In 2013 President Barack Obama joined Democrats in Congress pushing for an increase of the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour.1 Such an increase of $2.85 per hour would have been a sizeable boost (39 percent) over the current minimum wage of $7.25 per hour.

In 2015 they upped their call to a $12 per hour minimum wage.2 Some state Senate Democrats in North Carolina urged the same here.3 More recently, liberal politicians, media, and activists have demanded the minimum wage be $15 per hour on the basis of “faith and morality”4 and to “boost the economy” and put “more workers in the active economy.”5

At the same time a small handful of cities across the nation implemented steps toward a $15 per hour minimum wage. In 2016 the General Assembly prevented cities from taking such action in North Carolina6 as part of its state constitutional oversight of local government.7

Although advocates believe such a massive increase in the minimum wage would help the economy and employment, economic research consensus finds that the effect of increasing the minimum wage on employment is negative. Furthermore, raising the minimum wage has the bitter unintended consequence of putting the very people out of work that well-intentioned supporters think it would help: the poorest, the least skilled, and the disadvantaged.

The bigger the hike, the more painful the toll on the most vulnerable workers.

The consequences in North Carolina of hiking the minimum wage would be negative and potentially very large, depending on how big the increase.

Economic research consensus: higher wages for some, job losses for others

In 2006, economists David Neumark and William Wascher published a Working Paper at the National Bureau of Economic Research surveying the economic literature on minimum wages. Among their findings:

- Negative employment effects was a “relatively consistent” finding — especially from “almost all” of the studies providing the “most credible evidence”

- Conversely, “very few — if any” studies provided “convincing evidence of positive employment effects”

- There was “relatively overwhelming evidence of stronger disemployment effects” for the least-skilled8

In 2013 and 2014 Neumark and Wascher, joined by economist J.M. Ian Salas, revisited the issue in light of new studies. They concluded that “the evidence still shows that minimum wages pose a tradeoff of higher wages for some against job losses for others, and that policymakers need to bear this tradeoff in mind when making decisions about increasing the minimum wage”9 and that “the best evidence still points to job loss from minimum wages for very low-skilled workers — in particular, for teens.”10

The last large increase in the federal minimum wage was from $5.15 to $7.25 per hour (nearly 41 percent), a stepwise increase that started in July 2007 and concluded in July 2009.11

In 2014 economists Jeffrey Clemens and Michael Wither looked at how that increase affected low-skilled workers’ employment and income trajectories. They found it “had significant, negative effects on the employment and income growth” for low-skilled workers.12

A lower income trajectory is the result of the higher minimum wage keeping low-skilled workers from accumulating experience as well as income, artificially limiting their upward income mobility, even to rise just to the lower middle class.

Looking at 2009 data for teenagers, Algernon Austin, director of the race, ethnicity and the economy program at the Economic Policy Institute, found that

In 2009, teens from poor families were less likely to find work than their middle-class peers. Poor African American teens, however, were the worst off: Only 20% were able to find work, compared with 31% of poor Hispanic teens and 36% of poor white teens.13

In North Carolina, that increase caused a 3.6 percent employment decline among teenagers — but for teens without 12 years of education, the decline was much higher: 7.2 percent.14

In five years, employment of teenagers nationally had fallen by 10 percentage points. A Today/Reuters analysis in 2012 found that the teens hardest hit were also “those who may need the money most: teens from poor families in which a parent is out of work.”15 Least affected: teens from wealthier families with working parents.

As Austin said to Today/Reuters, “In terms of need, it is backwards.”16

Projecting impacts of raising the minimum wage

Skyrocketing the minimum wage to $15 per hour would have deep impacts. That would be an increase of 107 percent.

That’s over double the current minimum wage and would capture far, far more workers than a modest increase. How many? Roughly one-third nationally, and over 40 percent in North Carolina.17

In 2015 the University of New Hampshire Survey Center surveyed U.S. economists for the Employment Policies Institute. The survey found large majorities of economists opposed a $15 per hour minimum wage and believed it would result in:

- Fewer jobs available

- Lower youth employment levels

- Lower adult employment levels

- Employers having to require greater skills for entry-level positions

- Small businesses having a harder time staying in business18

Raising the minimum wage would increase unemployment among young and unskilled workers. Why? Because employers would be more likely to expect their output to be less than the cost to hire them. That cost includes not only wages, but also unemployment insurance taxes, payroll taxes, and Obamacare penalties.

