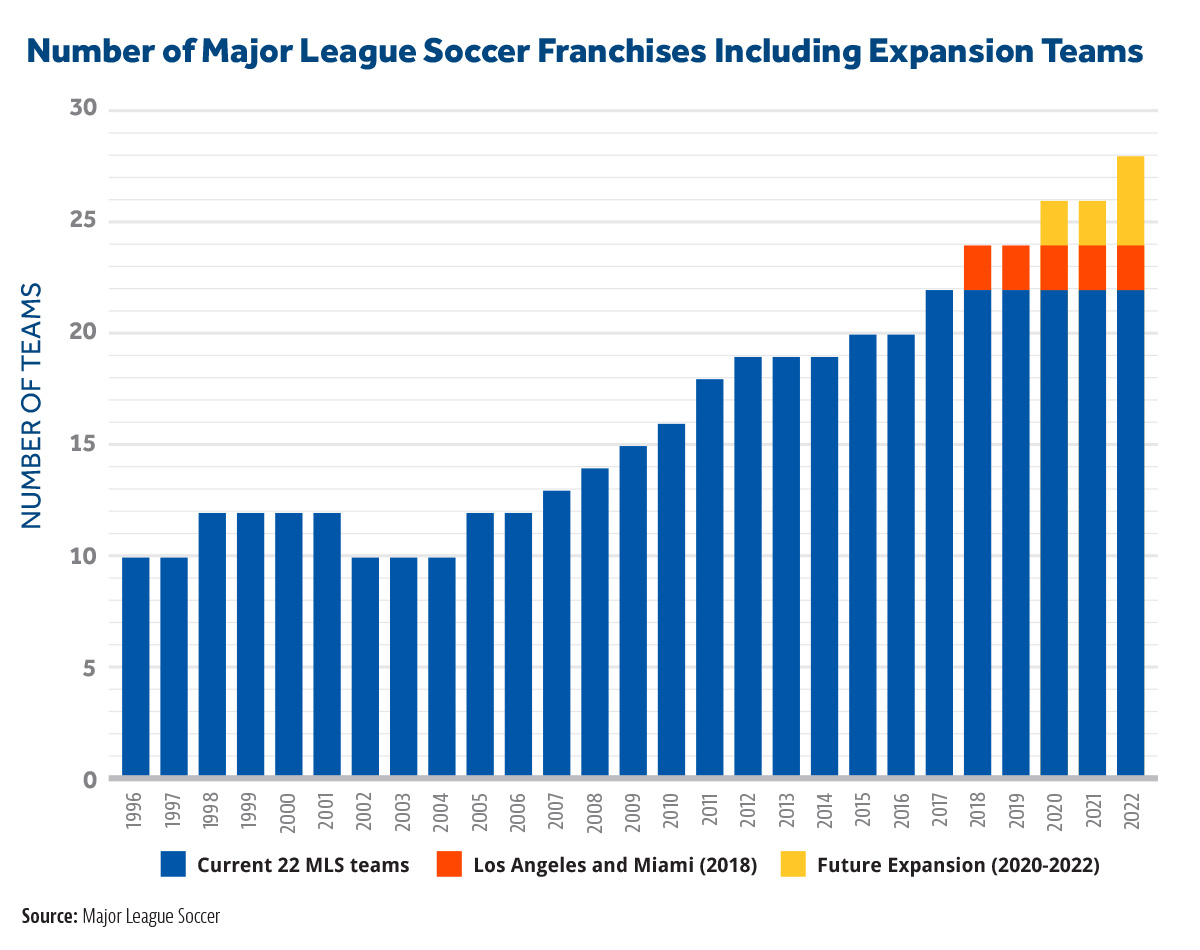

When Major League Soccer (MLS) started play in 1996, there were 10 teams in the league and the whole undertaking faced an uncertain future. Despite the wild popularity of soccer internationally, no one was quite sure whether it would really take off in the United States, and whether it would be able to compete with its well-established, often homegrown counterparts in other sports – NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL.

