectively preserve forests while allowing for recreation and commercial use

- Preserving forests by shutting them away from human interaction has led to overgrowth of vegetation resulting in declining populations of small game and increased risks of forest fires

- Forests are best maintained through private/public partnerships, which allow the land to be used for commercial use to keep overgrowth from happening and to help sustain local economies

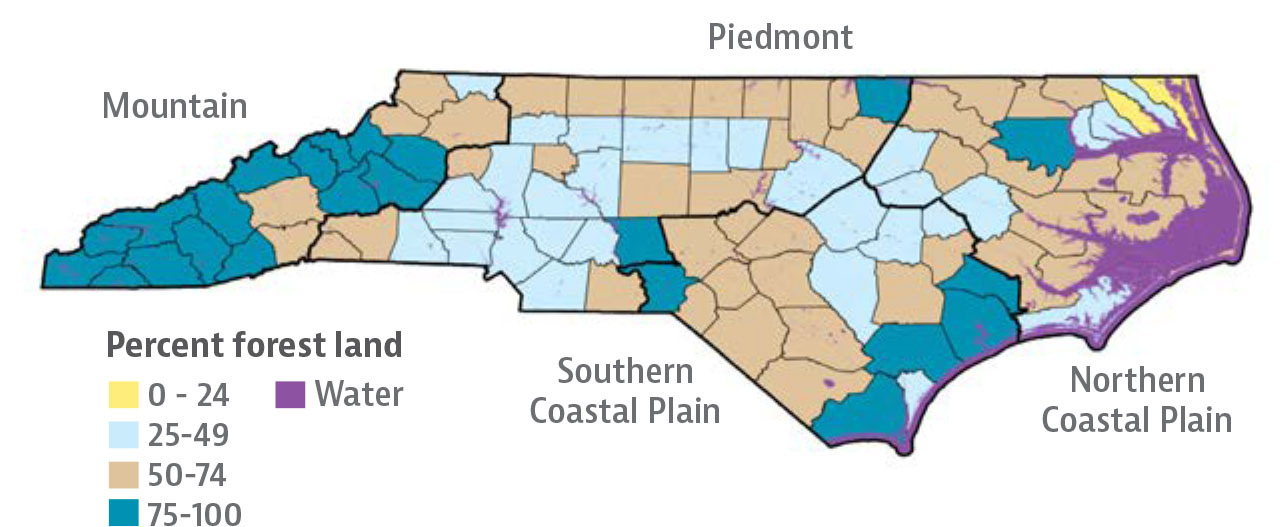

The forest sector plays a large part in the state and local economies in North Carolina. Forestry totaled around $20.6 billion in industrial output and contributed $32.8 billion to the state’s economy in 2020. In a state where over half (54 percent) of the land is forested, the sector sustains over 138,000 full-time and part-time jobs and produces $1.2 billion in international exports.

Because of the importance of forestry to North Carolina, policymakers should not limit the sector. A new report from the John Locke Foundation and the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Michigan finds that North Carolina’s forest management plans effectively preserve forests while allowing for recreation and commercial use. The report, by Jason Hayes, director for environmental policy at Mackinac, recommends North Carolina’s forestry management as a model for other states.

Percentage of forest land in North Carolina, by county

Source: First in Forestry report

Often referred to as “first in forestry,” North Carolina has a long history in forest management. In the late 1800s, George W. Vanderbilt purchased what now is the Pisgah National forest. In 1891, Vanderbilt hired forestry icon Gifford Pinchot to create a plan to sustain the beauty of the forest while generating revenue. Pinchot recommended Vanderbilt also hire German forester Carl Schneck. Vanderbilt wanted Schneck to use an experimental science called “silviculture,” a theory for carefully controlling forest reproduction and growth to meet value and demands. Schneck learned he would need to engage in shared stewardship by collaborating with various stakeholders. Massive harvesting on private land due to the industrial revolution’s demand for resources led many to see Schenck’s idea that forests should be privately owned as controversial. President Theodore Roosevelt sided with Pinchot, who felt forests should be federally managed.