So if the minimum wage were set at $15 per hour, it would force the cost to employ anyone at that wage to be at least $18.61 per hour.19 Employers facing such a steep hiring cost would have to be extra selective out of business necessity. Automation (machinery, kiosks, etc.) would likewise become more price-competitive options for businesses.

How far-reaching the job losses would be with a spike in the minimum wage to $15 per hour is an open question. No increase of the magnitude under discussion has ever been seen before. As huge as that is, it’s not something that would have been anticipated in economic research literature.

The $10.10 per hour minimum wage idea of 2013 was the subject of a study published in the December 2014 issue of the Journal of Labor Research. Economists Andrew Hanson of Marquette University and Zackary Hawley of Texas Christian estimated that increase, which as a 38 percent hike is several levels smaller than a 107 percent hike, would eliminate as many as 1.5 million jobs nationwide.20

Very recently, some economists have attempted to address the question of disemployment effects of a $15 per hour minimum wage.

In July 2015, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, former Congressional Budget Office director and former chief economist of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, and economist Ben Gitis produced estimates for the $12 per hour and $15 per hour minimum wage proposals. Forcing the minimum wage to $12 per hour would cost the nation 3.8 million jobs, they estimated. A minimum wage of $15 per hour would destroy 6.6 million jobs.21

In July 2016, economist James Sherk estimated that raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour would affect about one-third of workers nationally. It would reduce their employment by about 19 percent, which would mean 6.9 million fewer jobs.22

Projected impacts for North Carolina

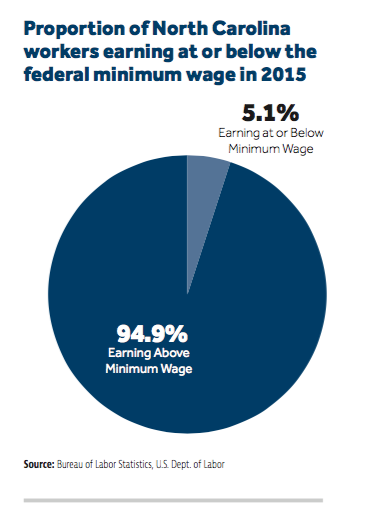

The minimum wage in North Carolina is tied to the federal minimum wage.23 According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, only 5.1 percent of hourly paid wage and salary workers in North Carolina were paid at or below the current minimum wage of $7.25 per hour in 2015.24

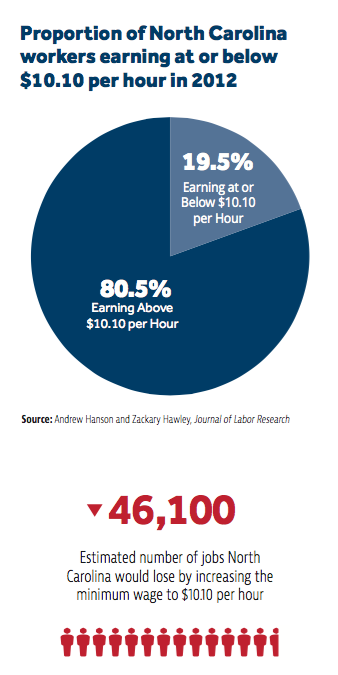

An increase of the minimum wage to the $10.10 per hour level proposed in 2013 would impact a much larger proportion of workers: 19.5 percent in 2012. Workers earning above the current minimum wage but below $10.10 per hour would be included.

Hanson and Hawley estimated that raising the minimum wage to $10.10 per hour would cost North Carolina over 46,000 jobs.25

According to the most recent estimates published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly wage in North Carolina was $15.91 in May 201526 — only 91 cents higher than the $15 per hour wage proposed to be made the minimum hourly wage.

