In his 1985 address to the North Carolina Foundation for Research and Economic Education (NC FREE), Gov. James Martin laid out three keys to a more conservative view of government. The first was to elect more conservative, business-oriented political leaders. The second was to reduce taxes at all levels. The third was to keep government spending in check and improve government productivity and efficiency.1 These core principles reflected a broad agenda for sustained conservative reforms Martin and his political and policy advisers had developed months prior.2

Just over 25 years after Martin’s address, North Carolina voters elected a Republican legislative majority that elevated conservative, business-oriented political leaders to leadership positions in the General Assembly. Under their leadership and the leadership of their successors, they have passed budgets and advanced policies that reflect the conservative view of government Gov. Martin articulated decades earlier—the elimination and reduction of taxes on all North Carolinians, prudent spending and savings, and a renewed focus on improving government productivity and efficiency. The 2017-19 biennial budget continues that tradition.

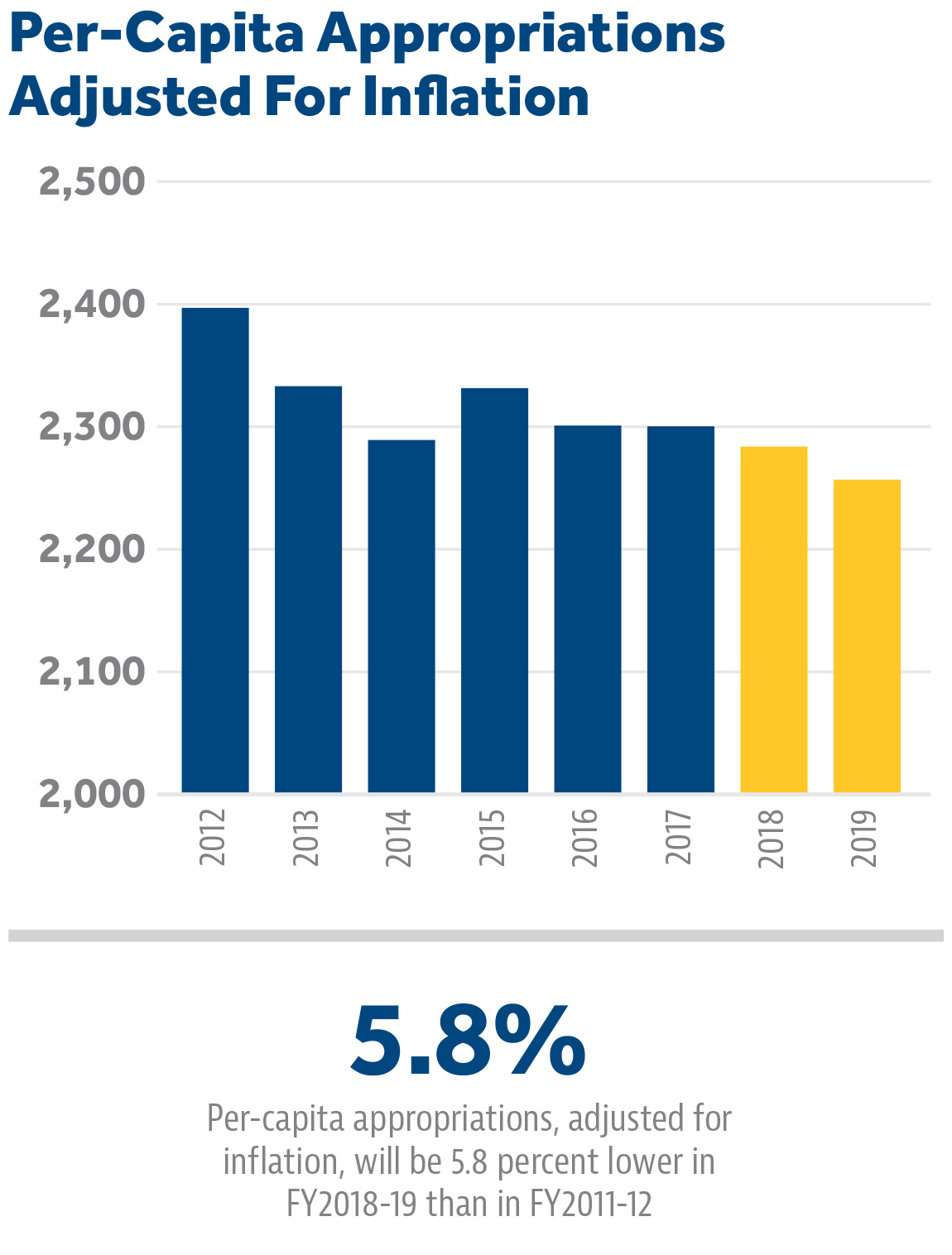

With the support of two Democrats and the abstention of a third in the House, the General Assembly overrode Gov. Roy Cooper’s veto of a budget that largely continues the restraint needed for long-term fiscal sustainability. The spending increase is larger than the average over the past five years, but it spends less per person when adjusted for inflation.

