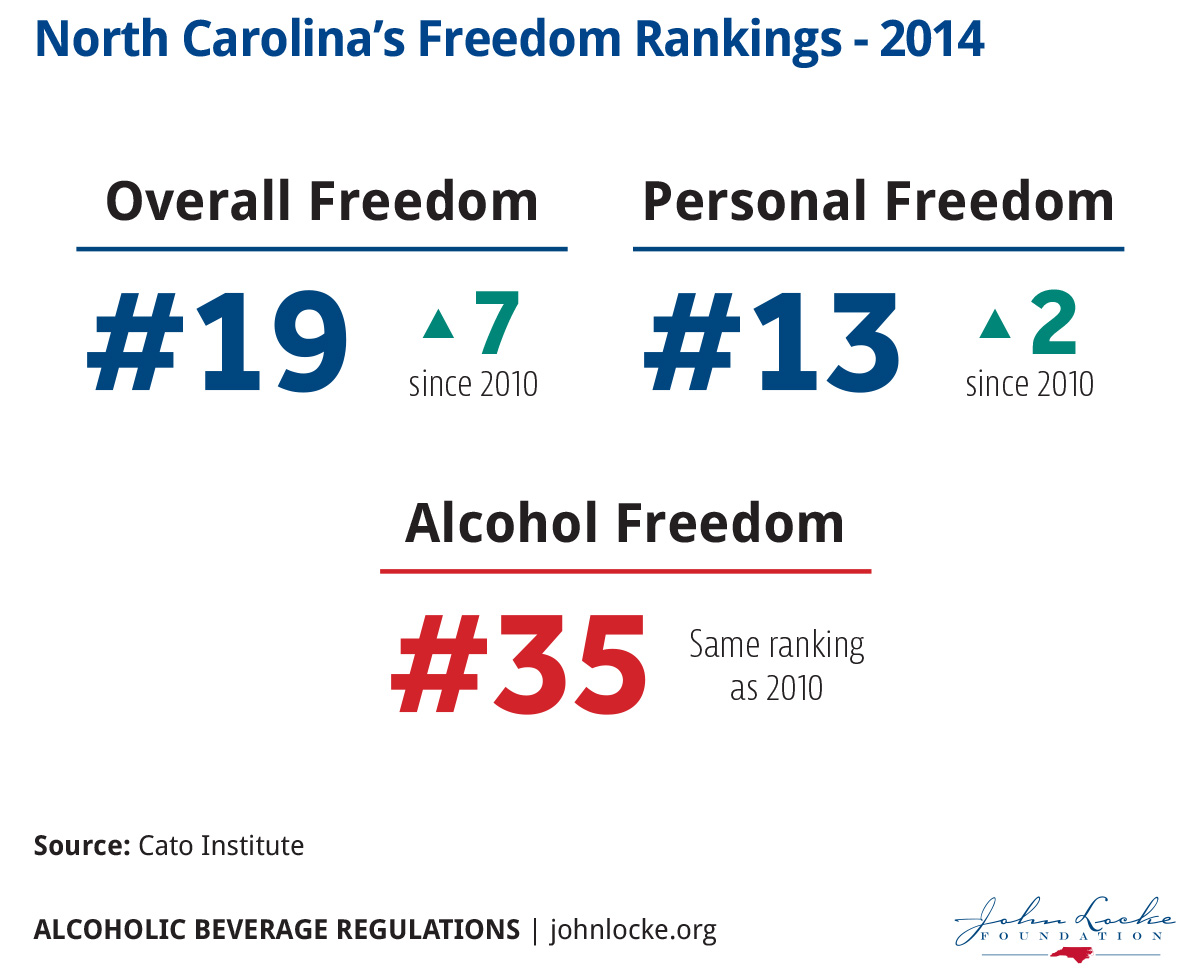

The Cato Institute regularly publishes a report titled Freedom in the 50 States.1 According to the most recent edition, since 2010, North Carolina has improved substantially, advancing from 26th to 19th place in the overall rankings. Unfortunately, in the “alcohol freedom” category, we continue to languish in 35th place.2 This overregulation of alcoholic beverages harms the North Carolina entrepreneurs who would otherwise enter the market as producers and sellers; it harms the North Carolina consumers who would otherwise

enjoy a wider range of alcoholic beverages at lower prices; and it harms the North Carolina economy as a whole that would otherwise be growing at a faster rate. If we truly want North Carolina to be “first in freedom,” we need to reduce the burden that excessive regulation places on the production, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages.