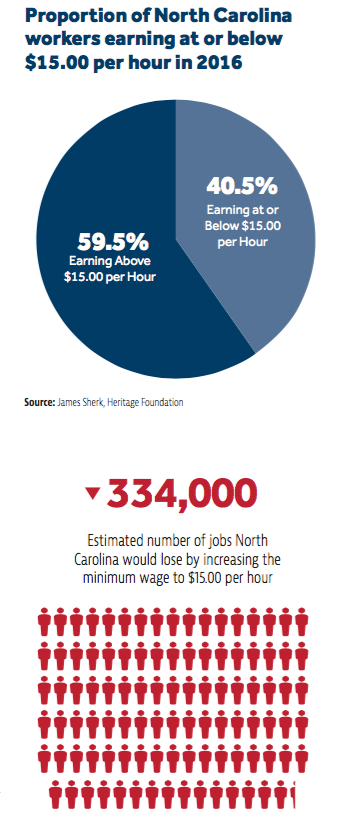

That alone implies heavy disemployment effects in North Carolina from forcing the minimum wage to $15 per hour. Such a wage would impact over 40 percent of North Carolina workers.

Sherk estimated that raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour would cost North Carolina 334,000 jobs (full-time equivalent).27

Conclusion and recommendations

Economic research consensus is clear on the negative effects of a higher minimum wage on low-skilled, poor, and teenage workers. Advocates who believe they will be helping them are confusing their good intentions with good outcomes.

A higher minimum wage can’t increase the skill level of any worker. It can’t expand payrolls. It can’t keep the hours offered by employers steady. It can’t make automation less price-competitive to more expensive human labor.

Finally, it can’t make employers stay in business.

All it can do is make it more expensive to employ low-level workers.

For teenagers (especially poor teens) and the least skilled, inexperienced, and poorest workers — the ones we’d like to see have more opportunities to become productive workers in North Carolina — they’re the ones most likely to be left behind by a minimum wage increase.

State policymakers have been wise to resist the pressure to raise the state minimum wage. There is no good reason to inflict any greater harm to the poorest, least skilled, and least experienced workers in North Carolina than the federal minimum wage already does.

For all these reasons, North Carolina’s policymakers should therefore continue to keep the state minimum wage no higher than the federal minimum wage.

They should also urge their federal counterparts against increasing the minimum wage, especially to the unprecedented cliffs of $15 per hour.

Endnotes

[1] Dave Jamieson, “Obama Gets Behind Democrats’ $10.10 Minimum Wage Proposal,” The Huffington Post, November 7, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/07/obama-minimum-wage_n_4235965.html.

[2]Tim Devaney, “Dems line up behind $12 minimum wage,” The Hill, April 20, 2015, http://thehill.com/regulation/labor/240702-obama-administration-backing-12-minimum-wage.

[3] Colin Campbell, “NC Senate Democrats want to raise minimum wage to $12 an hour,” The News & Observer, May 25, 2016, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/politics-columns-blogs/under-the-dome/article79886562.html.

[4] See, e.g., Hermant Mehta, “At the DNC, a North Carolina Preacher Delivered a Sermon Even Atheists Could Get Behind,” Patheos, July 28, 2016, http://www.patheos.com/blogs/friendlyatheist/2016/07/28/at-the-dnc-a-north-carolina-preacher-delivered-a-sermon-even-atheists-could-get-behind; cf. Martha Waggoner, “‘Moral Day of Action’ rallies focus on workers, poor, sick,” The News & Observer, September 12, 2016, http://www.newsobserver.com/news/nation-world/national/article101314092.html and Lauren McCauley, “Nationwide, Workers Join Clergy to Demand Lawmakers Advance Politics of Morality,” Common Dreams, September 12, 2016, http://www.commondreams.org/news/2016/09/12/nationwide-workers-join-clergy-demand-lawmakers-advance-politics-morality.

[5] “Raise the minimum wage, lift the economy,” editorial board opinion, The News & Observer, April 5, 2016, http://www.newsobserver.com/opinion/editorials/article70141592.html.

[6] Session Law 2016-3, http://www.ncga.state.nc.us/gascripts/BillLookUp/BillLookUp.pl?Session=2015E2&BillID=hb+2&submitButton=Go.

[7] See the North Carolina Constitution, Article VII, Section 1, http://www.ncga.state.nc.us/legislation/constitution/ncconstitution.html.

[8] David Neumark and William Wascher, “Minimum Wages and Employment: A Review of Evidence from the New Minimum Wage Research,” NBER Working Paper No. 12663, National Bureau of Economic Research, November 2006, http://www.nber.org/papers/w12663.

