Introduction

While the national health care policy debate focuses on access to health insurance and health providers, the importance of oral care often does not receive the attention it should. Oral health is much more than clean teeth. Gums, the lining of the mouth, tongue, lips, salivary glands, chewing muscles, nerves, and jaw bones are all components of full oral health.1 Research has shown a link between oral care and general health.2 Further, research on dental care has demonstrated that poor oral health care is associated with an increased rate of heart disease,3 poor self-esteem,4 and even poor quality of life.5 Access to oral care is essential for North Carolina’s complete health and well-being.

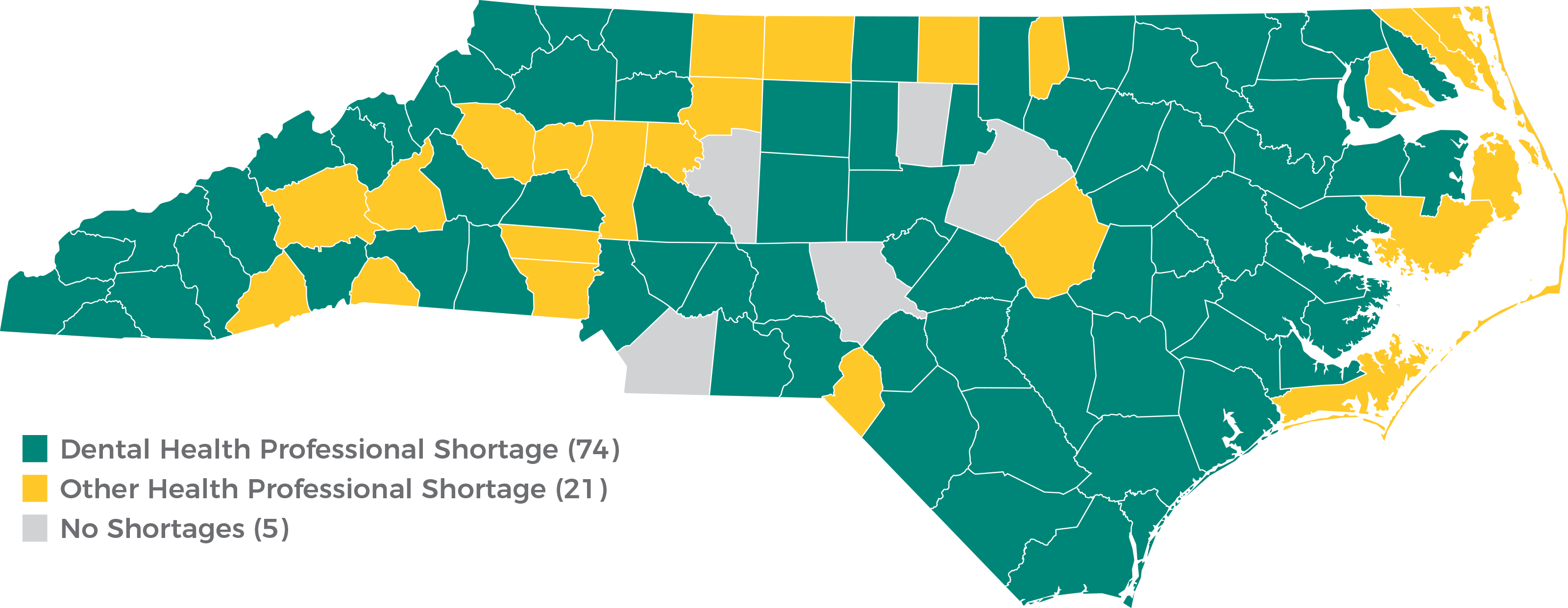

To determine where the number of health professionals is low in a state, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services designates Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs). Dental HPSAs are geographic areas, populations, or facilities for which the number of dental care providers is insufficient for serving the nearby population.6 As of December 31, 2018, North Carolina had 165 dental HPSA designations where over 2.5 million residents live.7 The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services reports that 74 of the state’s 100 counties are affected by dental professional shortages.8

The American Dental Association (ADA) projects that the supply of dentists will continue to increase through 2037.9 However, this trend does not mean that all of North Carolina’s populations will have access to the services they need. There are approximately 60.9 dentists per 100,000 people in the United States compared to 51.4 dentists per 100,000 people in North Carolina, ranking the state 37th in the country for provider-to-patient adequacy.10 Moreover, a report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services notes that 524 additional dental professionals are needed to remove North Carolina’s dental HPSA designations.11 While an increased number of dental professionals would alleviate the shortages in the state, the geographic distribution of providers and spectrum of available care models are also important factors in meeting the need for North Carolinians.

How can North Carolina address the need for more oral health options and increased provider adequacy? Mid-level dental practitioners, known as dental therapists, are proven effective in filling the gap with expertise and quality care in other states and around the world.12 Currently, North Carolina’s dental practice laws do not recognize the practice of dental therapy. The North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners would need to be given statutory authority to license dental therapists and recognize out-of-state dental therapy licenses. Giving North Carolinians access to this new class of professionals will help to increase access to crucial primary and restorative dental care across our state.

