While the majority of university faculty believe that online teaching is inferior to in-person instruction and invites academic fraud, UNC students now face a fall semester without the advantages of in-class instruction. Given this change, will students pay less? The answer appears to be no.

With the fall 2020 college semester starting soon, the UNC System and its member schools have been scrambling to address the concerns of students, faculty, and their families amid COVID-19. On July 23, the UNC Board of Governors voted to keep the current tuition and fee schedule “regardless of any changes to instructional format that may occur for any part of the [2020-2021] academic year.” Some board members pushed back against the motion, claiming that it was inappropriate to keep charging fees for services that students are prohibited from fully utilizing. In the words of board member Marty Kotis, students will be receiving an “inferior experience” to cover for the system’s financial wounds. Yet, for other board members, the action seemed justified. “We have to support the services associated with the campuses and all the different aspects that continue to support our students,” said board Chairman Randy Ramsey. “The result is the same” added board member Terry Hutchens, referring to the difference in student learning experience between in-person and online classes.

So, where is the revenue from tuition and fees going? For schools such as UNC-Chapel Hill, student tuition and fees yield around $430 million. At the same time, salaries and benefits (the largest expenditure for the school at 56% of operating expenses on average over ten years) are around $1.72 billion. In other words, money from UNC students covers roughly 25% of the employment of their professors, administrators, and other staff. The rest of the salaries and benefits, not to mention the other services that students enjoy, are funded through other means.

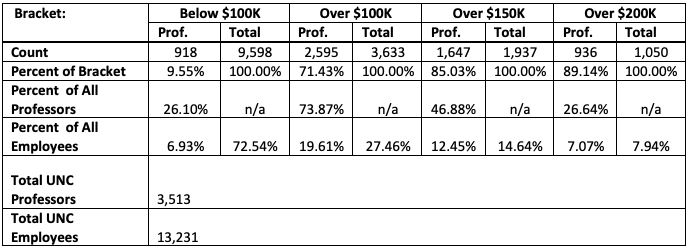

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the median pay for professors is $79,540. If we ignore the industry and look solely at earnings by educational attainment, those with a master’s degree (the minimum academic credential to be hired as a professor) earn a median of $77,844, whereas those with a doctoral degree earn a median of $97,916. Below is a table breaking down the relationship between UNC professors, other employees, and their salaries:

Source: UNC Salary Information Database

By looking at the data, it becomes evident that professors are not as low paid as what is commonly believed. A sizable share of UNC-Chapel Hill professors receive salaries that are more than double the market salary of $79,540. In fact, there are more UNC professors that make over $200K, the highest being $864,910, than those that make less than $100K.

More importantly, the UNC System should use the COVID-19 campus shutdown as an impetus to reevaluate its operations. Reforms such as those outlined by Joe Coletti in the most recent edition of N.C. Policy Solutions are a good place to start. Coletti wrote,

Purdue University in Indiana, a public land grant institution that is similar to NC State University, has taken a different approach. Purdue has reduced administrative costs to keep tuition and fees flat since 2013 and has already set the 2020-21 price, when other schools had not yet determined their tuition and fees for the 2019-20 year. As a result of Purdue’s ability to keep prices low, students’ average annual borrowing fell from $5,451 in the 2010-11 school year to $3,657 in the 2017-18 year.

Purdue’s net tuition has fallen $1,424, or 11 percent since 2013. After being $1,412 above tuition at the highest UNC System school, Purdue is now lower than eight UNC schools, though still $1,017 higher than UNC-Chapel Hill. Surprisingly, Purdue has accomplished this not with higher revenues, which grew at a similar rate as North Carolina’s flagship schools, or through more out-of-state or international enrollment. Instead, Purdue reduced a broad swath of administrative costs by 5 percent between 2012-13 and 2016-17, while it increased instructional spending by 25 percent. Elements of Purdue’s strategic reforms may be worth replicating in North Carolina.

However, the question remains, why must students carry the system’s financial liability? And are the professors and administrative staff working just as hard as they do when teaching face-to-face? Many students go to great lengths to take out loans to pay for their education and the services universities offer, including health services, student-run activities, educational technology, debt services, and campus security being the cores one enjoyed by those physically on campus.

It is counterintuitive for schools not only to continue billing students for certain services while refusing to provide them but also to not refund any fees that were not used for their designated purpose. As such, students are rightfully upset over the fact they must pay for their professor’s lavish salaries, hordes of administrative personnel, and services they’ll never use while struggling to support themselves financially throughout this COVID-19 crisis.