[9] David Neumark, J.M. Ian Salas, and William Wascher, “Revisiting the Minimum Wage-Employment Debate: Throwing Out the Baby with the Bathwater?” NBER Working Paper No. 18681, National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2013, revised May 2013, http://www.nber.org/papers/w18681.

[10] David Neumark, J.M. Ian Salas, and William Wascher, “More on Recent Evidence on the Effects of Minimum Wages in the United States,” NBER Working Paper No. 20619, National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2014, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20619.

[11] News release, “Federal minimum wage will increase to $7.25 on July 24,” United States Department of Labor, July 26, 2009, https://www.dol.gov/opa/media/press/esa/esa20090821.htm.

[12] Jeffrey Clemens and Michael Wither, “The Minimum Wage and the Great Recession: Evidence of Effects on the Employment and Income Trajectories of Low-Skilled Workers,” NBER Working Paper No. 20724, National Bureau of Economic Research, December 2014, http://www.nber.org/papers/w20724.

[13] Algernon Austin, “Poorest teens have hardest time finding summer jobs, Economic Snapshot, Economic Policy Institute, May 11, 2011, http://www.epi.org/publication/poorest_teens_have_hardest_time_finding_summer_jobs.

[14] William E. Even and David A. Macpherson, “The Teen Employment Crisis: The Effects of the 2007 – 2009 Federal Minimum Wage Increases on Teen Employment,” Employment Policies Institute, July 2010, http://www.epionline.org/studies/r128.

[15] Allison Linn, “A teen with a job becomes a rarity in US economy,” Today Money, May 3, 2012, http://www.today.com/money/teen-job-becomes-rarity-us-economy-750378.

[16] Linn, “A teen with a job becomes a rarity.”

[17] James Sherk, “How $15-per-Hour Minimum Starting Wages Would Affect Each State,” Issue Brief No. 4601, Heritage Foundation, August 17, 2016, http://report.heritage.org/ib4601.

[18] Tracy A. Fowler, Ph.D. and Andrew E. Smith, Ph.D., preparers, “Survey of US Economists on a $15 Federal Minimum Wage,” The Survey Center University of New Hampshire for the Employment Policies Institute, November 2015, https://www.epionline.org/studies/survey-of-us-economists-on-a-15-federal-minimum-wage.

[19] James Sherk, “Raising Minimum Starting Wages to $15 per Hour Would Eliminate Seven Million Jobs,” Issue Brief No. 4596, Heritage Foundation, July 26, 2016, http://www.heritage.org/research/reports/2016/07/raising-minimum-starting-wages-to-15-per-hour-would-eliminate-seven-million-jobs.

[20] Andrew Hanson and Zackary Hawley, “The $10.10 Minimum Wage Proposal: An Evaluation Across States,” Journal of Labor Research, Volume 35, Issue 4, December 2014, pp. 323–345, http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12122-014-9190-8.

[21] Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Ben Gitis, “Counterproductive: The Employment and Income Effects of Raising America’s Minimum Wage to $12 and to $15 per Hour,” Issue Brief No. 36, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research and American Action Forum, July 2015, https://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/counterproductive-employment-and-income-effects-raising-americas-minimum-6356.html.

[22] Sherk, “Raising Minimum Starting Wages to $15 per Hour Would Eliminate Seven Million Jobs.”

[23] North Carolina General Statutes §95-25.3(a): “Every employer shall pay to each employee who in any workweek performs any work, wages of at least six dollars and fifteen cents ($6.15) per hour or the minimum wage set forth in paragraph 1 of section 6(a) of the Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. 206(a)(1), as that wage may change from time to time, whichever is higher, except as otherwise provided in this section.”

[24] “Minimum Wage Workers in North Carolina—2015,” News Release 16-1155-ATL, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 9, 2016, http://www.bls.gov/regions/southeast/news-release/minimumwageworkers_northcarolina.htm.

[25] Hanson and Hawley, “The $10.10 Minimum Wage Proposal: An Evaluation Across States.”

[26] “May 2015 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates—North Carolina,” Occupational Employment Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nc.htm, accessed on September 16, 2016.

[27] Sherk, “How $15-per-Hour Minimum Starting Wages Would Affect Each State.”