What are dental therapists?

Dental therapists are highly trained mid-level dental practitioners who provide basic preventive and restorative care under the supervision of a dentist. They are similar to physician assistants in general medicine. They first began practicing in New Zealand in 1921.13 Dental therapists practice in over 50 countries and territories across the globe.14 The first cohort of American dental therapists began practicing in 2005, serving Alaska Native communities throughout the state.15

Dental therapists’ scope of practice generally includes most of the same competencies maintained by dental hygienists, plus expertise in routine restorative procedures such as drilling and filling cavities, simple extractions, and stainless steel crowns.16, 17 Dental therapists are also trained in administering local anesthesia and nitrous oxide and can dispense non-narcotic pain relievers and antibiotics.18 Previously, only dentists were able to drill teeth. Thanks to the additional expertise offered by dental therapists, patients who once were forced to wait for an available dentist can now receive treatment faster and closer to home.

Dental therapists’ scope of practice generally includes most of the same competencies maintained by dental hygienists, plus expertise in routine restorative procedures such as drilling and filling cavities, simple extractions, and stainless steel crowns.16, 17 Dental therapists are also trained in administering local anesthesia and nitrous oxide and can dispense non-narcotic pain relievers and antibiotics.18 Previously, only dentists were able to drill teeth. Thanks to the additional expertise offered by dental therapists, patients who once were forced to wait for an available dentist can now receive treatment faster and closer to home.

Dental therapists can go where dentists are scarce and in more convenient locations for patients, such as rural clinics, nursing homes, schools, and programs for people with disabilities. Because dental therapists earn significantly less than dentists, it is more affordable for practices to send them to underserved areas.

Dental therapists’ lower wages also make it less expensive for practices to treat Medicaid patients, and more feasible for dentists to accept Medicaid.

State dental practice laws and licensure regulations determine the scope of practice, supervision requirements, and education and training requirements for dental therapists. Scope of practice is mostly consistent between states, but education and training requirements vary. For instance, in Minnesota, dental therapists must hold at least a bachelor’s degree from an accredited dental therapy program, while Alaskan dental therapists need only an associate degree.19, 20

Critical to the effectiveness of dental therapists is a reasonable and limited regulatory environment. Most state dental therapy laws allow them to perform a large portion of their scope of practice under general supervision. That means a supervising dentist is not required on the premises where services are performed.21, 22, 23 This allows dental therapists to travel outside their home dental offices and treat patients where the need exists. According to the Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota Board of Dentistry, “General supervision of [advanced dental therapists] has made it economically viable for dental clinics to provide routine dental care in schools, rural communities, Head Start programs, nursing homes, and other community settings. It also makes it possible for a dental clinic to provide services at times when a dentist is not on site.”24

Which states are leading the way?

As of April 2019, 10 states allow dental therapists to practice. Arizona, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, and Vermont authorized dental therapists to practice statewide.25, 26, 27, 28, 29 In Alaska, Idaho, Oregon, and Washington, dental therapists may only practice in tribal communities.30, 31, 32, 33 Alaskan dental therapists serve native communities under federal authority as part of the Indian Health Service’s Community Health Aide Program.34

While 10 states allow, to some capacity, the practice of dental therapists, only four states currently have dental therapists practicing on the ground.35 It takes time to transition from the legal authority phase to the service-delivery phase. Once a state passes legislation to create a license for dental therapists, educational institutions must develop curriculum and seek accreditation from the Commission on Dental Accreditation. Then, the educational institutions must recruit and train their first class of dental therapists, the timeline for which depends on the education and training requirements passed by the state. States that require dental therapists to hold a master’s degree will wait longer to see their dental therapy workforces grow than states like Alaska, where therapists need only to wait approximately two years before practicing.

Minnesota has the largest number of practicing dental therapists – 93 as of April 201936 – and trains roughly 14 new dental therapists each year.37, 38 Alaska had over 30 dental therapists on the ground as of September 2018 and trains six new dental therapists each year.39 Washington and Oregon each have two dental therapists, with five Washington-based students and four Oregon-based students currently being trained in Alaska.40 The Vermont Technical College has designed curriculum and is in the process of pursuing accreditation before launching Vermont’s first dental therapy program.41, 42 Arizona and Michigan passed dental therapy legislation in 2018, and New Mexico in 2019, and colleges in these states have already expressed interest in developing training programs.43 Needless to say, the dental therapy workforce is growing rapidly in the U.S. and more states are considering legislation to get the ball rolling.44

How would North Carolina begin?

States can introduce dental therapists into their communities by passing legislation to establish, recognize, and regulate dental therapy licenses, typically accomplished by adding a section to a state’s occupations code and requiring the state’s dental board to make corollary changes. In North Carolina, this would involve adding an Article to Chapter 90 (Medicine and Allied Occupations) of General Statutes and authorizing the North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners to oversee licensure.