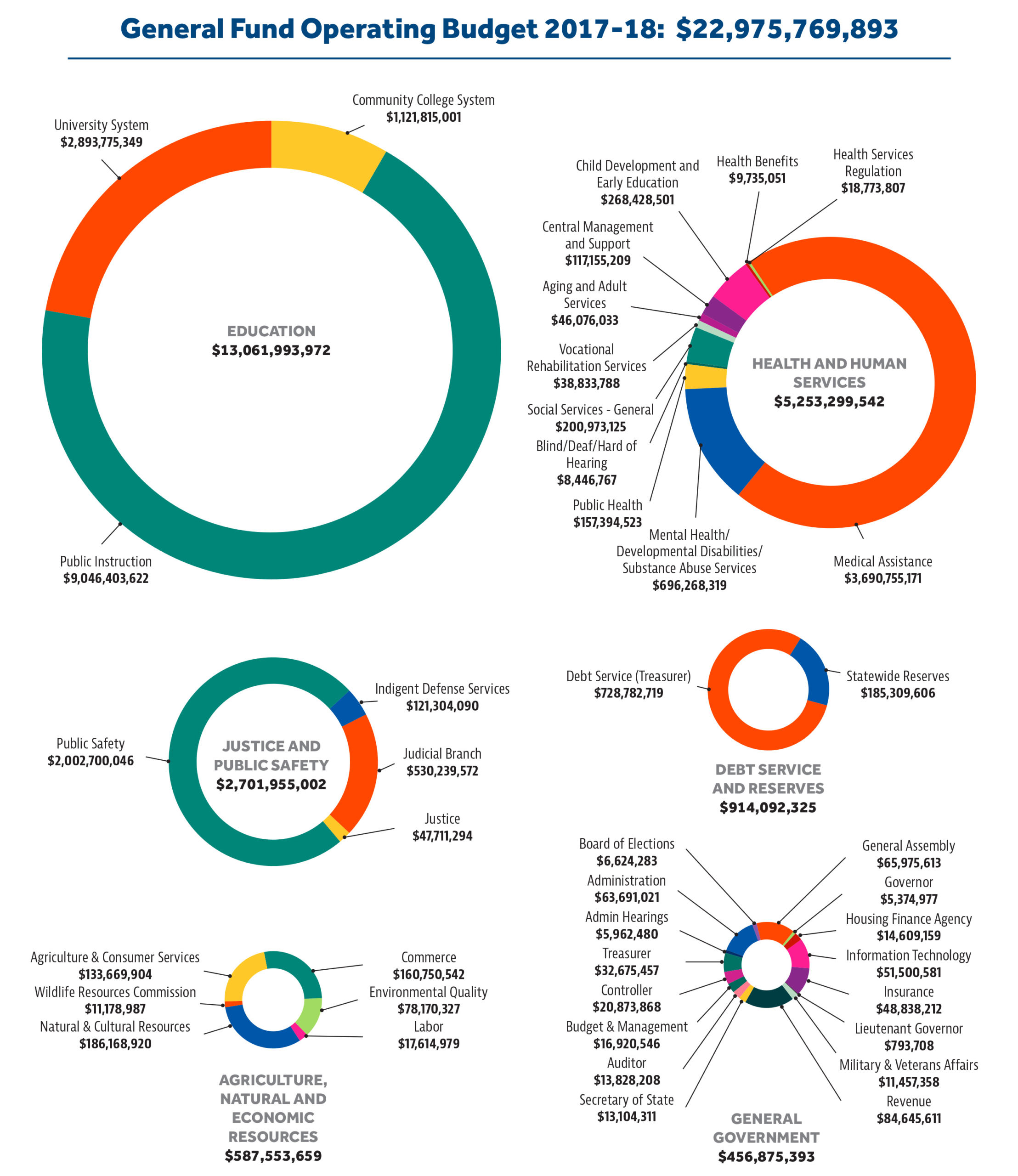

The budget will spend $23 billion in state tax dollars in the fiscal year that ends June 30, 2018, and $23.6 billion the following fiscal year. It includes another $3.7 billion each year for transportation projects and sets the stage for another round of broad income tax reductions in January 2019. Overall General Fund appropriations will grow by $1.3 billion, or 5.9 percent, over two years. Such budgetary restraint means state government will take less, adjusted for inflation, from every North Carolinian.