Twenty-one years later, MLS seems to be thriving. The league has seen steady growth and now boasts 22 teams, with six more expansion teams planned by 2022. MLS has already determined that it will add teams in Los Angeles and Miami. To fill the other four slots, MLS officials solicited bids that were due to the league by late January 2017. From this group of applicants, the league plans to add two more teams in 2020 and another two in 2022, bringing the total to 28. At the time of publication, the cities for the 2020 and 2022 expansions have not been announced.

North Carolina bids

Ownership groups in 12 cities submitted bids to MLS for the two franchises that would begin play in 2020. Two of those were in North Carolina – Charlotte and Raleigh. The others were Cincinnati, Detroit, Indianapolis, Nashville, Phoenix, Sacramento, San Antonio, San Diego, St. Louis, and Tampa/St. Petersburg. Major League Soccer requires any city wishing to attract an expansion franchise to have a viable business plan, commitments for stadium naming rights and jersey sponsors, and plans for training facilities and soccer academies. Moreover, the next two teams will be required to pay a $150 million franchise fee.1

The most notable requirement, from a public policy standpoint, is that each team needs to submit plans for a stadium. MLS essentially requires a soccer-specific stadium for any new team, with seating for about 20,000 located closer to the field than a traditional football stadium. And this has turned out to be the big sticking point for MLS bids. Soccer stadiums are expensive, with many proposals in the $150 to $200 million range. The question, then, has been how to fund the building of these stadiums. Cities and ownership groups have answered that question in radically different ways, and North Carolina offers two examples that are themselves quite different from each other.

Charlotte

In Charlotte, the group is led by Marcus Smith, who is president, chief executive officer, and director of Speedway Motorsports, Inc. Smith is proposing a new stadium at the site of Memorial Stadium and the Grady Cole Center in the Elizabeth community of Charlotte. The stadium would cost an estimated $175 million, and Smith has asked that local governments assume some of that expense. He originally asked the city and the county to put up $43.75 million each, with a plan to finance the other $87.5 million himself. Of Smith’s share, $12.5 million would be paid up front. The other $75 million would come in the form of a loan from the county, which Smith would repay over 25 years. Smith would control revenue and manage the facility calendar, but the county would retain ownership of the stadium itself, including the responsibility to fund required maintenance. Mecklenburg County commissioners initially voted to support the plan, but the Charlotte City Council refused to consider it. Then, in June, the city said that it might consider putting in as much as $30 million, but didn’t commit to anything. And on August 2, Mecklenburg County commissioners rescinded their offer to Smith, instead saying they’d be willing to donate the land to the city for the project, but nothing else.2 Smith has not withdrawn his bid, but stadium financing seems to be becoming an ever more difficult issue.

Raleigh

Meanwhile, in Raleigh, Steve Malik, owner of existing professional soccer team North Carolina FC, has also put in a bid. In July, he announced a preferred site in downtown Raleigh, and a plan to spend an estimated $150 million for the facility. Malik is planning to finance the stadium using his own funds and funds from an investor group he is assembling. However, the site he’s announced sits on state-owned land, and the NCFC ownership group has expressed a desire to lease the land from the state while retaining ownership of the stadium.3 State officials have suggested the land may be worth around $91 million4, assets the state would no longer be able to sell or use for other purposes, so any such arrangement would constitute significant taxpayer investment in the stadium project.

Publicly financed stadiums: don’t believe the hype

It is not unusual for cities, counties, and even states to kick in significant amounts of taxpayer money to build a stadium for a professional sports team. For decades, it has been common for teams and owner groups to ask governments for large sums of money to build the stadiums in which they will play. Buoyed by dubious studies about the economic impact teams will have in their cities, they ask for local governments to spend tens or even hundreds of millions building state-of-the-art facilities. Taxpayers end up footing the bill through increased property and other taxes.

Officials, of course, claim that all of this is good for the economy and therefore the residents of the region. The spectators flooding into the city for sporting events would spend money in restaurants and hotels, both of which are taxed heavily. Conceptually, these expenditures would increase revenue, grow businesses, and create employment. In addition to the soccer (or baseball or football or basketball or hockey) games played in the stadium, it would serve as an attractive venue for concerts and other events, which would similarly spur economic growth. And on top of that, having this sort of venue and the sports and concerts it brings would make the city more attractive to top talent. Supposedly, big companies would be more likely to move to the city, knowing they can hire smart young people to fill jobs. The fantastical tax revenue cascade depicted by boosters of such plans compels taxpayers and elected officials to believe that building a stadium will “more than pay for itself.”