Lessons learned: Positive effects of dental therapy in Alaska and Minnesota

Dental therapists have been practicing in Alaska for over a decade, longer than in any other state.45 In October 2010, five years after dental therapists had been introduced to Alaska Native communities, RTI International (RTI) published an evaluation of this workforce. It found that people in communities served by dental therapists experienced increased access to care, including reduced wait times.46 Those who were treated by a dental therapist were generally very satisfied with the quality of care and viewed the practitioners as positive role models.47 The evaluation found the observed dental therapists to be technically competent and even comparable to dentists when performing basic restorations.48 Overall, the Alaskan dental therapists “perform[ed] well and operat[ed] safely and appropriately within their defined scope of practice.”49

University of Washington faculty published the first long-term study of Alaskan dental therapists in August 2017. They found that more children and adults received preventive care in communities with high dental therapist treatment days, i.e., days for which a dental therapist provided care.50 These communities also had fewer young children with front-tooth extractions and fewer adults with permanent-tooth extractions.51 These results suggest that the introduction of dental therapists to Alaska Native Communities is having a long-term, positive impact on patient health outcomes.

According to the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium (ANTHC), dental therapists have expanded access to care for over 40,000 Alaskan Natives in 81 rural communities.52 In 2017, ANTHC partnered with Iḷisaġvik College, Alaska’s only Tribal College, to offer an associate degree in dental therapy.53 Increasing investment in education programs for dental therapists in Alaska is a testament to their success.

Minnesota licensed its first dental therapist in 2011 and currently has the largest number of practicing dental therapists in the country.54, 55 In February 2014, the Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota Board of Dentistry produced a report on the “Early Impacts of Dental Therapists in Minnesota.” It found that dental therapists at 14 observed clinics treated over 6,000 new patients, 84 percent of whom had public health insurance.56 One third of surveyed patients experienced lower wait times and some experienced reduced travel times, especially those in rural areas.57 Surveyed clinics employing dental therapists experienced personnel cost savings, increased dental team productivity, and improved patient satisfaction.58 Overall, clinics found that utilizing a dental therapist allowed them to treat more underserved patients.59

In February 2017, a “Dental Therapy Toolkit” was produced for the Minnesota Department of Health by the in-state colleges with dental therapy programs. The toolkit is an extensive resource for potential employers of dental therapists. According to the toolkit, “Nearly all Minnesota’s [dental therapist] employers have found [dental therapists] to be a financially beneficial addition to their dental teams.”60 The main reasons cited are that dental therapists are cheaper to employ than dentists, they increase team productivity and efficiency, and they free up dentists’ time to focus on more complex, highly-reimbursed procedures.61 This combination of savings enables practices to provide more care with available resources and creates the potential for patient savings.

