Tuesday was #GivingTuesday. Entering its sixth year, the day saw $177 million donated to charities around the world last year. About $70 billion will flow to churches and other nonprofit organizations between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day, a quarter of the total for the year donated by individuals.

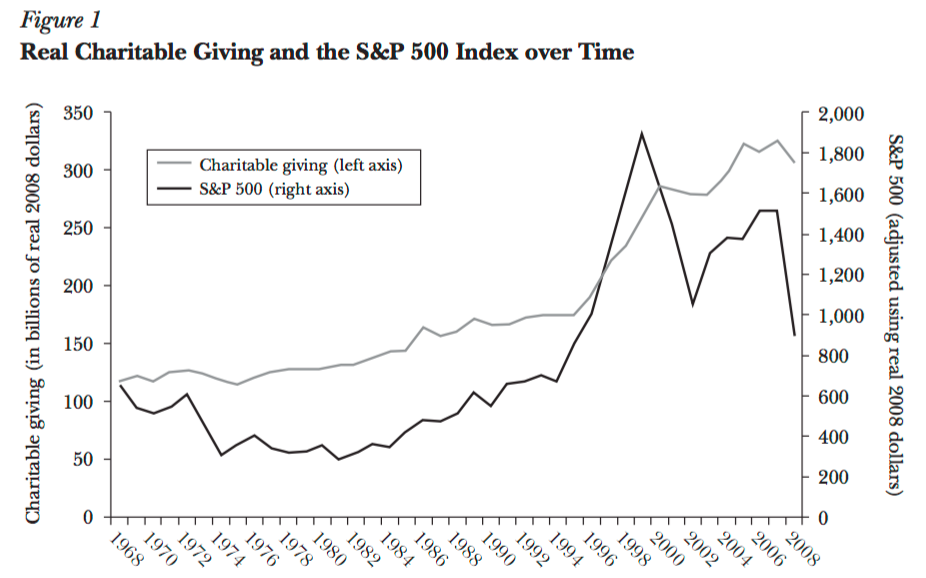

Americans have been generous with their money regardless what tax benefits the federal government bestowed. But every time there is a proposal to cut taxes, someone will see the death of charity at hand. In the 1980s, even as the top tax rate went from 70% to 28%, there was no noticeable change in the increase in donations, as seen in the graph nearby. Giving actually increased 55% faster in the 1980s than in the previous 25 years. Suzanne Garment and Leslie Lenkowsky in an essay on tax reform note the overblown concerns in 1944 about the impact the standard deduction would have on charitable giving.

Americans have been generous with their money regardless what tax benefits the federal government bestowed. But every time there is a proposal to cut taxes, someone will see the death of charity at hand. In the 1980s, even as the top tax rate went from 70% to 28%, there was no noticeable change in the increase in donations, as seen in the graph nearby. Giving actually increased 55% faster in the 1980s than in the previous 25 years. Suzanne Garment and Leslie Lenkowsky in an essay on tax reform note the overblown concerns in 1944 about the impact the standard deduction would have on charitable giving.

This tax reform season is no different. A recent study estimates that an expanded standard deduction could reduce charitable contributions by $13 billion as fewer people itemize donations. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) estimates the charitable deduction to be the third largest tax expenditure after state and local taxes and the mortgage interest deduction, costing the federal government $58.6 billion in fiscal year 2018. In 2010, CRS found that a cap on deductibility could reduce charitable contributions by 1.5%, “but if income effects from the entire budget package are included contributions actually rise 2.5%.” Looking at IRS data on tax returns, a quarter of tax filers take the itemized deduction for charitable giving, but the difference by income is stark: Just 15% of tax filers with adjusted gross income of less than $100,000 took the deduction, compared to 72% of those with incomes over $100,000. It is not surprising that the economist Steve Moore, who has rarely found a tax cut he doesn’t like, has argued that appreciated assets should be taxed before they are given to a charity and charitable gift deductibility should be capped.

David Callahan, co-founder of Demos and founding editor of Inside Philanthropy, in the Guardian last week claimed that ending the death tax and reducing or eliminating the charitable deduction was part of a “withering attack on nonprofits” by Donald Trump and Republicans. “In other countries that have veered into authoritarianism, like Russia,” Callahan writes, “civil society groups have faced outright suppression. Nothing like that has happened in the US yet…”

Callahan himself is not exactly a fan of philanthropists, particularly those on the right. He advocates for “more transparency” by ending donor privacy, restrictions on giving to policy organizations like the John Locke Foundation, and more regulation of donor-advised funds. His concern that Republicans have become hostile to charity should also be put in context. Michael Wear, who “led faith outreach for President Obama’s 2012 election campaign and worked in the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships,” says Democrats have scorned people of faith. He points to President Obama as someone who could bridge the gap, but as a candidate Obama ridiculed people who “cling to guns or religion.”

There is a vigorous debate over the proper role of philanthropy and philanthropists in society, the value of common forms of giving, and how we think about charity. Far from being opposed to the role of charity and philanthropy, however, those who support the John Locke Foundation see “a North Carolina of responsible citizens, strong families, and successful communities committed to individual liberty and limited, constitutional government.” They want “to transform government through competition, innovation, personal freedom, and personal responsibility.” They seek “a better balance between the public sector and private institutions of family, faith, community, and enterprise.” This means not just shrinking government, but actively building those private institutions with their time, talents, and money, today and throughout the year.