The real effects on the local economy are indisputable

But there is substantial evidence to the contrary. Many researchers have studied whether spending large amounts of public money on a stadium for a professional sports franchise produces the sorts of economic benefits that advocates claim.5 In September 2015, Dennis Coates, Professor of Economics at University of Maryland, Baltimore County, published one such study, a working paper titled “Growth Effects of Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Arenas: 15 Years Later.” It was a follow-up to a 1999 study in which the authors had examined every city with an NBA, NFL, or MLB franchise between 1969 and 2004. In this new study, Coates added cities with NHL and MLS franchises and extends the study to 2011.

His findings are striking. The presence of a professional sports team does indeed impact the economy, but, contrary to popular belief, the impact is usually negative. Remarkably, when looking across all sports over the past 50 years, it appears that cities with professional teams saw their per-capita gross domestic product drop. In other words, people became poorer. He writes:

…the entire sports environment matters for the level of real personal income per capita, in the sense that the array of sports variables are jointly statistically significant. But contrary to the promised increase, the presence of a major sports franchise lowers the income.6

Studies that reach these conclusions aren’t new. In 1999, economist Raymond Keating published an analysis called “Sports Pork: The Costly Relationship between Major League Sports and Government” for the Cato Institute. In it, looking back over the 20th century, he calculated that nearly $15 billion in government subsidies had been spent on arenas for the MLB, NFL, NBA, and NHL. (MLS was too new to be included.) He concluded:

The economic facts, however, do not support the position that professional sports teams should receive taxpayer subsidies. The lone beneficiaries of sports subsidies are team owners and players. The existence of what economists call the “substitution effect” (in terms of the stadium game, leisure dollars will be spent one way or another whether a stadium exists or not), the dubiousness of the Keynesian multiplier, the offsetting impact of a negative multiplier, the inefficiency of government, and the negatives of higher taxes all argue against government sports subsidies. Indeed, the results of studies on changes in the economy resulting from the presence of stadiums, arenas, and sports teams show no positive economic impact from professional sports or a possible negative effect.7

The reason is the “substitution effect,” a well-known concept in the economics and business literature. People have a limited number of hours and dollars, and some percentage of those are spent on leisure activities. A new Major League Soccer team in Raleigh or Charlotte will certainly attract fans who will spend money. But the overwhelming majority of those will be fans who live locally, and they will not be spending new money. Instead, they’ll substitute. Local fans will spend money at an MLS match instead of going to see the Hornets in Charlotte or the Hurricanes in Raleigh, or minor league baseball in either area. Or they will spend money on MLS that they would have spent going bowling, to the movies, or to a concert. The overall amount of money spent in the economy isn’t different; it’s just redistributed.

Unfortunately, the unintended consequence can even be to take business away from small, local competitors, which is usually the last thing any politician or resident wants for the local economy. A new stadium doesn’t magically increase the entertainment budgets of local residents. In fact, it may do just the opposite if that stadium is paid for through increased taxes.

The added expense of keeping teams

There is also another irony in all of this. Usually, under publicly funded stadium plans across the country, the city or county retains ownership of the stadium, while the team and its owners control revenue. This would be the case under Smith’s plan in Charlotte, where the county would own the site. In Raleigh, the proposal seems to be that the state would own the land while the team would own the stadium, but the details on this point are still unclear. At first glance, this may seem like a good deal for taxpayers because the county would hold on to an asset. Indeed, the NCFC owners made just this point in a memo to state leaders.8 In Raleigh, the owners do suggest that they would pay taxes on the property; in Charlotte, the stadium would be exempt from property taxes because both the land and the stadium itself would be owned by a local government.

But if we view it from the owner’s perspective, the picture changes considerably. If the city or county owns the stadium, or even just the land upon which it sits, then the team’s ownership group loses little by moving the team. If another city comes to them with the offer of a shiny new stadium 15 or 20 years from now, they have every reason to seriously consider accepting the offer and leaving town. Unless, that is, elected officials make counteroffers to encourage them to stay, deals that would likely include more favorable terms, more tax breaks, or stadium improvements, all of which would cost the taxpayers money.