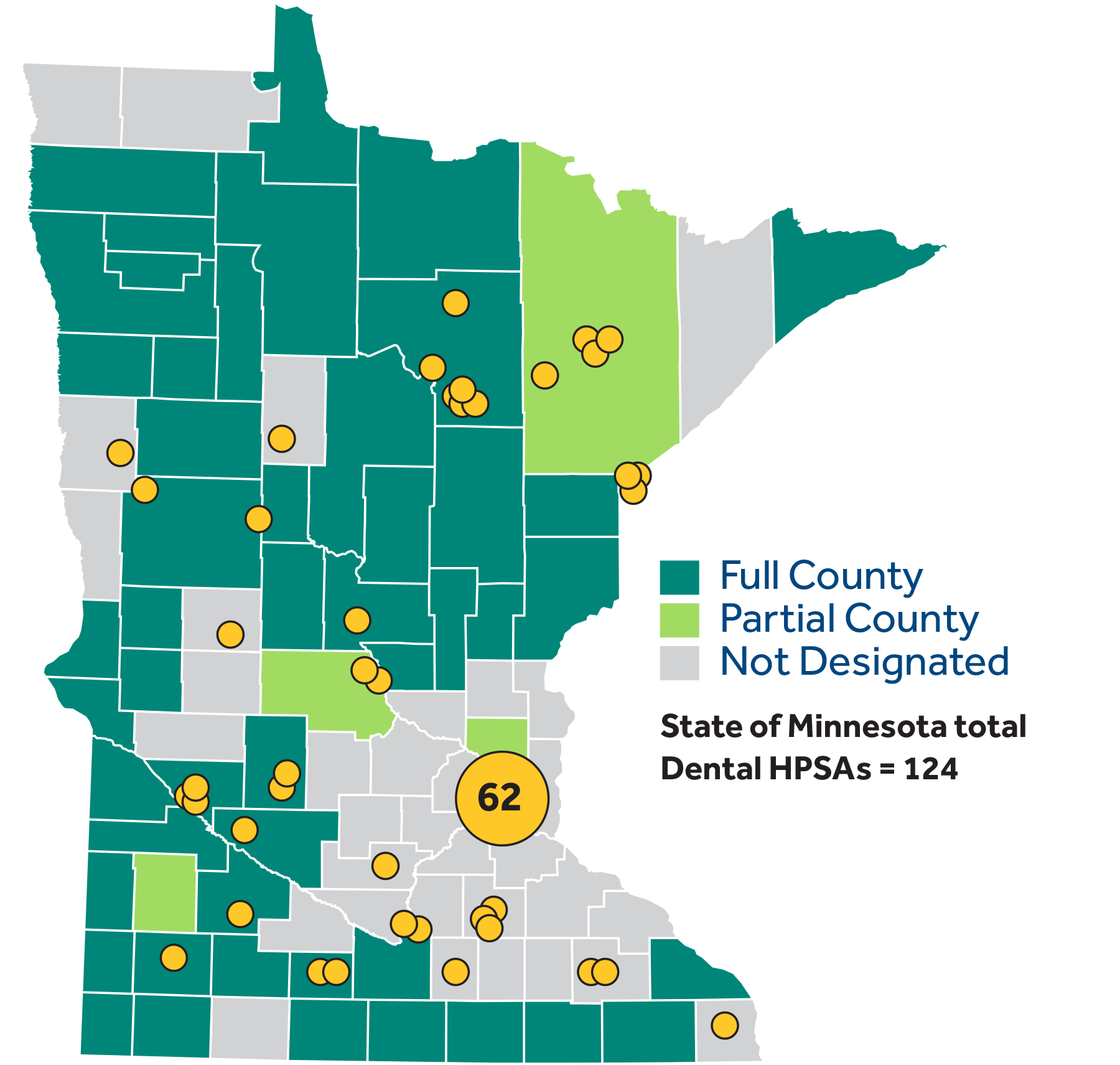

The Minnesota Department of Health and the Minnesota Board of Dentistry continue to acknowledge the positive effects of dental therapy in a 2018 issue brief, which summarizes findings since 2011. The brief states that dental therapists are distributed proportionately to the state population, with over 40 percent practicing in non-metropolitan areas.62 Minnesota dental therapists have a high rate of employment (93 percent) in a variety of settings, including “schools, Head Start programs, community centers, [Veterans Affairs] facilities and nursing homes.”63 They provide services in community and rural settings at more than 370 mobile dental sites throughout the state.64 Furthermore, 98 percent of dental therapists are satisfied with their careers and 84 percent plan to practice for at least a decade.65 Figure 1 illustrates where dental therapists practice in Minnesota relative to dental HPSAs in November 2018.66 Note that the map does not portray the many mobile sites where dental therapists practice.

Figure 1. Minnesota Dental Health Professional Shortage Areas, 2018

Source: University of Minnesota School of Dentistry, “Dental Therapists in Practice by Health Professional Shortage Areas”

Minnesota Medicaid reimbursements are based on procedures, rather than practitioners, so the state has seen no public-fund savings in the short term.67 However, the Minnesota Department of Health anticipates long-term public-fund savings through improved oral health and reduced dental-related emergency room visits among patients with public health insurance.68 Remarkably, almost no public funds have been spent to support the dental therapy workforce, except initially in some high-need areas.69 The demand for, and growth of, dental therapists is, for the most part, organic and patient-driven.

The evidence suggests that dental therapists stand to benefit all parties within the dental care delivery system. A wide variety of practice settings see higher productivity and revenue, dentists are enabled to practice more complex and highly-reimbursed procedures, and dental hygienists and assistants can gain a new career option. Further, states could save money or increase dollar efficiency in the long run through reduced dental-related emergency room visits. Most importantly, patients experience improved access to care without sacrificing quality and safety.

The need for more dental care in North Carolina

Insufficient supply and cost are the two main barriers that many populations in North Carolina face when it comes to receiving the appropriate oral care. The lack of proper oral health disproportionately affects those in rural parts of the state, the American Indian population, low-income residents, children, and the elderly. In addition, North Carolina has over 2 million enrollees in the Medicaid program, which offers generous child and adult dental benefits compared to other states.70 However, the fact that dentists in a particular area may not accept Medicaid as insurance or may not be accepting new Medicaid patients can exacerbate the problems of dental professional shortages. Increasing the supply of dental therapists could help address the access and financial barriers that these underserved communities face by increasing both the supply of dental care professionals and lowering the cost through enhanced competition among providers.

Rural Population

As of the 2010 census, North Carolina’s rural population was 3,233,727, ranking the state second behind Texas in total rural population.71 According to the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Rural Health, a substantial portion of the state lacks the proper supply of primary care physicians, dental professionals, or mental health professionals. The agency has designated 59 counties as having a shortage of primary care physicians, mental health professionals, and dental professionals.

