Count Gene Epstein among those unconvinced that the American economy might benefit from a dose of inflation. He explains why in his latest “Economic Beat” column for Barron’s.

“Rising prices help companies increase profits; rising wages help borrowers repay debts,” opined the New York Times last week (“In Fed and Out, Many Now Think Inflation Helps,” Oct. 26). “Inflation also encourages people and business to borrow money and spend it more quickly.”

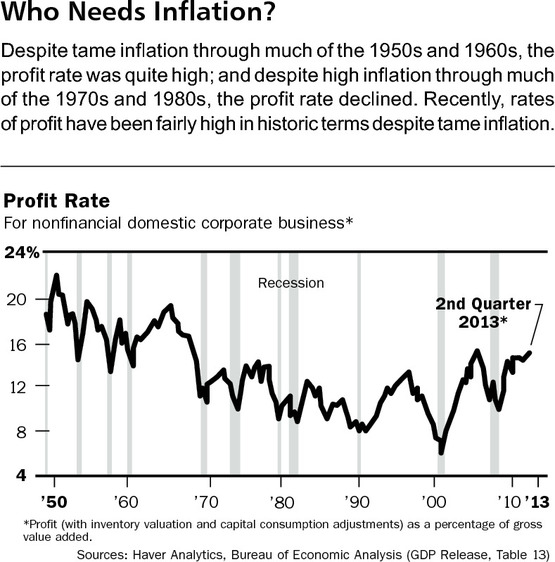

Somehow that prescription didn’t work out so well in recession year 1974, when the CPI jumped 12.3%, while the economy shrank. And as the chart on this page shows, despite the claim that profits benefit from rising prices, actual profit rates were much lower in 1974 than they have been over the recent expansion.

To focus on prices as the driver of profits is reminiscent of the old joke about selling at a loss and making it up on volume. Business activity is motivated by profit, not prices. The price of the output matters for profits, but the cost of the inputs — principally, labor — matters just as much. What really matters for profits, then, is the spread between the cost of the inputs and the prices of the outputs. Before we decide that the slow rise in prices is significantly impairing business activity, we should find out if profitability is suffering. …

… The chart does show that even for domestic nonfinancial corporations, the rate of profit has been higher than usual, even higher than during the late-1990s, when GDP growth ran an enviable 4% per year. The chart also indicates that profit rates over the decades have been unrelated to rates of inflation: highest in the relatively low-inflation decades of the 1950s and 1960s, and then moving lower in the high-inflation 1970s and 1980s; moderate in the low-inflation period of the 1990s, and then moving higher after 2000. …

… THE SIMPLE INSIGHT that business focuses on the spread between the cost of the inputs and the price of the outputs helps explain how business activity can flourish even when prices are falling — normally called “deflation,” which happened in the U.S. in the late 19th century. A study published by the mainstream American Economic Review called “Deflation and Depression: Is There an Empirical Link?” concludes, “A broad historical look finds many more periods of deflation with reasonable growth than with depression, and many more periods of depression with inflation than with deflation.”

So even the idea that deflation is to be feared is at least open to question. It’s a lot more interesting than the hoary notion that inflation is somehow our newfound friend.