Contrast that to a completely privately financed bid where the team owns the stadium. In that case, leaving involves finding a buyer or a tenant, and ensuring the sale or lease is lucrative enough to justify the move. It’s easier just to stay put, in the same way that people who rent their homes can move more frequently and easily than people who own their homes. Ironically, putting up large amounts of public money to build a stadium may make it harder to hold on to the team that occupies that stadium over the long term.

Conclusion

Sports, particularly major league sports, is big business. In the most recent valuations published by Forbes last year, the average MLS team was worth more than $185 million, with the most valuable at $285 million. That was an 18 percent increase in average value just from the previous year, part of a trend of extreme growth over the last two decades. The primary beneficiaries of that growth will, of course, be the owners of those teams.

It is therefore right that those same owners should build the facilities necessary for their businesses to thrive, in the same way that we expect all sorts of other private businesses to build or privately rent office and retail spaces. Fortunately, there seems to be a move in this direction, at least for MLS. Of the 12 bids received this year, five included plans for privately financed stadiums. The fact that nearly half of the owner groups were confident they could build stadiums and develop successful business plans that didn’t rely on taxpayer funding should act as encouragement to cities and counties across North Carolina and the rest of the country. Large subsidies aren’t necessary to attract major league sports, and stadiums don’t have to be built using taxpayers’ scarce dollars. The city and its taxpayers will be better served by leaving the building of stadiums to the private businesses that will benefit most from them.

Endnotes

1. “MLS announces expansion process and timeline,” mlssoccer.com/post/2016/12/15/mls-announces-expansion-process-and-timeline

2. http://www.charlotteobserver.com/news/politics-government/article165118902.html

3. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3900189-MLS-proposal.html

4. http://www.wral.com/sale-price-of-state-land-sought-by-soccer-club-tops-91m/16851946/

5. Coates, Dennis and Brad R. Humphreys, “Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Subsidies for Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Mega-Events?” Working Paper Series, Paper No. 08-18, International Association of Sports Economists and North American Association of Sports Economists, August 2008. college.holycross.edu/RePEc/spe/CoatesHumphreys_LitReview.pdf

Lertwachara, Kaveephong and James J. Chochran, “An Event Study of the Economic Impact of Professional Sport Franchises on Local U.S. Economies,” Journal of Sports Economics, June 1, 2007.

Matheson, Victor, Robert Baade, and Mimi Nikolova, “A Tale of Two Stadiums: Comparing the Economic Impact of Chicago’s Wrigley Field and U.S. Cellular Field” (2006). Economics Department Working Papers. Paper 70. http://crossworks.holycross.edu/econ_working_papers/70

Noll, Roger G. and Andrew Zimbalist, “Sports, Jobs, & Taxes: Are New Stadiums Worth the Cost?” The Brookings Institution, June 1, 1997. brookings.edu/articles/sports-jobs-taxes-are-new-stadiums-worth-the-cost/

Propheter, Geoffrey, “Are Basketball Arenas Catalysts of Economic Development?” Journal of Urban Affairs, February 17, 2012. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2011.00597.x/abstract

Rappaport, Jordan and Chad Wilkerson, “What Are the Benefits of Hosting a Major League Sports Franchise?” Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, First Quarter 2001. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8386/2fca56f4248acffce35d69896c6ad66d6c22.pdf

“Roger Noll on the Economics of Sports,” EconTalk Episode, August 27, 2012. econtalk.org/archives/2012/08/roger_noll_on_t.html

Wilhelm, Sarah, “Public Funding of Sports Stadiums,” Policy Brief: 04-30-08, Center for Public Policy & Administration, The University of Utah, gardner.utah.edu/_documents/publications/finance-tax/sports-stadiums.pdf

6. Coates, Dennis, “Growth Effects of Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Arenas: 15 Years Later.” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, September 2015, p. 4. mercatus.org/system/files/Coates-Sports-Franchises.pdf, p4

7. Keating, Raymond J. “Sports Pork: The Costly Relationship between Major League Sports and Government,” Policy Analysis, Cato Institute, p. 1. object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa339.pdf

8. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/3900189-MLS-proposal.html