Figure 2. N.C. Dental Health Professional Shortage Areas

Source: NC Department of Health and Human Services Office of Rural Health, “North Carolina Counties Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas SFY 2018”

In addition to having fewer providers to choose from, many individuals living in rural areas may have a difficult time affording dental care.72 Data compiled by the North Carolina Chamber of Commerce show that, as of 2017, median income in rural counties tended to be lower than urban and suburban counties.73 Research also shows that rural populations tend to utilize dental care at a lower rate than other communities.74 Reasons vary. In many cases, costs of dental care present a significant barrier.75 In other cases, the dentist’s office is located far away, which patients may not be able to access, or individuals may lack awareness about the importance of oral health.76 Dental therapists can help fill this treatment gap. In countries and states where dental therapy is permitted, these mid-level practitioners have been shown to serve rural and underserved populations.77 Not only are dental therapists cost-effective practitioners, they can also increase the patient volume of existing dental practices by providing routine preventive and restorative care, which can increase the financial stability of practices in rural areas.78

American Indian Population

Not only is North Carolina’s population unique due to its high number of rural residents, but the state has the highest American Indian population east of the Mississippi.79 According to a report released by North Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities, American Indians experience significant health problems, mostly due to limited access to health professionals in rural counties, where they tend to live.80 Further, North Carolina’s American Indian children are almost twice as likely to enter kindergarten with tooth decay compared to non-Hispanic white children.81 This population would likely benefit from having access to dental therapists that are allowed to travel and deliver care outside their home dental offices.

Children and Medicaid Population

Proper oral health is especially important for children. If issues aren’t addressed early in a child’s life, they can persist and become costly.82 Inadequate oral care can also affect a child’s ability to learn, the likelihood of attending class, and academic outcomes.83 Children from low-income families are twice as likely to have untreated tooth decay compared to those from high-income families.84 According to a study from the Oral Health Section of the Department of Health and Human Services in North Carolina, 14.3 percent of all kindergarten children have untreated tooth decay.85 While this is lower than the national average of 20 percent, North Carolina should embrace its leadership in this area and push this number closer to zero through increased access to oral care.

Children insured by Medicaid are less likely to have an annual dentist visit than children with private insurance, even though kids covered by Medicaid have dental care as a benefit. According to Medicaid data, in 2017, 1,329,341 North Carolina Medicaid recipients under the age of 21were eligible for dental services, yet only 654,667 received care. This means a substantial number of children went the entire year without any dental services. Additionally, in 2016, only 29.7 percent of dentists participated in Medicaid compared to the national average of 39 percent.86 It’s important to note that dentist participation reflects only enrollment rates; some dentists who enroll do not actually serve Medicaid patients and/or do not accept new Medicaid patients. Thus, the Medicaid population has difficulty finding a dentist that accepts Medicaid as payment. By creating a more abundant supply of cost-effective mid-level practitioners — dental therapists — Medicaid patients could have greater access to affordable care.

Older Adults

By 2035, 1 in 5 North Carolina residents will be 65 or older. Research on the condition of the elderly population’s dental health has shown that, more often than not, a person in this age group needs some form of dental treatment.87, 88 Seniors are more likely to have gum disease. When compared to white seniors, African-American seniors are twice as likely to either have untreated tooth decay or gum disease.89 Increasing the number of practitioners who can perform routine restorative care — a treatment which would be heavily utilized by the elderly population — would significantly improve seniors’ oral health. This is a crucial point due to the growth of the senior demographic.

Hospital Emergency Room Visits

Dental care and state health care costs are more entangled than most may realize. When someone has a dental emergency, and there is little or no access to qualified personnel, the emergency room may be the only place to seek treatment. However, the emergency room is one of the most expensive locations to receive care.90 What’s more, emergency rooms are often not equipped to treat dental problems, offering only medication to control pain and infection.91 North Carolina has an alarming trend of high dental-related visits to the emergency room in recent years, more than twice the amount in our neighboring states and far above the national average. 92

Addressing preventive and restorative oral health issues at an early age could result in lower emergency room utilization. As previously noted, a sizable number of rural residents rely on Medicaid for health insurance. North Carolina could run a more cost-efficient Medicaid program over time from the introduction of dental therapists because of lower costs due to better oral health in the long term, as well as a lower utilization rate of emergency rooms.

Conclusion

The data shows that dental professionals in North Carolina are in short supply and unevenly distributed for many areas in the state. Furthermore, the cost of dental care can present a barrier for low-income individuals. Given these problems with access, many individuals in the state do not receive the proper dental care they need. As research has shown, there is a demonstrated link between oral health and overall health. Many of the underserved populations in the state such as rural residents, those with low income, American Indian populations, children, and the elderly are disproportionately affected by the lack of access to oral care.

Health care reform in North Carolina should focus on embracing market-oriented solutions to provide for the demand in the state. Lawmakers could begin to address the need for greater access to oral care by creating the opportunity for dental therapists to practice. The experiences of other states that allow this profession show that these dental professionals could help bridge the gap for many who face significant barriers to proper oral care. While this policy solution would not solve the state’s oral health issues in totality, creating an environment which allows the practice of dental therapy would increase the number of practitioners who specialize in the sort of care that North Carolina’s underserved populations need. Allowing the practice of dental therapy is a reasonable supply-side reform to increase access to essential oral care in the state.

