During the last week in March, the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (DPI) conducted a survey to measure the state’s migration to remote learning, that is, the use of video conference, telephone conference, print material, online material, learning management systems, and related means to supplement or supplant traditional classroom instruction. DPI’s Remote Learning Plan Survey captured the responses of 95 traditional school districts and 21 charter and non-traditional schools. The survey results reflected the divergent ways that districts and schools initiated remote learning after Gov. Roy Cooper first directed all public schools to close to students on March 14.

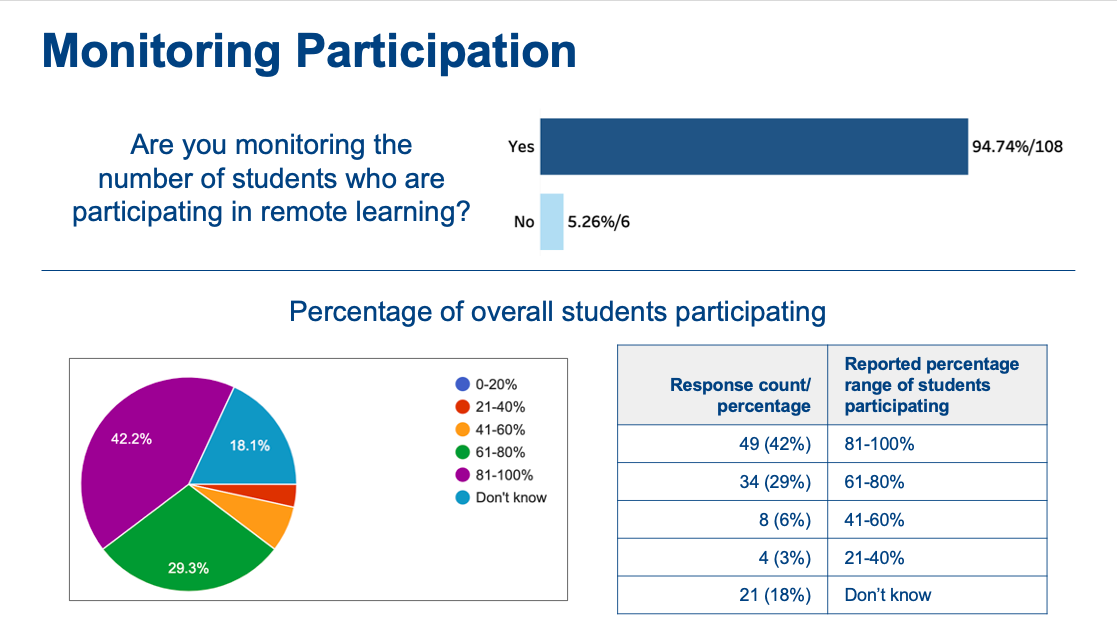

More importantly, the survey revealed startling differences in the number of students participating in remote learning opportunities. For the districts and schools that were actively monitoring student participation, only 42% reported that between 80 and 100% of students participated. Another 40% of respondents had student participation rates below 80%. Alarmingly, the remaining districts and schools did not collect sufficient data to report their remote learning attendance to DPI staff.

Why are teachers struggling to get their students to engage in remote learning?

Source: N.C. Department of Public Instruction

Technology

Some residences, particularly those in rural and low-income communities, do not have access to a reliable internet connection. Mostly private internet providers have made notable gains in boosting broadband availability and quality. Companies including Charter Communications and Comcast even have offered free broadband and wi-fi access to families with children in school. Still, the Inner Banks, Sandhills, and western regions of the state lack the infrastructure needed to support high-quality broadband. Moreover, low-income families are less likely to have a suitable internet-accessible device at home, making it more difficult for disadvantaged populations to access online content during school closure.

The 2020 COVID-19 Recovery Act recently passed by the N.C. General Assembly and signed by Gov. Cooper will begin to bridge the digital divide. The legislation uses federal coronavirus relief dollars to fund $1 million for wi-fi gateway router devices in school buses, $11 million for community and home mobile Internet access points, $4.5 million for a statewide shared cybersecurity infrastructure, and $30 million for computers or other electronic devices for use by students.

Some school districts already have distributed computers and set up internet access points in underserved and low-income communities. According to a recent article published in the Winston-Salem Journal, within a few days of Gov. Cooper’s March 14 school closure announcement, the Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools “loaned about 23,000 devices to students and delivered about 3,300 internet hotspots to students lacking wi-fi.” Despite these efforts, school administrators reported that around 9% of students in the district have not logged on to their teacher’s remote learning site. School districts that have fewer resources likely have much higher nonparticipation rates.

Grades

“The week before they released the grading policy, I had 85% of my students working,” a public school teacher recently wrote on Facebook. “Now I have 30%.” The “grading policy” refers to guidance issued by the N.C. State Board of Education on April 23, which was designed “to ensure no students receive a failing grade and that students’ grades as of March 13 serve as a minimum or a hold harmless point.”

According to the approved policy, students in grades K-5 will not receive a final grade. Middle school students will receive a final grade of “pass” or “withdraw,” depending on their mastery of course standards. In lieu of a grade, teachers are expected to provide academic and social/emotional feedback to families of both elementary and middle school students. Students in grades 9 through 11 have the choice of receiving a grade or the pass/withdraw option that will not impact their grade point average. If families choose the graded option, the final grade will be based on work completed as of March 13 or during the subsequent period of remote learning if the grade improved during that time. High school seniors will receive “a Pass “PC19” or Withdrawal “WC19″ based on their learning as of March 13 for all spring courses in progress on that date.”

Teachers, including the one quoted above, are now confronting the unintended consequences of this policy. Of course, grades are not the only incentive in play. Parents continue to hold their children accountable for completing their work. A small number of students possess an intrinsic desire to work hard or satisfy the expectations of their teachers, parents, or themselves. For many students, however, grades (specifically the possibility of a failing grade) are the principal reason why they invest time and effort in their assigned schoolwork.

Household Factors

Ann Doss Helms of WFAE outlined a number of other, perhaps less well known, barriers to remote learning. In addition to the limited availability of wi-fi and internet-accessible devices, Helms points out that school districts have been unable to account for all enrolled students or contact their parents because of changes to childcare, custody arrangements, and work schedules. Families may be in distress due to job loss, mental health issues, illness, or infirmity. And schoolwork often takes a back seat when teenagers forced to become caretakers or breadwinners.

What about learning?

Remote learning participation rates only tell half the story. Teachers complain that the quantity and quality of the work completed by students have not been satisfactory. The relationship between participation and learning remains to be seen. At this point, we have no idea how much or how little learning is taking place. But it is safe to assume that many challenges await educators when the 2020-21 school year begins in August.

Note: Comcast does not operate in North Carolina. It was included in the article as a general example of companies offering free internet to students during coronavirus-related school closures.