Few, if any, observers expected that a weekend trip to Iceland in October 1986 could play a pivotal role in ending the Cold War. But the two days of arms control negotiations in Reykjavik featuring American President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, planned as a prelude to a larger summit in Washington the following year, ended up playing a much larger historical role than any of the participants imagined.

Few, if any, observers expected that a weekend trip to Iceland in October 1986 could play a pivotal role in ending the Cold War. But the two days of arms control negotiations in Reykjavik featuring American President Ronald Reagan and Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, planned as a prelude to a larger summit in Washington the following year, ended up playing a much larger historical role than any of the participants imagined.

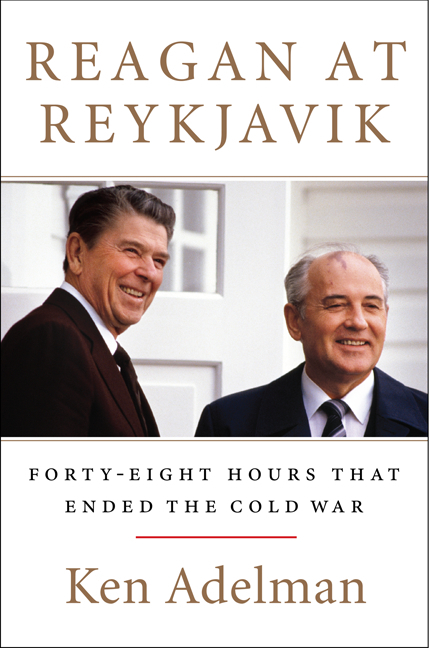

Reagan arms control director Ken Adelman recounts the details of the meeting that evolved into a summit in the new book Reagan at Reykjavik: Forty-eight Hours That Ended the Cold War. Adelman was there, and he offers plenty of first-hand details about the event and its aftermath. But the book also benefits from a reliance on recently declassified transcripts of one-on-one meetings between the two principals (and two-on-two meetings adding the U.S. secretary of state and Soviet foreign minister) . Of particular interest to the author is the back-and-forth debate among two world leaders untethered to their advisers and prepared scripts.

This Sunday morning session furnishes insights like none other at Reykjavik, and like few other summits in modern history. These hours revealed Reagan and Gorbachev always on their own and sometimes at their best.

Their discussion was of impressive depth and breadth, ranging from how Soviet intermediate missile deployments in Asia affected European security, to the vast tapestry of comparative politics — of totalitarian Communism versus democratic capitalism. …

… Reagan and Gorbachev handled these topics themselves. Neither turned to his foreign minister for either information or guidance during their three and a half hours of steady substance. During their dialogue that morning, Reagan and Gorbachev were most intensively active and alive. Each must have been feeling that “this is the real me.”

The session also revealed how, and how much, the men differed. Gorbachev acted like a capitalistic CEO trying to analyze and solve the issues at hand. Reagan resembled a Russian artist, flitting here and there, following his imagination about.

Moreover, the president showed a wider range of interests than Gorbachev. He was willing, even eager to debate the great issue of their era, Marxism versus democracy, while Gorbachev kept yanking him back to the tasks at hand.

Sunday morning likewise revealed that even Communism’s supreme leader could not justify its ways. By the end of 1986 the clock was already running down on Communist ideology and legitimacy. Gorbachev tried to respond to Reagan’s attack on his system but did a poor job of it. His discourses on jamming VOA, Americans being unable to watch Soviet films, and the existence of multiple political parties under Communism were his weakest at Reykjavik. They may even have embarrassed him.

Gorbachev had no good response to Reagan’s critique. A man that intelligent and clear-sighted had to have seen that. He had to have known that Reagan was basically right and that the path the Soviet Union had taken was basically wrong.

For sure, Reagan had the better case to make, but he made it boldly, pulling no punches. It’s hard to think of any other U.S. president speaking as bluntly against the Soviet system to the head of that system as Reagan did that morning.

Other interesting insights focus on the sleepless, adrenaline-fueled schedules of summit support staff, and the news media’s propensity for turning its own ill-informed analysis into news. This is an excellent addition to the library of Reagan–related reading.