Endnotes

- Benjamin, Regina M. “Oral Health: The Silent Epidemic.” Oral Health: The Silent Epidemic 125, no. 2 (March 1, 2010): 158-59. doi:10.1177/003335491012500202.

- Imai, Satomi, and Christopher Mansfield. “Oral Health in North Carolina: Relationship With General Health and Behavioral Risk Factors.” North Carolina Medical Journal 76, no. 3 (July 2015) 142-47. doi:10.18043/ncm.76.3.142.

- Montebugnoli, L., D. Servidio, RA Miaton, C. Prati, and C. Melloni. “Poor Oral Health Is Associated with Coronary Heart Disease and Elevated Systemic Inflammatory and Haemostatic Factors.” Journal of Clinical Periodontology 31, no. 1 (January 2004): 25-29. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15058371.

- Benyamini, Yael, Howard Leventhal, and Elaine A. Leventhal. “Self-rated Oral Health as an Independent Predictor of Self-rated General Health, Self-esteem and Life Satisfaction.” Social Science & Medicine 59, no. 5 (September 2004): 1109-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.021.

- Locker, D., M. Clarke, and B. Payne. “Self-perceived Oral Health Status, Psychological Well-being, and Life Satisfaction in an Older Adult Population.” Journal of Dental Research 79, no. 4 (April 2000): 970-75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00220345000790041301.

- Ryan, Melissa. “Health Professional Shortage Areas and Scoring.” Health Resources and Services Administration. June 22, 2016. https://nhsc.hrsa.gov/downloads/nacnhsc/advisory-council-meeting-June-2016-health-professional-shortage-areas-scoring.pdf

- United States. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://ersrs.hrsa.gov/ReportServer?/HGDW_Reports/BCD_HPSA/BCD_HPSA_SCR50_Qtr_Smry_HTML&rc:Toolbar=false.

- “North Carolina Counties Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas SFY 2018.” North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. https://files.nc.gov/ncdhhs/2018%20NC%20DHHS%20ORH%20HPSA%20One%20Pager_0.pdf.

- Munson, Bradley, and Marko Vujicic. Issue Brief. July 2018. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science and Research/HPI/Files/HPIBrief_0718_1.pdf?la=en.

- “Dentists in North Carolina in 2018.” America’s Health Rankings. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/dentists/state/NC.

- United States. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://ersrs.hrsa.gov/ReportServer?/HGDW_Reports/BCD_HPSA/BCD_HPSA_SCR50_Qtr_Smry_HTML&rc:Toolbar=false.

- Nash, DA, JW Friedman, and KR Mathu-Muju. “A Review of the Global Literature on Dental Therapists.” Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 42, no. 1 (February 2014): 1-10. doi:10.1111/cdoe.12052.

- Nash, David A., Jay W. Friedman, and Kavita R. Mathu-Muju. A Review of the Global Literature on Dental Therapists. Literature Review. April 10, 2012. https://www.wkkf.org/resource-directory/resource/2012/04/nash-dental-therapist-literature-review. (pg. 2).

- Ibid. (pg. 351)

- Chi, Donald L., Dane Lenaker, Lloyd Mancl, Matthew Dunbar, and Michael Babb. Dental Utilization for Communities Served by Dental Therapists in Alaska’s Yukon Kuskokwim Delta: Findings from an Observational Quantitative Study. Report. School of Dentistry, University of Washington. August 11, 2017. http://faculty.washington.edu/dchi/files/DHATFinalReport.pdf. (Pg. 2)

- Community Health Aide Program Certification Board Standards And Procedures. Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. Alaska Community Health Aide Program. January 25, 2018. http://www.akchap.org/html/chapcb.html. (Pg. 33-34)

- Dental Therapist, 2018 Minnesota Statutes § 150A.105-Subd. 4 (2009). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/150A.105.

- Dental Therapist, 2018 Minnesota Statutes § 150A.105-Subd. 5 (2009). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/150A.105.

- Licensure, 2018 Minnesota Statutes § 150A.06-Subd. 1d (2009). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/150A.06.

- Dental Health Aide Therapist (DHAT) Educational Program. PDF. Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. http://anthc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/DHAT_Curriculum.pdf.

- Dental Therapist, 2018 Minnesota Statutes § 150A.105-Subd. 4 (2009). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/150A.105.

- Dental therapists; clinical practice; supervising dentists; written collaborative practice agreements, Arizona Revised Statutes § Chapter 11-32-1276.04 (2018). https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https://www.azleg.gov/ars/32/01276-04.htm.

- Practice; scope of practice, Vermont Statutes § Title 26-12-613 (2018). https://legislature.vermont.gov/statutes/section/26/012/00613.

