One reason teachers and state employees may not have seen the raises they wanted in recent years is that the government’s cost for pensions and retiree health benefits has climbed from 8 percent of payroll 10 years ago to 19 percent of payroll this year. This difference means $1.1 billion of state General Fund appropriations that could have gone to salaries for active employees instead had to go to those who are retired or to the future retirement benefits of today’s workers.

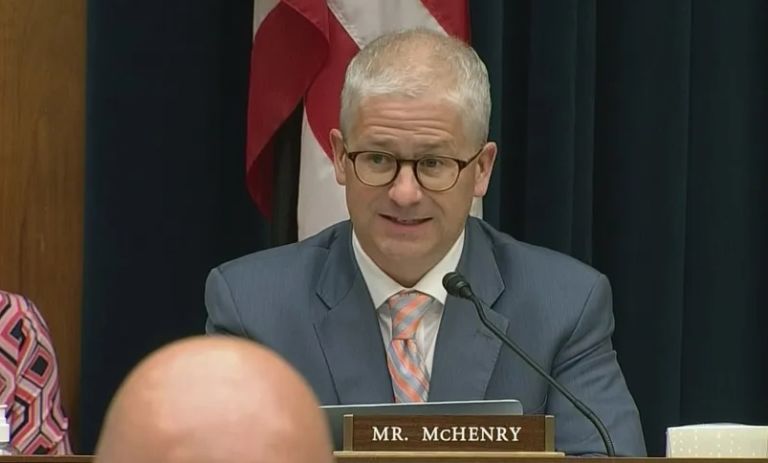

David Vanderweide from the General Assembly’s Fiscal Research Division explained those numbers, their causes, and what lies ahead at the Department of Public Instruction’s Financial and Business Services conference last week.

Vanderweide identified four factors in the climbing contribution rate. First, high interest rates in the 1970s led legislators to increase the discount rate from 4 percent in the early 1960s to 7.5 percent by 1980. The long-term Treasury bond yield fell below the assumed rate of return in the late 1980s and has been below 4 percent for the past decade. Higher discount rates meant the legislature could set aside less for future benefits each year and use that money for current spending.

Increasing life expectancy contributes to the higher cost as well, but the increase has been slow enough that it could be priced into the contributions more easily. More generous benefits have had a larger impact. Between 1963 and 1985 pension benefits became available at younger ages. Whereas nobody could receive a full pension before age 65, employees who start young enough can receive full benefits by age 48. Those benefits became more generous over time as well, from less than 45 percent of pay for someone with 30 years of service in 1963 to 54.6 percent of pay today. Despite this, North Carolina did not expand benefits as much as other states, which has allowed it to avoid making drastic reductions in benefits or encounter the same level of crisis as other states.

Health benefits were never funded with the same foresight as pensions, which has left the state with an unfunded liability of nearly $40 billion in this area. Vanderweide stated that the 6.3 percent of salary state government contributes for retiree health benefits would need to be 16.7 percent to make it actuarially sound. That would raise the total contribution rate for retirement benefits from 18.9 percent to 35.6 percent, adding $1.8 billion to the $2 billion the state currently contributes. If pension contributions had to match the current treasury rate, 81 percent of pay would be needed to fund retiree benefits.

There is hope.

North Carolina government leaders have been far more prudent than the worst states for retirees and taxpayers, such as Illinois and Kentucky. State Treasurer Dale Folwell has taken steps to reduce the cost of managing pension funds and has worked with State Health Plan director Dee Jones to reduce the cost of health care. Last year’s budget bill made new hires after 2020 ineligible for health benefits after retirement, and the retirement system’s board has been taking small steps to ensure more money is set aside each year to pay future pension benefits. In addition to these steps, legislators could reverse some of the decisions made over the past 40 years and reduce pension benefits for future new hires as they did medical benefits. Or they could change the pension system to something more like the IRA and 401k plans that have become the norm for private sector employees over the past half-century.

Without some changes to retiree benefits, a larger share of state employee compensation will be hidden from view. The N.C. Supreme Court has struck down past attempts to spread the cost of restructuring retiree benefits across past and future employees, so if state government is to continue providing the same level of service to residents, it will be future workers who bear most of the burden, creating two classes of state employees. All stakeholders should work together to reduce the size of that burden without impinging on other state spending needs.