Bootleggers and Baptists

In 2014, the economists Adam Smith and Bruce

Yandle published a book with the provocative title, Bootleggers and Baptists: How Economic Forces and Moral Persuasion Interact to Shape Regulatory Politics.3 As they explain in the preface:

Durable social regulation evolves when it is demanded by both of two distinctly different groups. “Baptists” point to the moral high ground and give vital and vocal endorsement of laudable public benefits promised by a desired regulation. … “Bootleggers” are much less visible but no less vital. Bootleggers, who expect to profit from the very regulatory restrictions desired by Baptists, grease the political machinery with some of their expected proceeds. They are simply in it for the money. …

The theory takes its name from the classic example of laws requiring liquor stores to close on Sundays, which were supported by both local alcohol bootleggers and anti-alcohol Baptists. … Both members of the politicking coalition are necessary to win. The Baptists enable accommodating politicians to say the action is the “right” thing to do and have folks believe them. The bootleggers laugh all the way to the bank — and may occasionally share their gains with helpful politicians.4

When it was originally put in place, the regulatory regime that governs the production, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages in North Carolina was presumably supported by an alliance that included — not just metaphorically but literally — bootleggers and Baptists. Nowadays, while some Baptists no doubt still take an interest in alcoholic beverage regulation, they are joined by a broad spectrum of concerned citizens who, regardless of their religious affiliation, worry about the harm that alcohol abuse inflicts, not just on the abusers themselves, but also on their families and on society as a whole. As for the bootleggers, their role is now filled by government bureaucrats, wholesale distributors, large brewers and distillers, and other interest groups who benefit from the regulation of alcoholic beverages.

The Liquor Sale Monopoly

The most extreme alcoholic beverage regulations pertain to “spirituous liquor,” defined in the North Carolina General Statutes as:

Distilled spirits or ethyl alcohol, including spirits of wine, whiskey, brandy, gin and all other distilled spirits and mixtures of cordials, liqueur, and premixed cocktails, in closed containers for beverage use regardless of their dilution.5

