- North Carolina cities are experiencing record growth, and new housing is in high demand

- Burdensome zoning regulations and affordable housing policies have driven up housing costs

- Loosening these regulations will expand housing opportunities to middle- and low-income families

People are migrating to North Carolina in droves. The Tar Heel state has seen 10% population growth in just 10 years and is one of only six states gaining a congressional seat based on the latest Census. Most of this growth has been in the urban centers: Wake and Mecklenburg counties. And projections show that two-thirds of future growth by 2035 will be in the Research Triangle or in Charlotte.

North Carolina’s competitive tax climate, temperate weather, and natural attractions like the beaches and the Blue Ridge Mountains continue to draw people to the state. Growth is good news, especially when housing growth keeps up with job growth, as it does in Raleigh and the Durham–Chapel Hill region.

But as we look at other states’ metro areas, namely San Francisco, California, and Austin, Texas, we should carefully examine our policies to avoid their housing mistakes.

Burdensome government red tape on building has disallowed new residential construction in San Francisco. The average home now costs over nine times more than the average income in the city. San Francisco is hemorrhaging the residents that once migrated to the area: now more than 10,000 people a year are leaving for other states.

If North Carolina is able to fend off burdensome regulations that drive up housing costs, our state can keep growing without becoming unaffordable.

In North Carolina, the demand for housing units is up. Yet new home growth is stagnant or below its potential in many areas due to a handful of factors further explained below. As a result, prices are rising.

North Carolina’s average housing costs are below the national average. Yet our housing costs are rising tremendously, often increasing at a rate higher than the national average, especially in the state’s metro areas.

In Raleigh, seasonally adjusted median home values have gone up 31.6% to $423,838 since January 2021 and 109% since January 2013, when the median value was $203,000. Charlotte home values increased by 26.9% over the past year. Nationally, home prices rose 19% from December 2020 to December 2021 (the latest data available). That rise is significantly lower than the rise in prices in North Carolina cities.

Given that housing is keeping pace with job growth in some cities like Raleigh, what is contributing to the unmet demand in the housing market as reflected by the rapidly rising prices? Retirees may be the answer.