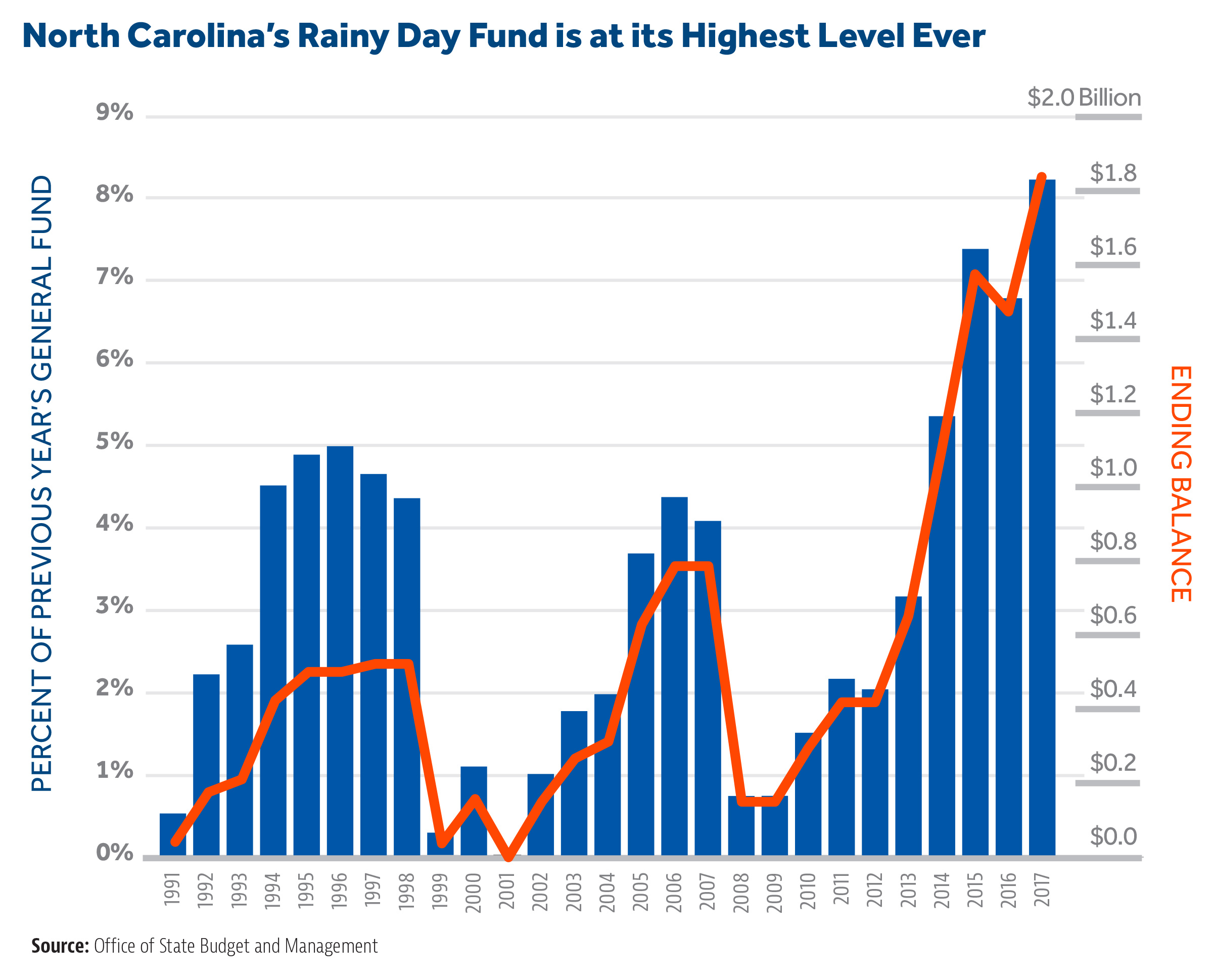

Legislators also set aside $263 million for the Savings Reserve, state government’s “rainy-day fund,” in addition to restoring $100 million that had gone to relief for residents affected by Hurricane Matthew. They devoted $125 million to repairs and renovations of government-owned facilities. Provisions in the budget, and in a bill passed earlier this year, should make future funding of the rainy-day fund and state capital needs more secure.

On the personnel side, teachers will receive, on average, a 9.6 percent pay raise over two years, state employees will receive a $1,000 raise, and other state-funded salaries will also rise. Across all agencies, the state will pay $642 million, or 5.6 percent, more in salaries from the General Fund in Fiscal Year (FY) 2018-19 than in FY2016-17. Adding health insurance and retirement benefits to salary, total compensation climbs $967 million, or 6.5 percent. The budget also includes a provision (Section 35.21) to study whether the state is allocating compensation resources in the most productive way and addressing the unfunded liability for future health care costs.

Savings

When a government spends less than it collects in taxes, there is more opportunity to address unfunded liabilities or respond to natural disasters or economic downturns. Currently, the Savings Reserve Account contains the equivalent of about one month of state spending at current levels. That amount is still nowhere near the share of annual state spending necessary to weather a recession, but it is more as a share of spending than at any time in its history.

The General Assembly has created a mechanism to ensure the adequacy of the Savings Reserve Account, instituting mandatory transfers beginning in FY2018-19 and placing restrictions on how its funds can be used. The new law sets a lower bar of 15 percent of new tax revenue after tax law changes for the year if the Savings Reserve is below the threshold agreed upon by the Office of State Budget and Management and the Fiscal Research Division of the General Assembly.

The budget bill itself includes a provision, taking effect in 2019, to set aside 4 percent of total General Fund tax revenue in a single pool to cover capital investments, repairs, renovations, and debt service. This Capital and Infrastructure Reserve replaces the Repairs and Renovations Reserve, which previous law mandated to receive 25 percent of unreserved fund balances but which rarely did in past budgets. Paying for capital from existing funds without adding new debt, and making debt service the first priority for funds in this new reserve, should help North Carolina keep its AAA bond rating.

Low spending and an adequate rainy-day fund should mean less temptation to hike taxes when the next recession comes. The budget is not set to spend every dollar, and savings can offset some of any future unplanned reductions in revenues. If spending and taxes are predictable, people can make long-term plans. The reader may recall that sales tax hikes in the 2000s began as temporary. The first became permanent after repeated extensions; the second was kept temporary when the new Republican majority, overriding Gov. Beverly Perdue’s veto, let the tax expire in 2011. Regularly renewed temporary taxes were no way to run a state, and they seem unlikely to return in the next downturn if the General Assembly stays on its current path. A commitment to lower spending and to set aside savings provides needed fiscal predictability, consistency, and responsibility.