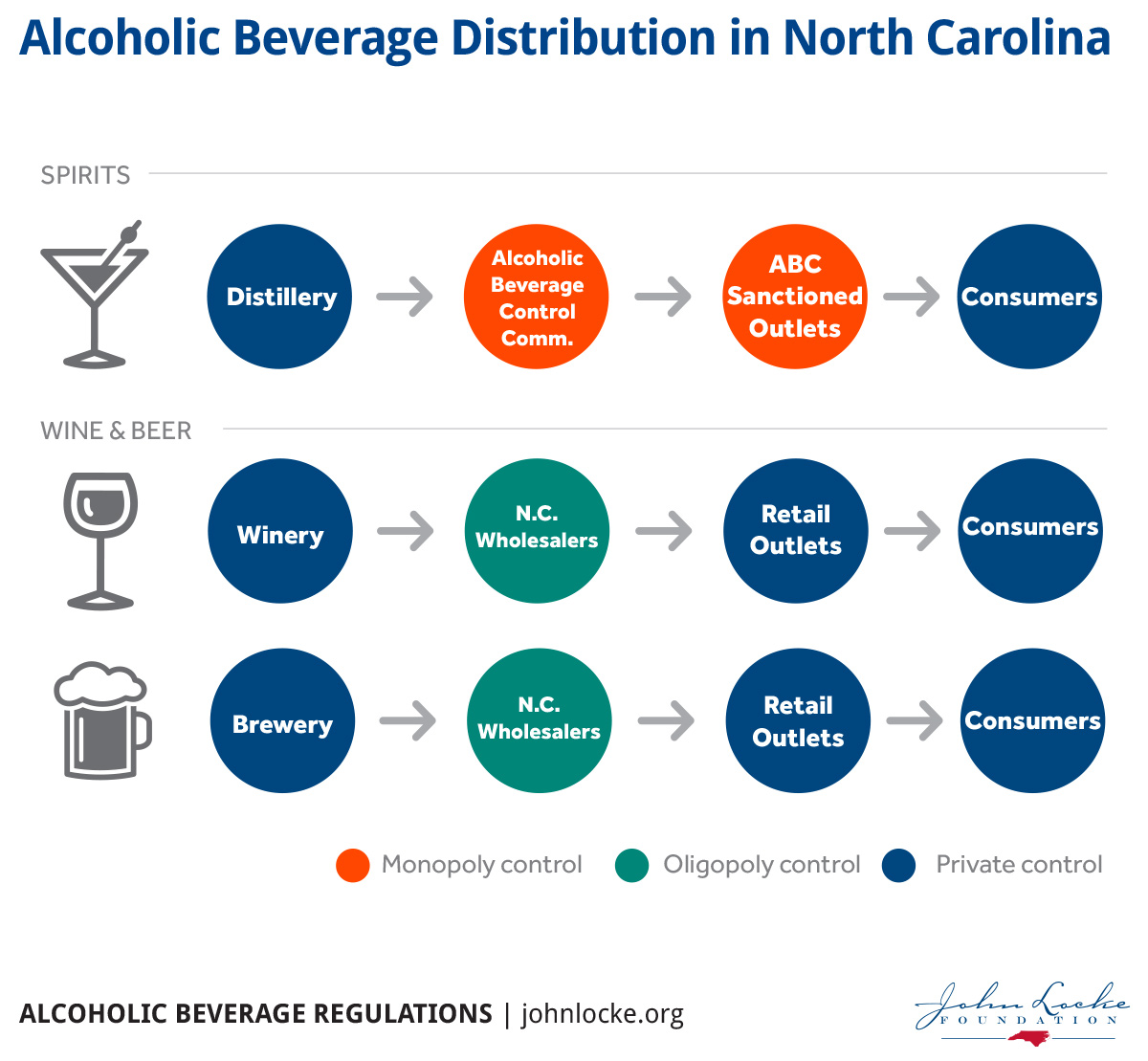

The state’s Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission (ABC) maintains a complete monopoly on the distribution of such liquor, and — with a few minor exceptions — such liquor may only be sold in stores owned and operated under the Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission’s authority.6 In short, the regulatory regime doesn’t just discourage entrepreneurs from entering this market; entering the market is a crime, and violators are subject to fines and incarceration.7

Of course, even the threat of criminal sanctions does not always stifle the entrepreneurial spirit completely. Robbie Delaney, who runs the Muddy River Distillery in Belmont, North Carolina, likes to point out that, whereas in Kentucky entrepreneurs created a billion-dollar industry based on the legal production of whiskey, in North Carolina entrepreneurs created a billion-dollar industry based on its illegal distribution.8 Where the threat of prosecution failed, however, a government enforced monopoly has succeeded. Bootleggers no longer dominate the liquor business the way they did in the days of NASCAR’s origins. Instead, the state-run Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission exercises virtually complete control over distribution and retail sales.

There is no public-interest justification for maintaining this state monopoly over the liquor business. The vast majority of states allow private businesses to distribute and sell liquor;9 yet the rate of alcohol related deaths and underage drinking are no higher in those states than they are in the 17 states that continue to monopolize the business.10

If it weren’t for the state monopoly, entrepreneurs would be operating hundreds of private liquor stores in North Carolina, and they would be competing for business with each other and with entrepreneurs operating thousands of grocery stores and other retail outlets. As it is, however, a limited number of ABC stores keep the same limited hours and charge the same artificially high prices for the same limited selection of products.11

The Wholesale Distribution Oligopoly

Unlike liquor, private companies are allowed to distribute and sell beer and wine in North Carolina, but the trade is tightly regulated in ways that discourage entrepreneurship. The biggest impediment to entrepreneurship is the system of wholesale distribution that is mandated by statute and administered by the Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission.12 While there are a small number of exceptions for small brewers and vintners, larger producers are not allowed to sell directly to retailers at all. Instead, they must deal with a limited number of licensed wholesale distributors who enjoy a profitable oligopoly on this trade. In addition to enriching the distributors at the expense of retailers and consumers, this expensive,

three-tier system of producer/distributor/retailer protects the big producers by giving small producers a powerful incentive to stay small.

A report in the Charlotte Business Journal vividly illustrates how this form of protectionism discourages entrepreneurship and inhibits economic growth:

The Olde Mecklenburg Brewery is walking away from its $130,000 investment in the Triad — just a year after expanding into that market.

The decision comes as Charlotte’s largest brewer inches closer to producing 25,000 barrels of beer this year. At that point, N.C law requires breweries to hand distribution over to a third-party. …

The law makes it frustrating, but necessary, to leave that market, says Ryan Self, director of sales.