- Minnesota Department of Health. Dental Therapy in Minnesota. June 12, 2018. https://www.health.state.mn.us/data/workforce/oral/docs/2018dtb.pdf.(Pg. 3)

- Licensing and Regulation of Dental Therapists, Arizona Revised Statutes § Title 32-11-3.1 (2018). https://www.azleg.gov/arsDetail/?title=32.

- Dental hygiene therapist, Maine Revised Statutes § Title 32-143- 18377 (2018). http://legislature.maine.gov/legis/statutes/32/title32sec18377.html.

- Dental therapist; scope of practice; within certain health settings, Michigan Compiled Laws § Chapter 333-16654 (2018). http://www.legislature.mi.gov/(S(mvoczyu2jf2enok3jm2wfpfr))/mileg.aspx?page=getObject&objectName=mcl-333-16654)

- Dental Therapist, 2018 Minnesota Statutes § 150A.105 (2009). https://www.revisor.mn.gov/statutes/cite/150A.105.

- Practice; scope of practice, Vermont Statutes § Title 26-12-613 (2018). https://legislature.vermont.gov/statutes/section/26/012/00613.

- Authorization—Conditions, Revised Code of Washington § Chapter 70-350.020 (2018). https://app.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=70.350.020.

- “RE: Dental Pilot Project Application #100, “Oregon Tribes Dental Health Aide Pilot Project,” Approval with Addendum.” Bruce W. Austin to Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board. February 8, 2016. In Oregon Tribes Dental Health Aide Therapist Pilot Project. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PREVENTIONWELLNESS/ORALHEALTH/DENTALPILOTPROJECTS/Documents/100-approval.pdf.

- “About the Alaska CHAP Program.” Alaska Community Health Aide Program. http://www.akchap.org/html/about-chap.html.

- HB 308, New Mexico 2019 Regular Session, https://www.nmlegis.gov/Legislation/Legislation?Chamber=H&LegType=B&LegNo=308&year=19.

- Wetterhall, Scott, James D. Bader, Barri B. Burrus, Jessica Y. Lee, and Daniel A. Shugars. Evaluation of the Dental Health Aide Therapist Workforce Model in Alaska. RTI International. RTI International. October 2010. https://www.rti.org/sites/default/files/resources/rti-publication-file-3238755a-51bc-4e10-b2a1-74c28deec2b6.pdf. (Pg. ES-1)

- Koppelman, Jane. “Dental Therapy: A Workforce Option to Improve Access to Oral Health Care in Wisconsin.” Children’s Health Alliance of Wisconsin, September 26, 2018. https://www.chawisconsin.org/download/koppelman-presentation-panel-page/?wpdmdl=2074&refresh=5cd0ac88dc1951557179528.

- Active Licensee Totals, Minnesota Government, 2 May 2019, mn.gov/boards/assets/ActiveAll%2005-02-19_tcm21-383260.pdf.

- Koppelman 2018. (Pg. 19)

- Dental Therapy in Minnesota. (Pg. 4)

- Koppelman 2018. (Pg. 19)

- Ibid. (Pg. 20)

- Vermont Technical College. “Vermont Dental Therapy Education Program Moves Forward.” News release, June 28, 2017. Vermont Tech. https://www.vtc.edu/news/vermont-dental-therapy-education-program-moves-forward.

- Warren, Cheyanne. “Phone Conversation with Dr. Cheyanne Warren, Dental Therapy Program Director, Vermont Technical College.” Telephone interview by Jennifer Minjarez. January 2018.

- David L. Eisler to The Honorable Mike Shirkey. November 30, 2018. Letter of support for dental therapy legislation, from Ferris State University Office of the President, digital file available upon request to authors.

- Koppelman, Jane. “States Expand the Use of Dental Therapy.” Pew. January 23, 2019. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2016/09/28/states-expand-the-use-of-dental-therapy.

- Chi et al. (Pg. 2)

- Wetterhall et al. (Pg. ES-3)

- Ibid. (Pg. ES-3)

- Ibid. (Pg. ES-3)

- Ibid. (Pg. ES-4)

- Chi et al. (Pg. 2)

- Ibid. (Pg. 2)

- “Alaska Dental Therapy Educational Programs.” Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. https://anthc.org/alaska-dental-therapy-education-programs.

- Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. “Dental Health Aide Therapy Training Program Becomes a Degree Program, Gains Financial Aid Eligibility and Comes Home to Alaska in 2017.” News release, June 3, 2016. https://anthc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/2016-06-06-DHATProgramChanges.pdf.

- Minnesota Department of Health and Minnesota Board of Dentistry. Early Impacts of Dental Therapists in Minnesota. February 2014. https://www.health.state.mn.us/data/workforce/oral/docs/dtlegisrpt.pdf (Pg. 1)

- Koppelman 2018. (Pg. 19-20)

- Early Impacts. (Pg. 1)

- Ibid. (Pg. 1)

- Ibid. (Pg. 2)

- Ibid. (Pg. 2)

- Dental Therapy Toolkit: A Resource for Potential Employers. Report. University of Minnesota School of Dentistry, Metropolitan State University/Normandale Community College, and MS Strategies. February 2017. https://www.health.state.mn.us/facilities/ruralhealth/emerging/dt/docs/2017dttool.pdf. (Pg. 52)

- Ibid. (Pg. 52)

- Dental Therapy in Minnesota. (Pg. 4)

- Ibid. (Pg. 4)

- Ibid. (Pg. 4)

- Ibid. (Pg. 4)

- Dental Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) Designations, 2018. PDF. University of Minnesota School of Dentistry, November 2018. https://www.dentistry.umn.edu/sites/dentistry.umn.edu/files/dt_plot_map_november_2018.pdf.