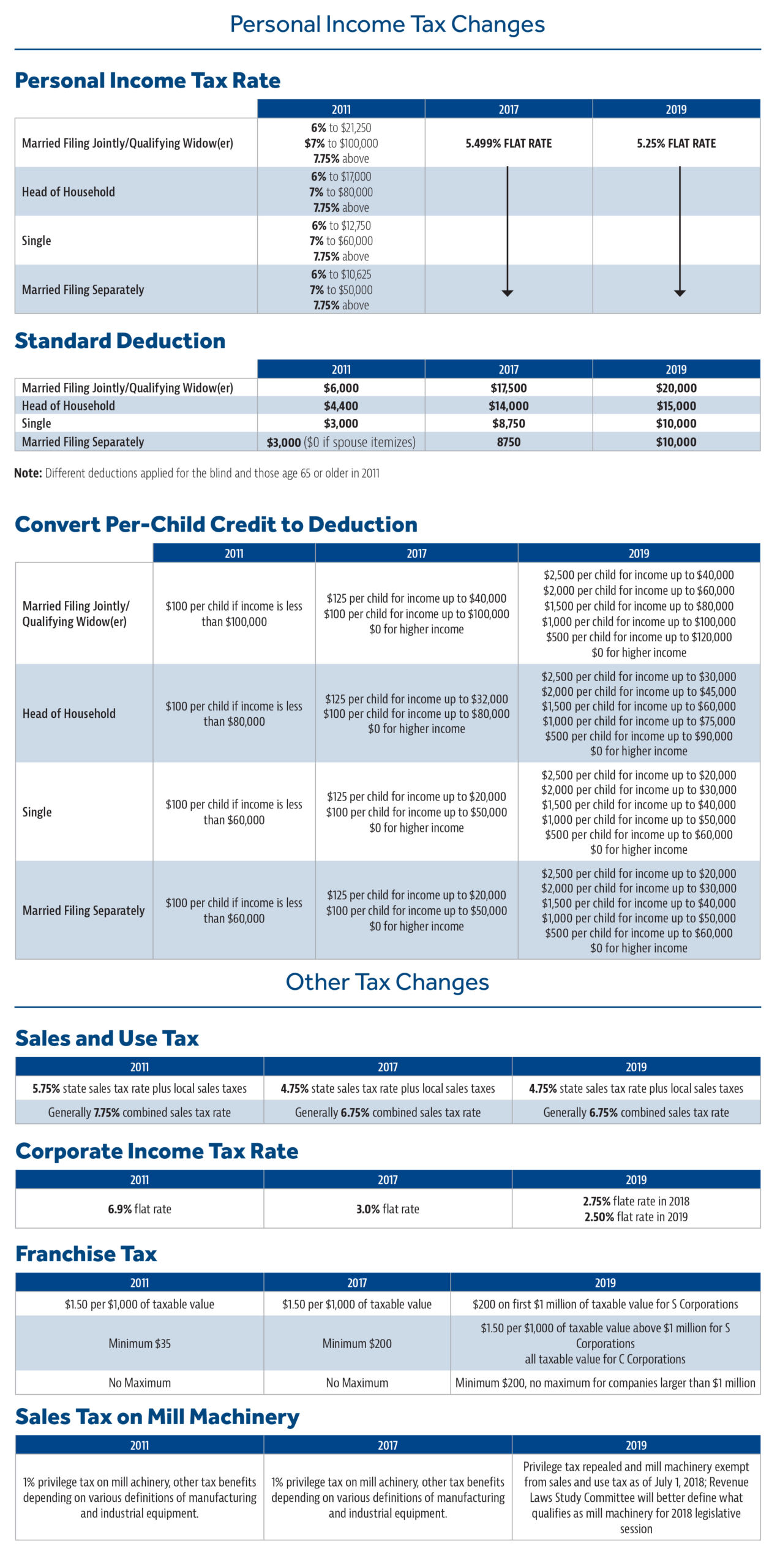

Taxes

Tax changes in the biennial budget are generally broad-based, with lower corporate and personal income tax rates, a higher standard deduction, repeal of the sales tax on mill machinery, and a reduction in the franchise tax for small companies. The budget also changes how taxes are reduced for families with children. Beginning in January 2019, income tax rates will drop for corporations and individuals, and the standard deduction will increase. Broad reductions in tax rates or increases in the standard deduction do not “give away” the state’s money, as some have claimed.3 Instead, lower taxes limit the ability of legislators to give money collected from some citizens to favored organizations or people. A larger standard deduction has a greater impact for those with less income and makes it less likely for wealthier taxpayers to try gaming the system with itemized tax deductions.

Unlike lower tax rates and a larger standard deduction, which reduce taxes for anybody paying the personal income tax, converting the per-child tax credit to a tiered tax deduction will mean slightly higher taxes (from $21.25 to $49.50 per child) for married couples filing jointly who have taxable income of $60,000 to $100,000 after all changes take effect. It seems likely that legislators will address this problem with larger deductions for that income range when they return in 2018, if not sooner.

A lower franchise tax reduces the cost of starting or growing a business in the state. More importantly, it does so without picking winners and losers. Reducing a tax for a wide range businesses, as opposed to granting special carve-outs or incentives, means energy suppliers, Hollywood studios, multinational companies, and recipients of taxpayer-funded grants in recent years are placed on equal footing with small-business owners.

Legislators could have reduced tax burdens in ways that provided more marginal economic gains, such as repeal or reform of the capital gains tax, but the changes they enacted are largely positive. Fortunately, the budget does not include a proposed increase in the mortgage interest and property tax deduction that would have had little benefit for most people or the economy.

