Some things last, and some things don’t. Beyonce’s 2008 single “Single Ladies” is an enduring song. “Shut Up and Let Me Go” by The Ting Tings is not. Raleigh continues to hope its free downtown bus, the R-Line Circulator, has more lasting significance than The Ting Tings. Still, recent decisions to end the free circulator bus service in Nashville and Washington, D.C., suggest it may be time to end the experiment here as well.

Launched in 2008, R-Line ridership climbed to nearly 300,000 people in 2012 but was below 150,000 in 2017 after GoRaleigh decided not to add a third bus and expand service to Cameron Village. The following year, Raleigh and the Raleigh Transit Authority began to reconsider the R-Line. Ridership has climbed since then, in part due to City Council’s opposition to electric scooters.

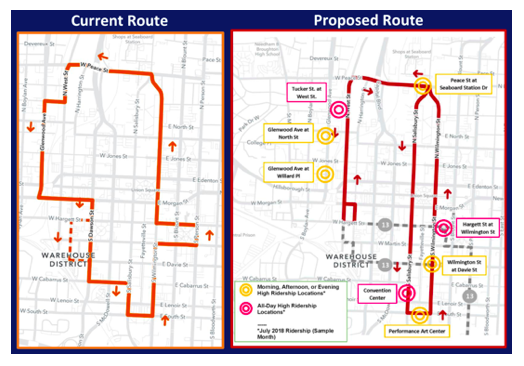

Price is clearly not a factor in what a public meeting flyer describes as the “declining performance of the R-Line Route” despite a “growing downtown population” and “more downtown destinations to serve.” Spokesman Nathan Spencer told the Raleigh News and Observer that wait times between buses were as long as 30 minutes, twice as long as targeted. An unscientific online survey suggests it could take longer to ride the R-Line than to walk between stops.

Different cities, similar stories

Raleigh is not the only city struggling to attract people to free bus service. The DC Circulator in Washington began in 2005 with a $1 fee and added routes over time. In February 2019, Mayor Muriel Bowser set aside $3.1 million to make the Circulator free. City Council reinstated fares as of October 1 in part because the subsidies do not help low-income riders. Ridership there has also declined.

Nashville launched its free Music City Circuit in 2010. Voters in 2018 rejected a $9 billion transit initiative that “would have increased the city’s sales tax, hotel-motel tax, business and excise tax, and car rental tax” to pay for “26 miles of light rail, four new rapid bus lines, four crosstown bus lines, improved service on existing buses, 19 transit centers, and a suite of improvements to signals, sidewalks, and bike infrastructure.” After its referendum defeat, the transit authority changed its name and found itself with “budget woes” that led to charging higher fares or eliminating service. It halted the free bus service on September 29th.

Other services that remain free differ greatly in their operations and finances. The Downtown Connection in New York City has been funded by local businesses since its launch in 2003. The service uses seven shuttle buses equipped with WiFi that run every 10-15 minutes. Circulators in Houston, Columbus, and Baltimore launched free services like Raleigh’s between 2010 and 2014. Houston Downtown Management District, Houston First Corporation, Harris County, and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) provide funds for the Houston service. Columbus’ is financed, like Raleigh’s, from the existing transit budget.

Baltimore uses parking taxes, grant money, advertising and money from nonprofit organizations to contract with a private provider in competition with buses operated by the Maryland Transit Authority. A 2017 report found the system was “fiscally unsustainable” after it lost $11.6 million between its launch in 2010 and 2014, but the city entered a new three-year $26 million contract in June 2019.

The future of the R-Line

Compared to Baltimore’s service, the R-Line’s $900,000 cost to operate two buses on the 3.6-mile loop seven days a week seems like a bargain. Although GoRaleigh tracks how many people embark and disembark at each stop, they generate no revenue for the free service. In addition, there is no dedicated funding source for the R-Line and not even a specific appropriation in the city budget. It simply comes out of GoRaleigh’s total budget, and the number is GoRaleigh’s estimate of cost based on hours of operation and number of buses and drivers.

At 150,000 riders, that $900,000 estimate means a cost of $6 per rider, about the cost of an UberX from the Convention Center to Sullivan’s Steakhouse. Uber vouchers, however, would end up being much more expensive or temporary because they would be more popular. Because all the costs exist regardless of how many people hop on the R-Line, the subsidy would fall to $3 per rider at 300,000 people per year.

City officials explain that falling ridership is not the only reason for route changes. Other factors include more downtown residents, shopping, and dining. The current loop route can also create a long wait for the next bus, which the new out-and-back route can hasten, though it would not necessarily cut total commute time.

Raleigh City Council should take a more comprehensive look at the R-Line beyond questions of the route, and ask why the service exists. To date, it has been aimed at tourists and people attending events at the convention center, but with more housing downtown, GoRaleigh seems to think residents will use it more.

When I rode it in December, there were, on average, seven other people with me. They ranged from a couple of people who looked homeless, some high-income millennials, government workers, and even middle school students fresh from an after-school stop at the Morgan Street Food Hall.

Surely some of the residential riders would be willing and able to pay as circulator riders in Philadelphia and Washington do. If it helps downtown businesses, should the Downtown Raleigh Alliance and the Raleigh Chamber provide funds instead of taking nearly $1 million from other transit priorities? The business groups and some of their members already support the Regional Transportation Alliance, which advocates for transportation around the Triangle.

It is time for the business community to put a ring on the R-Line. If downtown businesses do not see the value, perhaps it would be better for GoRaleigh to stop talking and let the R-Line go.