“Every drop counts. It’s one of those laws of unintended consequences,” he adds. “It takes OMB from something that is growing every year as an employment and tax creator and puts us in a holding pattern.” …

OMB knows it will face difficult decisions as demand for its products continues to grow. “Our existing accounts sell more and more beer every year,” Self says. “We’ll have to pull back and say, ‘Who’s not getting beer this year?’”

It also limits the ability to create new varieties and seasonal brews. …

“It completely clips our wings as far as trying new things,” Self says.13

Speaking recently at a conference at Johnson and Wales University, OMB’s Ryan Self emphasized another reason why the brewing company is reluctant to exceed the 25,000 barrel-per-year threshold: turning its marketing over to the distribution cartel would mean firing 11 of its people.14

Other Regulations

The ABC monopoly and the wholesale distribution oligopoly are merely the most egregious elements of a vast regulatory regime. The chapter of the North Carolina General Statutes that deals specifically with the regulation of alcoholic beverages consists of 123 densely packed

pages, and there are many other alcoholic beverage regulations buried in other parts of the statute book.15 The chapters of the North Carolina Administrative Code that deal specifically with alcohol law enforcement and the Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission consist of 143 pages, and, again, there are other alcoholic beverage regulations buried in other chapters of the Code.16

Forty-three different types of permits and licenses are required for 43 different activities involving the sale of alcohol.17 In the case of a premise licensed to sell alcohol, a new permit is required for every change of ownership.18 Gambling devices are forbidden, as are premises with living quarters attached,19 and all licensed premises must adhere to a recycling plan approved by the ABC.20 There is a rule that forbids the owner of multiple premises from moving alcoholic beverages from one premise to another.21 There is a rule that restricts happy hours and forbids some kinds of drink specials,22 and another that forbids distilleries that offer tours from selling any specific visitor more than one bottle per year.23 There is a rule forbidding the sale of alcohol on public college campuses,24 and another stating that viticulture and enology may be taught only at colleges, universities, and community colleges.25 There are rules governing the content of ads for alcoholic beverages,26 rules governing the size of alcoholic beverages in hotel mini-bars,27 and rules governing the number of bottles or cans of beer in a “case.”28 There are rules governing how much alcohol a private citizen may possess and how much he or she may transport into the state.29 There are rules governing wine tastings.30 There is even a rule that forbids the sale of alcoholic beverages at bingo games.31

Making matters worse, this vast array of rules and regulations is administered by a variegated group of agencies that includes, not only the Alcoholic Beverage Control Commission and the Alcohol Law Enforcement Agency, but all the various state and local police forces. These agencies exercise a good deal of discretion in how they interpret and enforce the rules, which makes consistency impossible, compliance confusing, and abuse inevitable.

Dealing with this complex regulatory regime isn’t a problem for the large producers, distributors, and sellers. They have compliance officers and lawyers who are intimately familiar with the regulations — indeed, in many cases they helped write them — and they have long-standing relationships with the staff of the regulatory and enforcement agencies. For small-time entrepreneurs who want to enter the market for the first time, however, the regulatory regime constitutes a huge barrier. It’s very difficult for them to become familiar with the entire body of laws and rules, let alone acquire the expertise and contacts that are needed in order to deal effectively with all the relevant agencies. Some of them try and fail, and some of them never try at all.

Conclusion

Support for the existing system of alcoholic beverage regulation will undoubtedly remain strong in North Carolina. The “Baptists” — i.e., the concerned citizens — will continue to support the system because they believe (wrongly) that it protects society from the harms associated with alcohol abuse. The “Bootleggers” — i.e., the government bureaucrats, wholesale distributors, large brewers and distillers, and other interest groups that benefit from the regulations — will continue to support the system because they believe (rightly) that it protects their jobs, their power, their investments, and their profits.

Given this strong, ongoing support, it will not be easy to reform the stiflingly repressive regulatory regime that governs the production, distribution, and sale of alcoholic beverages in North Carolina. Nevertheless, there are some hopeful signs. A new generation of sophisticated consumers is demanding more variety and more quality when it comes to alcoholic beverages, and a new generation of entrepreneurs has emerged to serve them. The entrepreneurs, of course, are well aware that the existing regulatory regime protects the big companies at their expense, and they are starting to push back politically.32 More surprisingly, many of the consumers are also aware of the problem, and they too are becoming politically active.33 In short, there appears to be an emerging coalition of consumers and entrepreneurs that is willing and able to oppose the long-standing alliance of established businesses and concerned citizens.