The $529 million tax cut legislative leaders advertised mostly takes effect in January 2019, which means just six months of the lower revenue show up in the budget. Its full-year impact will be closer to $1 billion beginning in FY2019-20.

Transparency

Several provisions improve the ability of management, legislators, and the public to understand state government finances and operations, and to hold government accountable for performance.

While the budget provides no new funds for the Office of State Budget and Management (OSBM) to create a website that makes state budgets easier to understand and analyze, lawmakers reiterated their expectation to have a website by January 2018 and provided funds so the Department of Health and Human Services could remove Social Security numbers from its databases. The inclusion of personally identifiable information in financial databases was one of the factors that has kept more information on these programs unavailable online.

The N.C. Community College System keeps its money to plan an enterprise resource planning system that helps its institutions manage their finances and other business processes. The University of North Carolina System and the Department of Public Instruction each receive appropriations to begin planning similar systems to improve their respective fiscal operations. The statewide accounting system in the State Controller’s Office is also slated for an update with appropriations to begin planning and design.

Finally, some nonstate entities that receive government funding must now report to OSBM their planned activities and outcomes, though there is no follow-up check to see how they perform.

Education

The education budget fully funds enrollment growth and increases salaries for all school personnel. Teachers receive, on average, a 3.3 percent raise in the first year and a 9.6 percent raise over the biennium. Principals receive higher pay and have their salaries based on school size and performance. Assistant principals move to a new salary schedule that pays them 1.7 percent more than teachers with comparable credentials and experience.

A Joint Legislative Task Force on Education Finance Reform will evaluate paying for schools based on the needs of each student, rather than on multiple enrollment- and personnel-based formulas, which can simplify school funding while making it more responsive. The Opportunity Scholarship Program will receive its scheduled $10 million increase and has future increases over the next 10 years included in the base budget, so a new class of students each year can find private alternatives. The budget provides initial funding for education savings accounts (ESAs) that can be used to pay for multiple qualifying educational expenses, rather than just tuition at a private school.

The Superintendent of Public Instruction gains $700,000 to hire as many as 10 additional employees, while the State Board of Education loses both vacant and filled positions. The Board, which has filed suit to stop a state law granting more authority to the State Superintendent, will lose its ability to hire private counsel. The Department of Public Instruction will be audited and will have to cut $7.3 million by the end of FY2018-19 at the discretion of management.

The budget places renewed emphasis on early childhood education and career and technical education. It creates a new Associate Superintendent of Early Education and a B-3 Interagency Council to integrate early childhood programs and elementary schools. Additionally, the N.C. Community College System will assume control of the state’s apprenticeship program, which had been housed at the Department of Commerce.

Elizabeth City State University receives $4.8 million over two years to stabilize its operations. The Brody School of Medicine at East Carolina University will receive $4 million each year in recurring funds for the same purpose. Although they are categorized similarly, the differences in funding indicate differences in the needs of the programs.

Two appropriations will make higher education more accessible. First, in-state students at Elizabeth City State University, Western Carolina, and UNC-Pembroke will pay $500 per semester for tuition, and out-of-state students will pay $2,500 through a new NC Promise program that will add $11 million in annual funds beginning in FY2018-19, bringing the total appropriation for the program to $51 million. Second, senior citizens will receive the opportunity to audit classes for free at any UNC campus. To help with accountability across the UNC system, the Board of Governors will receive an appropriation for staffing of its own, thus no longer needing to rely on the UNC General Administration staff to provide information and support.

Two appropriations will make higher education more accessible. First, in-state students at Elizabeth City State University, Western Carolina, and UNC-Pembroke will pay $500 per semester for tuition, and out-of-state students will pay $2,500 through a new NC Promise program that will add $11 million in annual funds beginning in FY2018-19, bringing the total appropriation for the program to $51 million. Second, senior citizens will receive the opportunity to audit classes for free at any UNC campus. To help with accountability across the UNC system, the Board of Governors will receive an appropriation for staffing of its own, thus no longer needing to rely on the UNC General Administration staff to provide information and support.

Community colleges received $1 million in 2016 to develop an enterprise resource planning system (ERP) to manage operations and finance. The Department of Public Instruction received $29 million for business systems, including an ERP, and the UNC system received $10 million for data management and a new ERP. These systems are intended to share information with one another and with a statewide ERP at the Office of the State Controller that received $13 million in nonrecurring funds for the biennium. A 2015 presentation estimated the total cost of a comprehensive ERP system at $301 million with the promise that managers, legislators, and the public will be able to understand the cost of running the government and use it to gauge the return on their investment.

General Government

Legislators took $1 million in funding from the Governor’s office and $10 million from the Justice Department, made the Speaker of the House and President Pro Tem of the Senate primarily responsible for defending the constitutionality of state laws, and limited the ability of the Governor and Attorney General to hire private counsel for lawsuits.

Reorganizations include a transfer of the Human Relations Commission, which deals with housing discrimination, from the Department of Administration, where it was one of a hodgepodge of offices, to the Office of Administrative Hearings, the state’s regulatory court system. The Industrial Commission, which deals with workers’ compensation and other injury claims, moves from the Commerce Department to the Department of Insurance. And the Employment and Workforce Development Commission moves from the governor’s office to the Department of Public Instruction.

Health and Human Services

In the Department of Health and Human Services budget, the biggest news is what did not make the budget—a proposed expansion of Medicaid, the state portion of which would have been funded by a tax on hospitals and the federal portion of which would have grown the total federal contribution nearly 25 percent, to $13 billion a year. This unrealistic and unworkable idea was dead on arrival.

