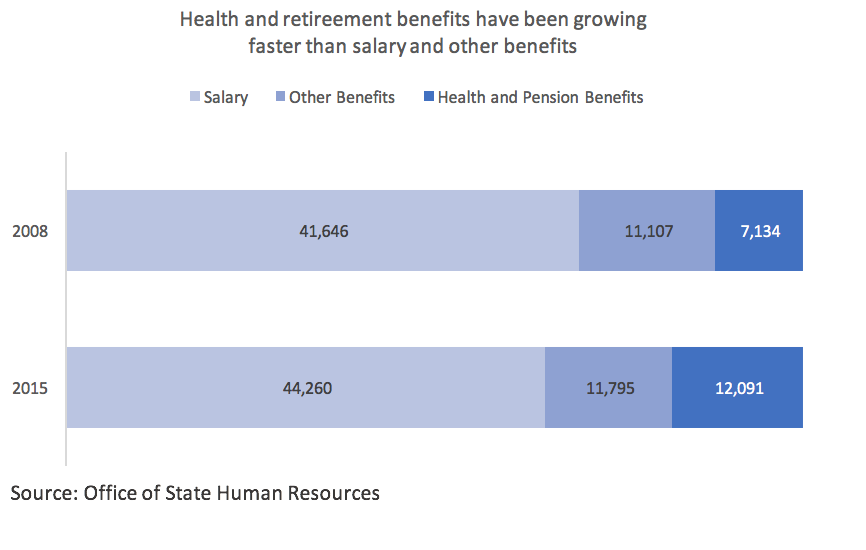

Pay for teachers and other state employees has generated headlines in news coverage of the budget this year, in part because there have been no legislative salary increases in five of the seven years between the start of the Great Recession in 2008 and 2015. As a result, salaries over that time grew at an annual rate of 0.7 percent, from $41,646 to $44,260. The emphasis on paychecks, however, misses the rest of the compensation story.

Employees receive a salary, paid leave, health insurance, contributions toward retirement, longevity pay, and the employer portion of Social Security. As one might expect, the fastest growing components of employee compensation were state-funded contributions to the retirement plan, to current health insurance coverage, and to the reserve for retiree health benefits.

Employer contributions to the state pension plan tripled, from $1,270 as of December 31, 2008, to $4,050 by December 31, 2015. Current insurance premiums increased by $1,407 over that time, from $4,156 to $5,563. Contributions to the Retiree Health Plan Reserve for the average employee increased 45 percent, from $1,707 to $2,479. Together, the growth in these three areas alone nearly doubled the increase in salaries – $4,958 compared to $2,614. As a result, employee benefits climbed from 30.5 percent of total compensation to 35.1 percent.

It would be a stretch to claim that slower growth in contributions to health insurance and retirement benefits would have gone directly to higher pay, but it is striking that nearly two-thirds of the increases in compensation for state employees between 2008 and 2015 were invisible. If anything, the most noticeable changes were unpopular reductions in the generosity of health insurance benefits, charges for more generous coverage options, and incentives for healthy behaviors. Were it not for those changes, even more compensation would have been hidden.

Despite these changes, state employees have generous health insurance benefits during their employment with the state and the promise of generous benefits when they retire. Generosity does come at a cost, however, one that will climb if the state is to fulfill its promises for health insurance and pension payments to future retirees.

A recent court decision curtailed the ability of the General Assembly and State Treasurer to ensure the future availability of promised benefits, overturning a 2013 policy that began to charge a premium for the most generous health insurance option in the State Health Plan. With less flexibility to adjust benefits for current retirees (and at least some current employees), the choice, at some point soon, could be to eliminate benefits for any future hires.

Like many of the programs they must administer, state employees’ pay and benefits are at once lavish and insufficient. Over the latter half of the twentieth century, elected officials made promises that could only be financed with rapid economic growth or high inflation. Growth would provide tax revenue, and inflation would reduce the value of financial obligations. A slow economy and low inflation make those promises less realistic. Salaries for state employees may increase, but their share of total compensation will likely continue to shrink, even as compensation for current employees shrinks as a share of total spending.