It’s a tale of two state budget pictures. A new report from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University compares North Carolina’s fiscal solvency to those of other states. Meanwhile, the General Assembly’s fiscal staff projects this state’s future spending and revenue numbers. The competing conclusions could leave your head spinning.

Mercatus has conducted its survey of fiscal conditions in the states for four years. It’s based on each state’s comprehensive annual financial report or CAFR. The CAFR provides a full picture of money flows into and out of government coffers. North Carolina has jumped six places in the Mercatus rankings each of the last two years, climbing from No. 27 in 2015 to No. 15 in the latest report. Legislators have achieved these improvements with slower spending growth, higher savings, and lower taxes. The state’s ranking should continue to improve as additional reforms take effect.

Such good news about what has happened has been overshadowed by a forecast of what could happen. Democrats in the State Senate asked the General Assembly’s Fiscal Research Division (North Carolina’s version of the Congressional Budget Office) to forecast revenues and expenses over the next five years based on policies enacted in the recently passed budget.

Fiscal researchers project budget gaps beginning in 2018-19 that reach $1 billion annually by 2020-21. This assumes the economy, population, and prices grow at roughly the same rate as they have in recent years. It also assumes that every policy remains as written and that it continues to work the same way. The only difference: Those policies will cover more people at a higher cost. The projection also assumes that state government is doing exactly the right things, exactly the right way, for exactly the right people, and at exactly the right time. These assumptions might not be accurate.

A more helpful tool would provide ranges for revenues and expenditures in projections. The ranges would show how different levels of productivity, inflation, and economic growth would affect the state budget. There could be a recession. Or there could be a spike in productivity that fuels an economic boom. There’s a range of possibilities. Yet, all uncertainty about the future collapses now into a single estimate of revenue, a single estimate of spending, and a single estimate of the difference each year.

Tax revenues are expected to reach $26 billion in 2021-22, nearly $3 billion more than forecast for the current budget year that started July 1, after a $1 billion annual reduction in taxes and a compound annual growth rate of 2.5 percent. Coincidentally, General Fund appropriations grew at a 2.5 percent compound annual rate between 2010-11 and 2016-17. Without tax reform, increased saving, and other changes, revenue is forecast to grow at a compound annual rate of 3.35 percent.

Spending grows 3.61 percent per year in the projection, which would leave a $200 million gap in 2021-22 without the latest tax reforms. This rate of increase is consistent with the increase in the current budget, which the John Locke Foundation has cautioned could be overly ambitious.

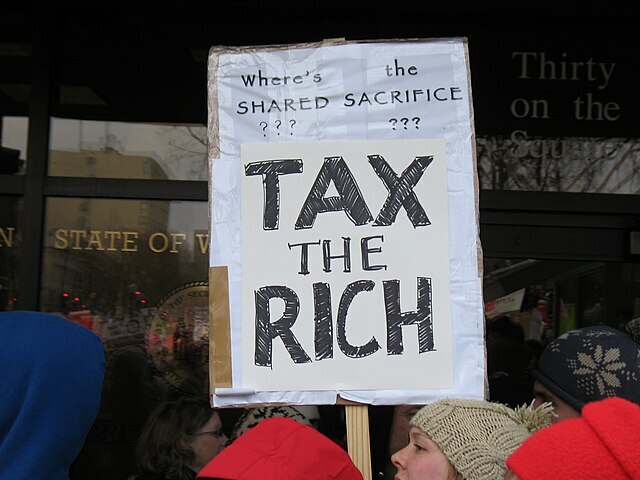

The problem with state government continues to be that politicians have made more promises than they can deliver, and the call to raise taxes has been consistent for decades from those who want more government spending.

Research has been just as consistent in showing that more government revenue depends on faster economic growth, which depends on fewer government-imposed barriers, not higher spending and taxes.