As mentioned in the education section, a new formal structure will connect early childhood education efforts in the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Public Instruction. Another 3,525 children will have slots available for them in the NC Pre-K program, thanks to a $27 million funding increase.

For children in troubled families, the budget includes provisions and new funding to further reform the child welfare system, with an emphasis on foster homes for children from state-recognized tribes. And there is also new funding to tackle the opioid addiction problem.

Justice and Public Safety

Although the Senate included language that would create a separate department for adult and juvenile corrections, the final budget keeps the structure of the Department of Public Safety intact. The North Carolina Commission on the Administration of Law and Justice report earlier this year recommended the state “raise the age” at which a person could be tried as an adult, to 18 for all misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. This brings North Carolina in line with every other state. The budget appropriated $997,600 over two years to plan for these changes to take effect. It also recommended improvements in local courts. The budget provides funding for 96 new deputy clerks by July 2019 and 31 new assistant district attorneys to help improve access to the courts. Overall funding for Justice Public Safety increased $100.2 million.

Natural and Economic Resources

The Division of Environmental Assistance and Customer Service would have been eliminated in the Senate budget. It survives, but with fewer staff in its regional offices and without the Utility Savings Initiative, which is transferred to the State Energy Office. Shellfish and water infrastructure receive special attention and additional funding.

Despite years of research concluding that targeted incentives do not work, funding for Job Development Investment Grants (JDIG) and the One North Carolina Fund receive only temporary reductions totaling $13 million. A provision opens a new category for large facilities ($500 million and 1,750 employees) that can be financed through JDIG. Incentives for film productions remain grants, despite Gov. Cooper’s attempt to make them tax credits again, but funding each year will be more than $30 million, an increase from $15 million. The Commerce and Agriculture departments received more than $5 million to market North Carolina and food products to the rest of the world.

Transportation

Airports across the state will receive $132 million of the $7.2 billion for transportation funding over the next two years for capital improvements and repairs. The Ports Authority will receive a $10 million increase in funding and will be given more independence with its own fund under the Highway Trust Fund. Lawmakers continue to prop up the Global Transpark with $800,000 in appropriations over two years. Also in transportation, bridge preservation and maintenance of roadside environments receive dedicated funding, rather than being lumped together with other projects in the General Maintenance Reserve. The bridge preservation program reaches $85 million in recurring funding in the second year. Roadside environments, such as wildflowers and rest areas, receive $105 million each year.

Employee Compensation and Retirement Benefits

State employees besides teachers and principals will receive raises of $1,000 per year and three extra days off they can use at any time. Retired state employees will receive a permanent 1 percent cost-of-living increase in pension payments. No other changes were made to the pension system, as State Treasurer Dale Folwell initiates measures to change the internal operations of state investments on behalf of employees and retirees.

Health benefits for employees and retirees were complicated by a court ruling that higher premiums for retirees violated their contracts, even if those premiums were in line with changes for active employees. The State Health Plan’s governing board approved changes for 2018 that would charge $25 monthly premiums for employees who currently pay nothing, and increase premiums from $15 to $50 a month for employees with more comprehensive insurance. A budget provision makes new state employees hired in 2021 or later ineligible for state health benefits in retirement.

Conclusion: Good Times But Caution Ahead

The Republican-led General Assembly has had a good track record of assembling sound, fiscally responsible budgets. Its latest General Fund budget, while spending less per person adjusted for inflation than authorized for the current year, sets a long-term path for appropriations and taxes that may require a future course correction.

In April, we wrote that the Senate’s tax cut did not portend a looming crisis, but our analysis was based on General Fund growth of roughly 2.5 percent per year. Instead, the final budget grows 3.1 percent in the first year and 2.7 percent in the second year, and could go higher when the General Assembly makes budget adjustments in 2018.

The final budget also opens a hole in what had been a firm baseline for spending. Before 2013, the budget would automatically increase to cover the same services, just for more people at higher prices. The General Assembly fixed the baseline to maintain spending from year to year. A provision to include “adjustments for statutory appropriations and other adjustments as directed by the General Assembly” in the base budget opens the possibility of making future baselines more like the old system. The provision’s main purpose is to incorporate annual $10 million increases in funding for Opportunity Scholarships for the next 10 years, as mentioned earlier. It sets a troubling precedent, even though the funds support worthwhile programs, and the legislature should debate spending changes each year.

Taxes, meanwhile, may be $1 billion lower each fiscal year once fully implemented, but the cuts will not be immediate. The $529 million tax cut legislative leaders advertised mostly takes effect in January 2019, which means just six months of the lower revenue show up in the budget.

Despite our concerns, the potential challenges this budget could leave in the longer term are significantly different from the budgets passed between 2001 and 2010, when nonrecurring revenues were repeatedly tapped to cover recurring costs. Perhaps legislators will refrain from adding new appropriations when they return next year, keep the budget on track, and continue the conservative legacy of Gov. Martin. Today’s legislative leaders should continue the commitment to lower taxes, keep government spending in check, and improve government productivity and efficiencies.

Endnotes

- “North Carolina Foundation for Research and Economic Education: Raleigh, December 3, 1985,” in Poff, Jan-Michael, Ed., Addresses and Public Papers of James Grubbs Martin: Governor of North Carolina, Volume 1: 1985-1989, Raleigh, N.C.: Division of Archives and History, Department of Cultural Resources, 1992, p. 219.