- Dental Therapy in Minnesota. (Pg. 3)

- Ibid. (Pg. 3)

- Ibid. (Pg. 3)

- Haney, Kevin. “Does Medicaid Cover Dental Work for Adults.” Growing Family Benefits. July 26, 2018. https://www.growingfamilybenefits.com/medicaid-cover-dental-work/.

- United States. Census Bureau. March 26, 2012. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb12-50.html.

- Way, Dan. “Remote Corners of N.C. Face Dental-care Shortage; Lawmakers Take Note.” Carolina Journal, June 11, 2018. https://www.carolinajournal.com/news-article/remote-corners-of-n-c-face-dental-shortage-lawmakers-taking-note/.

- “NC County Profile Data.” Demographic Reports. 2017. https://accessnc.nccommerce.com/DemographicsReports/.

- Skillman, SM, MP Doescher, WE Mouradian, and DK Brunson. “The Challenge to Delivering Oral Health Services in Rural America.” Journal of Public Health Dentistry 70, no. 1 (June 2010): 49-57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20806475.

- Vujicic, Marko, Thomas Buchmueller, and Rachel Klein. “Dental Care Presents The Highest Level Of Financial Barriers, Compared To Other Types Of Health Care Services.” Health Affairs. December 2016. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0800?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub=pubmed.

- “Barriers to Oral Healthcare in Rural Communities.” Rural Health Information Hub. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/oral-health/1/barriers.

- Lopez Bauman, Naomi, and John Davidson. The Reform That Can Increase Dental Access and Affordability in Arizona. Publication. https://goldwaterinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/cms_page_media/2017/4/10/Dental Access Reform_Final.pdf.

- Koppelman, Jane. “Dental Therapists Can Provide Cost-Efficient Care in Rural Areas.” Pew Trusts. March 12, 2018. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2018/03/12/dental-therapists-can-provide-cost-efficient-care-in-rural-areas.

- “Native American Population by State 2017.” World Population Review. http://worldpopulationreview.com/states/native-american-population/.

- Bell, Ronny A., and Mark E. Moss. “Oral Health Disparities Among NC’s American Indian Population.” The Road to Oral Health Equity in North Carolina 1 (September 2018): 4.

- Rozier, R. Gary. Portrait of Oral Health in North Carolina. Report. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9yd_cH0xazsNmpvakxPTEdzMTA/view (pg. 17)

- Otto, Mary. “How Can a Child Die of Toothache in the US?” The Guardian. June 13, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/jun/13/healthcare-gap-how-can-a-child-die-of-toothache-in-the-us.

- Virdine, Sarah, and Abby Hamrick. Https://www.ncchild.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/FINAL-Oral-Health-Report.pdf. Report. 2.

- Ibid. Pg. 1

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health NC. https://publichealth.nc.gov/oralhealth/docs/OralHealthSnapshots-NC-120718.pdf.

- “Dentist Participation in Medicaid or CHIP.” American Dental Association. 2016. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science and Research/HPI/Files/HPIGraphic_0318_1.pdf?la=en.

- Theresa Montini et al., “Barriers to Dental Services for Older Adults,” American Journal of Health Behavior 38, no. 5 (September 2014): 781–8, http://dx.doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.38.5.15.

- Tippett, Rebecca. “NC in Focus: Population Proportion 65 and Older, 2010-2035.” Carolina Demography. May 14, 2015. https://demography.cpc.unc.edu/2015/05/14/nc-in-focus-population-proportion-65-and-older-2010-2035/.

- “Older Americans Need Better Access to Dental Care.” Pew Trusts. July 21, 2016. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2016/07/older-americans-need-better-access-to-dental-care.

- Kliff, Sarah. “Emergency Room Are Monopolies. Patients Pay the Price.” Vox. December 4, 2017. https://www.vox.com/health-care/2017/12/4/16679686/emergency-room-facility-fee-monopolies.

- Okunseri, Christopher, Raymond A. Dionne, Sharon M. Gordon, Elaye Okunseri, and Aniko Szabo. “Prescription of Opioid Analgesics for Nontraumatic Dental Conditions in Emergency Departments.” Drug Alcohol Dependence, no. 156 (November 1, 2015): 261-66. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.09.023.

- Rozier, R. Gary. Portrait of Oral Health in North Carolina. Report. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B9yd_cH0xazsNmpvakxPTEdzMTA/view (pg. 16)