Whether the beer lovers and brewers can be as effective in the future as the bootleggers and Baptists have been in the past remains to be seen. However, similar coalitions of consumers and entrepreneurs have had a number of notable successes with regard to federal Internet regulations and municipal ride-share regulations in recent years, and, perhaps more pertinently, similar coalitions have also had a number of notable successes with regard to alcoholic beverage regulations. In 2011, a coalition of consumers and entrepreneurs persuaded voters in Washington state to approve an initiative privatizing the state liquor monopoly;34 in 2012, a similar coalition persuaded the Connecticut legislature to repeal the state’s ban on Sunday sales;35 and just this year, yet another similar coalition persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn state laws banning the direct interstate shipment of wine to consumers.36 Let us hope North Carolina’s emerging coalition of beer lovers and brewers will turn out to be as effective as these other coalitions of consumers and entrepreneurs have been.

Alcoholic beverage regulations have stifled entrepreneurship in North Carolina for far too long. Privatizing the state-run liquor business, breaking up the state-enforced wholesale distribution oligopoly, and eliminating unnecessary and unreasonable rules would usher in a golden age for alcoholic beverages in North Carolina and move us significantly closer to the goal of being “first in freedom.”37

EndNotes

1. William P. Ruger and Jason Sorens, Freedom in the 50 States (Washington DC: Cato Institute, 2016), 220; http://www.freedominthe50states.org/overall/north-carolina.

1. Ibid., 75; http://www.freedominthe50states.org/alcohol/north-carolina.

2. Adam Smith and Bruce Yandle, Bootleggers and Baptists: How Economic Forces and Moral Persuasion Interact to Shape Regulatory Politics (Wash. D.C.: Cato Institute, 2014).

3. Ibid., vii-viii.

4. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-101(14).

5. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-800(a).

6. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-102.

7. Personal communication with Robbie Delaney, owner of the Muddy River Distillery, 1500 River Dr., Belmont, NC 28012.

8. According to the National Alcoholic Beverage Control Association, “Seventeen states … control the sale of distilled spirits … through government agencies at the wholesale level. Thirteen of those jurisdictions also exercise control over retail sales for off-premises consumption; either through government-operated package stores or designated agents.” http://www.nabca.org/States/States.aspx.

9. Michael LaFaive and Antony Davies, “Alcohol Control Reform and Public Health and Safety” (Mackinac for Public Policy, 2012).

10. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-802; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 8B-804; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-203(a)(5).

11. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-102.

12. Jennifer Thomas, Charlotte Business Journal, Jan. 29, 2016.

13. Classical Liberals of the Carolinas, Annual Meeting, Charlotte, N.C., Aug. 11, 2016.

14. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-100, et. Seq.

15. 14B N.C. Admin. Code 06A.0101, et. Seq.; 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15A.0101, et. Seq.

16. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-902(d).

17. 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15B.0108.

18. 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15B.0205; 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15B.0102(e).

19. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-902(h).

20. 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15B.0227.

21. 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15B.0223.

22. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-1005(a)(4).

23. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-1006(a).

24. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-1114.

25. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-105.

26. 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15A.1893; 14B N.C. Admin. Code 15B.0106.

27. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-1114.6(c).

28. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-304.

29. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-1001(15).

30. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 18B-308.

31. For example, Scott Maitland, whose Top of the Hill Restaurant in Chapel Hill was one of the first micro-breweries in North Carolina, has complained to the N.C. legislature about the negative impact that unreasonable regulations have had on his new TOPO micro-distillery. See, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dz6GIBK-jIw.

32. For example, a group of young moviemakers is attempting to crowd-fund a documentary called “Free Beer” that will call attention to the 25,000-barrel distribution cap and explain how it hurts the small, independent brewers that make the craft beer they love. See, http://www.freebeernc.com/about.

33. http://reason.org/news/show/washington-liquor-privatization.

34. http://www.ctbites.com/home/2012/5/17/blue-laws-officially-end-sunday-may-20th.html.

35. http://ij.org/press-release/ny-wine-latest-release/.

36. This Spotlight is adapted from a paper that was originally presented at the annual meeting of Classical Liberals of the Carolinas in Charlotte, N.C., on Aug. 11, 2016. Hunter Markson helped with the research when he was an intern at the John Locke Foundation in the summer of 2016.