- Hood, John, Catalyst: Jim Martin and the Rise of North Carolina Republicans, Winston-Salem, N.C.: John F. Blair Publisher, 2015, p. 181.

- “Editorial: Still time to fix state budget into one that helps all North Carolinians,” Capitol Broadcasting Company. June 16, 2017.

Appendix: Budget History

Use the scroll bar beneath each chart to see the historical budget numbers from 2012-13 to 2018-19 (enacted).

| Budget Item | 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community College System | 1,036,253,406 | 1,015,960,648 | 1,042,254,665 | 1,064,979,479 | 1,101,549,741 | 1,121,815,001 | 1,141,757,845 |

| Public Instruction | 7,740,033,655 | 7,767,677,973 | 8,047,204,764 | 8,343,570,526 | 8,775,522,781 | 9,046,403,622 | 9,425,109,426 |

| University System | 2,654,293,281 | 2,574,834,589 | 2,619,320,008 | 2,733,406,480 | 2,862,337,955 | 2,893,775,349 | 2,967,775,032 |

| TOTAL EDUCATION | 11,430,580,342 | 11,358,473,211 | 11,708,779,436 | 12,141,956,485 | 12,739,410,477 | 13,061,993,972 | 13,534,642,303 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aging and Adult Services | 43,775,629 | 41,058,227 | 42,325,463 | 43,107,883 | 44,960,137 | 46,076,033 | 45,149,105 |

| Central Management and Support | 59,934,322 | 87,884,150 | 91,859,176 | 93,707,618 | 114,977,769 | 117,155,209 | 122,769,405 |

| Child Development and Early Education | 257,992,791 | 244,119,926 | 217,264,044 | 226,298,909 | 236,311,387 | 268,428,501 | 278,332,315 |

| Health Benefits | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2,904,652 | 9,656,055 | 9,735,051 | 9,779,090 |

| Health Services Regulation | 13,868,713 | 15,088,538 | 14,648,581 | 15,367,241 | 16,956,467 | 18,773,807 | 19,396,718 |

| Medical Assistance - General Fund | 3,517,694,237 | 3,403,784,495 | 3,557,689,464 | 3,492,782,816 | 3,601,178,797 | 3,690,755,171 | 3,801,681,212 |

| Medical Assistance - NC Health Choice | 79,333,533 | 58,657,858 | 41,664,162 | 11,142,398 | 1,096,448 | 459,248 | 396,409 |

| Mental Health/Developmental Disabilities/Substance Abuse Services | 684,396,459 | 694,877,629 | 685,735,274 | 594,775,049 | 586,025,861 | 696,268,319 | 705,030,589 |

| Public Health | 141,273,403 | 137,196,721 | 134,350,082 | 135,808,756 | 168,603,041 | 157,394,523 | 154,985,218 |

| Services for the Blind/Deaf/Hard of Hearing | 8,178,832 | 6,259,562 | 7,862,366 | 7,134,764 | 8,351,352 | 8,446,767 | 8,507,081 |

| Social Services - General | 165,890,670 | 166,931,985 | 181,693,767 | 178,733,754 | 200,052,088 | 200,973,125 | 205,204,844 |

| Vocational Rehabilitation Services | 32,646,949 | 37,789,780 | 35,674,091 | 35,394,738 | 38,429,222 | 38,833,788 | 39,055,491 |

| TOTAL HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES | 5,004,985,538 | 4,893,648,871 | 5,010,766,471 | 4,837,158,578 | 5,026,598,624 | 5,253,299,542 | 5,390,287,477 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigent Defense Services | 114,392,085 | 115,353,915 | 112,097,792 | 115,996,406 | 123,335,549 | 121,304,090 | 122,280,359 |

| Judicial Branch | 459,324,171 | 460,433,998 | 467,489,915 | 484,738,414 | 516,499,973 | 530,239,572 | 539,023,422 |

| Justice | 75,881,016 | 77,916,197 | 49,865,692 | 53,813,594 | 58,697,198 | 47,711,294 | 46,511,531 |

| Public Safety | 1,655,121,297 | 1,694,053,490 | 1,726,665,179 | 1,849,918,998 | 1,957,530,666 | 2,002,700,046 | 2,020,592,037 |

| TOTAL JUSTICE AND PUBLIC SAFETY | 2,304,718,568 | 2,347,757,599 | 2,356,118,577 | 2,504,467,412 | 2,656,063,386 | 2,701,955,002 | 2,728,407,349 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admin Hearings | 4,034,413 | 4,161,843 | 4,362,362 | 4,760,004 | 5,328,568 | 5,962,480 | 6,010,687 |

| Administration | 61,168,961 | 65,691,829 | 63,142,066 | 59,197,708 | 64,231,863 | 63,691,021 | 63,396,752 |

| Board of Elections | 4,657,890 | 5,321,362 | 5,746,256 | 5,830,808 | 6,643,797 | 6,624,283 | 6,686,614 |

| Cultural Resources | 64,656,884 | 63,735,195 | 63,699,683 | Natural and Cultural Resources | |||

| General Assembly | 53,526,151 | 52,177,008 | 52,492,588 | 57,564,053 | 65,191,661 | 65,975,613 | 65,973,007 |

| Governor | 5,075,289 | 7,392,557 | 7,514,880 | 7,800,031 | 7,702,618 | 5,374,977 | 4,976,409 |

