Short term “payday” lending is in the news again, it seems. The Obama administration’s Justice Department is beginning a new campaign against the lenders. Search engine giant Google has just announced it won’t sell ads to the lenders.

The loans certainly are expensive — they’re typically $15 per every $100 borrowed over two weeks (and they’re usually small loans, $500 or less). Critics project that charge beyond the initial two weeks to a full year, yielding what they call an effective annual percentage rate (APR) of 400 percent.

Critics say the loans often cause borrowers to need to take out successive loans till they can finally pay them off. So as they see it, payday lenders make people in need worse off and then profit off them.

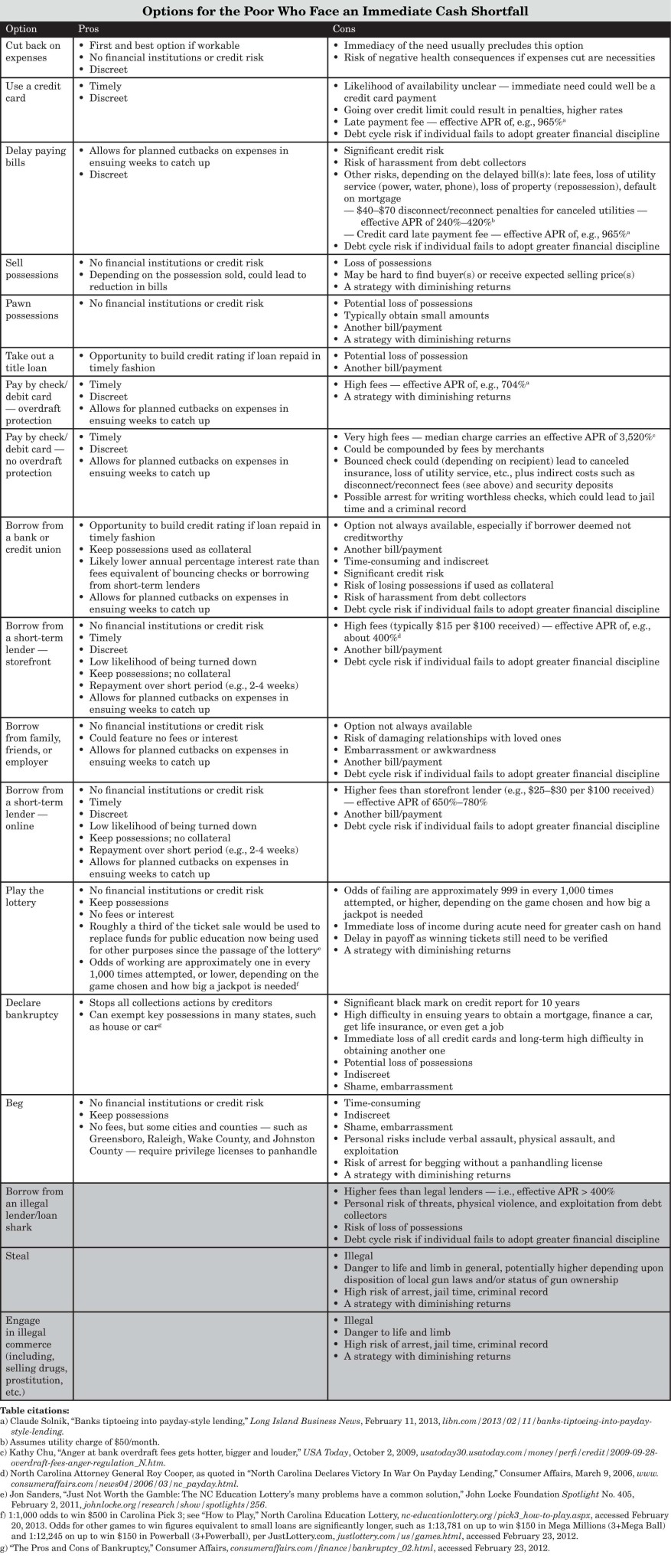

No doubt if you had other options you’d probably choose something else. But what if you don’t? (See below or click the link for a chart of options for poor people facing an immediate cash shortfall.)

I asked in an earlier newsletter on the subject what you would do if you suddenly faced a $300 car repair bill, then asked:

But what if you were an unwed single mother, a high school dropout, trying to make ends meet but barely scraping by from week to week? What if you had made your share of mistakes with credit, and that last thing you wanted to do was spend your time away from work fidgeting nervously in a bank office waiting and waiting to see if you were going to get a check or just another rejection (and worse, a lecture). What if all you wanted was a small amount to cover till you got paid, without the hassle of banks and business hours and having your financial history dissected in front of you? What if you could have that, but it would be costly?

Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York studying the end of payday lending in Georgia and North Carolina found that people in those states “bounced more checks, complained more about lenders and debt collectors, and have filed for Chapter 7 (‘no asset’) bankruptcy at a higher rate” than they would have if the lenders were still legal. The increase in bounced checks especially cost consumers millions of dollars per year.

“Forcing households to replace costly credit with even costlier credit,” they wrote, “is bound to make them worse off.”

Below are some facts from my 2013 report on payday lending, “For Their Own Good: Ban on high-cost lending leaves poor consumers worse off, with fewer choices”:

- About five percent of people use payday lenders, including currently in North Carolina (they go to storefront lenders across state lines or to higher-cost online lenders)

- Payday customers understand the loans’ high cost, though they don’t like it

- Payday customers appreciate several nonmonetary aspects of the loans, including convenient hours and locations, ease, discretion, friendliness, lack of credit risk, and ability to avoid unpleasant personal interactions with friends, families, employers, bankers, and creditors

- About 95 percent of payday loans are repaid

- Nine out of ten people in a tight spot might definitely rule out a payday loan, but the tenth might give it serious consideration; however, since North Carolina has ruled it out for him, the tenth might be stuck with even less desirable options

- Absent payday loans, other options carry fees that equate with high effective APRs: bounced-check fees (3,520 percent without overdraft protection and 704 percent with); utility disconnect or reconnect fees (240–420 percent); credit card late payments (965 percent); and borrowing from an online payday lender (650–780 percent) or loan shark (indeterminate)

As you can see, for those whose choices are between a payday lender and risking a bounced check or late payment, the effective APRs of the latter options are worse than the payday loan’s.

Remember, not everyone comes into a sudden financial need from a pristine starting place. Removing an option nine out of 10 of us would reject because we have better alternatives is still harmful to the tenth person, who doesn’t.