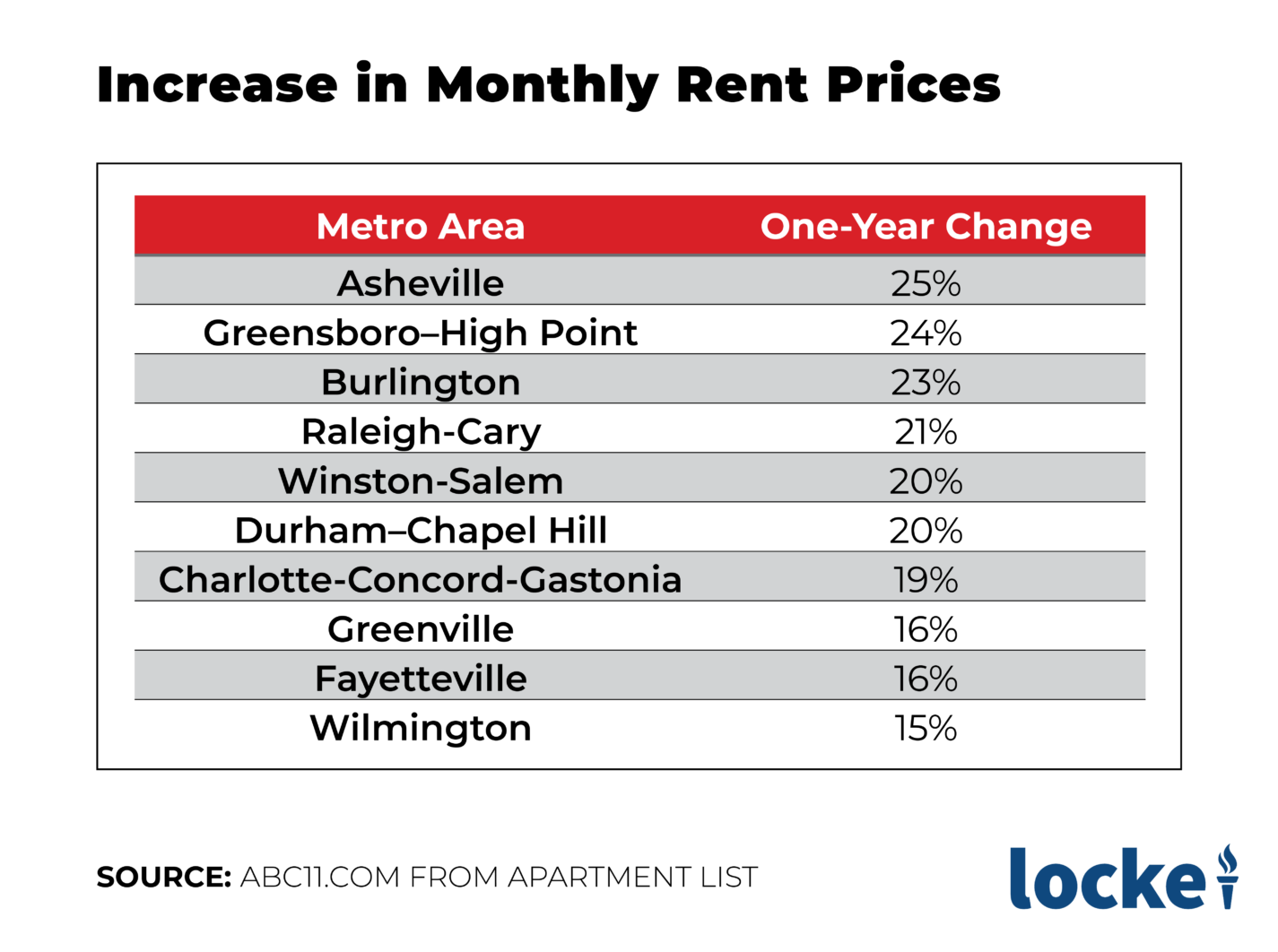

Rent prices are also skyrocketing. Over the last four years, rent prices in Raleigh have risen 20%. North Carolina metro areas are seeing rent increases that surpass the national average increase of 16% as noted in the below table from Apartment List:

Increase in Rental Prices in North Carolina Metro Areas Since Last Year

A 2019 report from the White House Council of Economic Advisers found that a one-percent increase in median rent is associated with a one-percent increase in its rate of homelessness. In the same way, deregulation of the housing market would reduce homelessness.

Some claim, however, that we need more government-directed affordable housing solutions.

Mandatory affordable housing policies, issued at the state and local levels and at the national level by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, are well-intended. But they force homebuilders to designate a portion of their new homes at below-market prices. This has two impacts. First, it discourages new home construction, which restricts available supply and helps drive up prices. Secondly, because the homebuilders take a loss on these units, they raise prices on their other units, passing along the financial hit to new homebuyers and renters.

Middle-class families, who do not qualify for affordable housing but cannot afford the increased prices of the other new homes, are squeezed out the most. Eventually what remains is a stratified city composed of the wealthy who can afford the high-priced houses combined with low-income residents in the subsidized housing, with a growing homeless problem. The middle class vanishes further to the suburbs.

New housing units are in high demand, yet restrictive zoning regulations worsen housing affordability by artificially limiting the housing supply. Consumer demand and preferences should be directing housing markets, not local governments.

Housing codes currently give more weight to the preferences of an area’s existing residents. People are shut out of desirable regions, often close to job centers, due to zoning measures that prevent the addition of more affordable housing options.

A piece referenced by Carolina Journal columnist and former Locke president John Hood states that new housing is oftentimes effectively illegal due to onerous zoning, regulatory, and licensing restrictions that block new, highly demanded dwellings.

Restrictive requirements on accessory dwelling units (ADUs), like in-law suites or basement apartments, are imposed in some cities. Other cities do not permit ADUs at all. This ban disallows a homeowner and potential new resident from a positive mutual exchange in the market. ADUs should be an obvious way to help alleviate cities’ housing supply problem.

Tree protection ordinances control tree cutting on private property. Individuals are better able to make aesthetic and environmental decisions about their own lawns. These ordinances could be costly and time-intensive for residents to navigate. They discourage residential growth and give unnecessary powers to local politicians.

Open space requirements and rural buffers around cities and towns are arbitrary policies guaranteed to drive up prices in the area. These policies are a nod to current residents and a deterrent to newcomers.

Some school districts have argued for government-provided affordable housing for teachers. This detrimental policy would make the government a landlord, a business no government should be engaged in. Policies of this kind are another weak attempt to address the symptom of rising housing costs and not the true cause. Government-provided housing to teachers would further distort the housing market.

Such restrictions are political tools. They reveal local officials’ priorities and demonstrate that lower-cost housing options are not really a priority. Loosening these zoning regulations will help provide housing to middle and low-income families.

Yes, more duplexes and triplexes raise concerns about threatening the character of a community. But government restrictions and political central planning are not the answer. Individuals and property owners must be free to make their own choices. Property owners are almost always better stewards of the environment and their communities. The “common good” is necessarily built on the freedom of the individual.

Part 2 of this series will discuss the opportunity North Carolina leaders have to address skyrocketing housing prices.