By the 1920s, however, preservationists’ policy prescriptions of federally owned land became the norm. Their ideal was keeping forests “pristine” — in other words, avoiding as much human intervention in forests as possible. It has led to increasing risks of forest fires, however.

Policymakers are now seeking ways to prevent the forest overgrowth that heightens these risks, and they are doing so through negotiations with private companies and through prescribed burns to encourage regrowth. As highlighted by Hayes, North Carolina’s most recent plans are a perfect example of these ideas.

Government policies preventing commercial use of forests harm local economies

The federal government owns 7.8% of the North Carolina’s total acreage, but in some (mostly western) counties, the federal government controls over three-quarters of the total land. These counties face unique challenges in that they rely on profits from harvesting, fishing, and hunting on federally owned land. When activities are limited, the local area is reliant on payments in lieu of taxes (PILT) for basic needs, but PILT money does not always cover the county’s full expenses. In those instances, county taxpayers are expected to fund the remaining balance.

Hayes recounted the 2014 closure of the Stanley Furniture Plant in Robbinsville. The loss of the furniture plant left 400 people out of work — 70% of Robbinsville’s population. State legislators noted that federal policies limited access to forested areas, which raised costs by making it harder to harvest timber near mills.

Limited access to commercial use of forests is likely behind the decline in North Carolina’s sawmills, Hayes found. From 2011 to 2021, the number of sawmills operating in the state fell from 229 to 125. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, sawmill jobs in North Carolina have decreased by about a thousand during that time.

The Nantahala and Pisgah National Forest Land Management Plan gets it right

In January 2022, the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) released its decennial land management plan for the Nantahala and Pisgah national forests, along with an impact statement. Hayes praised the USFS plans for their emphasis on economic and ecological stability.

The plan calls for collaboration between federal, state, and tribal leaders and refines past iterations to include more on “human use, cultural and historical values, recreation, and local communities.” The plan allows for 44% of the forests’ area to be available for lumber harvesting. USFS Planner Michelle Aldridge stressed that not all that area would be cut. The goal is for 0.26% of the approved area to undergo harvesting per year for the next ten years. Aldridge stressed that the harvesting would be part of “carefully designed silviculture prescriptions for restoring healthy forests.”

Hayes commended North Carolina’s forest administrators for relying on input from companies, state and local governments, sportsmen, and the general public. The plan emphasizes the use of Good Neighbor Authority, which allows states, counties, and Indian tribes to conduct activities on federally owned land for management purposes, and Shared Stewardship agreements, which promote collaboration between the federal government, the state, and localities.

Fighting fire with fire: how prescribed fires can ward of the threat of wildfires from overgrown vegetation

Even though wildfires are seen more as a West Coast problem, North Carolina is not immune, and the growing number of people living in or near wooded areas increases the risk. The best way to mitigate wildfire risk is through “spacing and thinning of overgrown trees, removing dead or dying trees, and lessening thick brush and grass,” Hayes wrote. Beyond that, however, an effective way to prevent forest hazards is through prescribed burns, in which overgrown older parts of forests are intentionally burned to encourage new growth.

Overgrown forests are less habitable to classic game such as bobwhite quail and grouse species, so hunting success has decreased over time. The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission states that prescribed burns are “one of the best and most cost-effective methods of managing for wildlife habitats.”

The Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests Land Management Plan emphasizes the importance of fire for developing Western North Carolina’s forests. Prescribed fires can help increase the populations of many influential members of a forest’s ecosystem such as longleaf pines, oak savannas, whitetail deer, and turkeys.

Conclusion

Hayes ended the paper with a set of policy recommendations that could strengthen North Carolina’s plans. They include continued efforts to expand Good Neighbor Authority and Shared Stewardship agreements. Hayes also emphasized that North Carolina should not restrict interstate trade of important revenue sources like biomass pellets. North Carolina’s most recent plans for national forests showcase the importance of collaboration with various stakeholders to carefully implement silviculture ideas. As forest ecosystems around America risk becoming a breeding ground for disasters due to the preservationist mentality that has shaped forest management policy since the early 1900s, states should take a page from North Carolina’s plans for more effective forest management.