November may be the best time to buy a major kitchen appliance, but counties know it is the worst time to ask voters to raise taxes, especially when there is a presidential election. Since 2007, 76 counties have gone to their voters 159 times to raise the local sales tax by a quarter-cent. That is an average of 2.1 referendum elections per county. Bladen County has already tried six times, each one unsuccessful. County commissioners have won 42 times, but have had much more success when fewer people went to the polls.

Fifty years ago, when North Carolina signed onto Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for the poor, county employees were responsible for administration. Counties paid 15 percent of the non-federal share as a way to ensure that they had a stake in reliably gauging eligibility. Over the next thirty years, however, state and federal rules removed much of the discretion local workers originally had.

In 2007, the state took back the local Medicaid cost and a half-cent of sales tax authority, while promising local governments they would break even at worst. As a final sweetener, the state offered counties the option to raise the local sales tax by a quarter-cent if voters approved. In November of that year, 16 counties put a tax hike on the ballot, and five were approved. Alexander County took no chances and held its tax referendum on January 8, 2008.

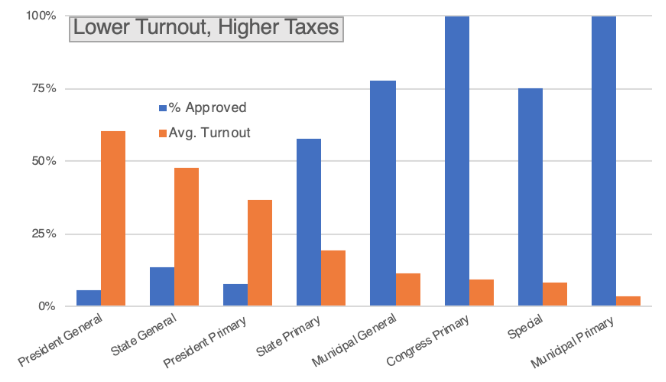

By February 2011, seven other counties had followed Alexander County’s lead and asked voters to take a special trip to the polls for the tax vote. Turnout in those elections was predictably low, with Robeson County setting the pace at 4.2 percent, and approvals of the tax hikes were as predictably likely, as five of the seven referenda passed.

The General Assembly in 2013 removed the ability of counties to hold referenda on the sales tax increase outside of an already scheduled election. Cherokee and Jackson effectively found a loophole in 2016 when they scheduled their sales tax votes in conjunction with the Congressional primary. Voter turnout in Cherokee was 7 percent, and it was 11 percent in Jackson. Needless to say, both passed.

Last year, seven of 12 referenda held in May, with an average turnout of 19 percent, passed. In contrast, just four of 20 held in November, when turnout was 51 percent, passed. It is not surprising, then, that only four of 60 referenda in presidential election years passed, but eight of 10 in municipal elections since the initial round of votes in 2007 did. For municipal elections, that is a higher percentage than the now-outlawed special elections. Looking across 138 elections for which we have voter turnout information, for a 10-point increase in voter turnout, support for the tax increase falls 2.6 points, which means the 32-point difference in voter turnout would imply an 8.3 percent difference in support for the tax.

Three counties have announced plans to try again to win voter approval for a higher sales tax in November or March.

Mecklenburg will try again on November 5th, this time saying the $50 million tax hike will support the arts, education, and parks. Six towns in the northern part of the county would receive earmarked funds, including four who sought the ability to create municipal charter schools in 2018.

Forsyth and Madison have scheduled their second attempts to raise taxes for March 2020. County officials there may be counting on a competitive Democratic primary and a Republican incumbent to yield a different result than we have seen in the past three presidential cycles, which had more competition on the Republican side.

County commissioners have been able to choose their voters over the past decade by scheduling votes when they are more likely to pass. Perhaps state legislators could demonstrate support for taxation only with representation by limiting future tax hike referenda to general elections in even-numbered years.