| Housing Finance Agency | 1,206,312 | 8,308,412 | 18,241,954 | 21,618,739 | 50,660,000 | 14,609,159 | 30,660,000 |

| Information Technology | N/A | 12,000,000 | 51,334,084 | 51,500,581 | 51,646,845 | ||

| Insurance | 38,101,418 | 35,680,961 | 35,750,972 | 36,646,772 | 42,337,439 | 48,838,212 | 48,314,700 |

| Lieutenant Governor | 577,865 | 623,842 | 673,312 | 678,271 | 706,252 | 793,708 | 771,497 |

| Military & Veterans Affairs | N/A | 9,180,907 | 8,177,436 | 11,457,358 | 8,960,743 | ||

| Revenue | 76,447,305 | 76,257,110 | 80,074,647 | 79,762,784 | 83,204,372 | 84,645,611 | 85,483,970 |

| Secretary of State | 11,528,018 | 11,372,903 | 11,487,924 | 11,707,673 | 12,797,190 | 13,104,311 | 13,314,943 |

| State Auditor | 10,001,822 | 9,603,808 | 10,079,189 | 12,797,190 | 13,591,502 | 13,828,208 | 13,780,531 |

| State Budget & Management | 7,037,296 | 9,798,642 | 9,035,797 | 22,170,703 | 30,690,112 | 16,920,546 | 10,255,244 |

| State Controller | 29,709,456 | 27,072,137 | 21,515,786 | 22,826,554 | 23,265,407 | 20,873,868 | 23,243,476 |

| State Treasurer | 680,172,834 | 731,448,810 | 725,310,771 | 26,193,235 | 37,671,766 | 32,675,457 | 33,043,914 |

| TOTAL GENERAL GOVERNMENT | 1,047,901,914 | 1,108,646,419 | 1,109,128,187 | 390,735,432 | 503,534,067 | 456,875,393 | 466,519,332 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture & Consumer Services | 101,995,409 | 109,225,597 | 109,593,702 | 111,911,173 | 165,330,427 | 133,669,904 | 122,853,685 |

| Commerce | 111,355,718 | 70,933,128 | 84,985,680 | 78,433,237 | 177,366,251 | 160,750,542 | 146,314,688 |

| Environment and Natural Resources | 119,159,663 | 148,356,237 | 154,855,321 | Environmental Quality, Natural and Cultural Resources | |||

| Environmental Quality (DENR FY2012-13 through FY 2014-15) | Environment and Natural Resources | 78,053,692 | 112,648,970 | 78,170,327 | 77,012,714 | ||

| Labor | 15,174,110 | 14,939,968 | 14,143,243 | 14,559,038 | 16,581,057 | 17,614,979 | 17,819,951 |

| Natural & Cultural Resources | Cultural Resources, Environment and Natural Resources | 160,933,673 | 185,609,116 | 186,168,920 | 175,032,995 | ||

| Wildlife Resources Commission | 18,476,588 | 12,449,258 | 11,160,578 | 10,162,776 | 10,467,033 | 11,178,987 | 10,843,541 |

| TOTAL AGRICULTURE, NATURAL AND ECONOMIC RESOURCES | 366,161,488 | 355,904,188 | 374,738,524 | 454,053,589 | 668,002,854 | 587,553,659 | 549,877,574 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debt Service (Treasurer) | 646,602,823 | 701,744,120 | 695,310,771 | 707,081,977 | 703,102,238 | 728,782,719 | 772,075,116 |

| Statewide Reserves | 48,960,102 | 171,787,127 | 108,566,945 | 171,713,580 | 128,535,236 | 185,309,606 | 208,444,807 |

| TOTAL DEBT SERVICE AND STATEWIDE RESERVES | 695,562,925 | 873,531,247 | 803,877,716 | 878,795,557 | 831,637,474 | 914,092,325 | 980,519,923 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENERAL FUND OPERATING BUDGET | 20,203,307,952 | 20,236,217,414 | 20,668,098,140 | 21,207,167,053 | 22,425,246,882 | 22,975,769,893 | 23,650,253,958 |

| 2012-13 | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highway Fund | 1,951,500,000 | 2,025,600,000 | 2,017,200,000 | 2,051,200,000 | 2,048,690,000 | 2,190,963,770 | 2,251,497,688 |

| Highway Trust Fund | 1,119,250,000 | 1,171,460,000 | 1,234,600,000 | 1,091,818,853 | 1,371,280,000 | 1,547,128,291 | 1,585,824,162 |

| TOTAL TRANSPORTATION | 3,070,750,000 | 3,197,060,000 | 3,251,800,000 | 3,143,018,853 | 3,419,970,000 | 3,738,092,061 | 3,837,321,850 |

Sources

- General Fund FY2012-13 through FY2014-15, OSBM OpenBudget; FY2015-16 through FY2016-17, OSBM Recommended Base Budget for 2017-19; FY2017-18 through FY2018-19, Joint Conference Committee Report on the Operating, Capital, and Expansion Budget (Senate Bill 257) June 19, 2017

- Transportation FY2012-13 through FY2014-15, Governor’s Recommended Budget 2017-19, Appendix Tables 3B and 3C; FY2015-16 through FY2016-17, OSBM Recommended Base Budget for 2017-19; FY2017-18 through FY2018-19, Joint Conference Committee Report on the Operating, Capital, and Expansion Budget (Senate Bill 257) June 19, 2017