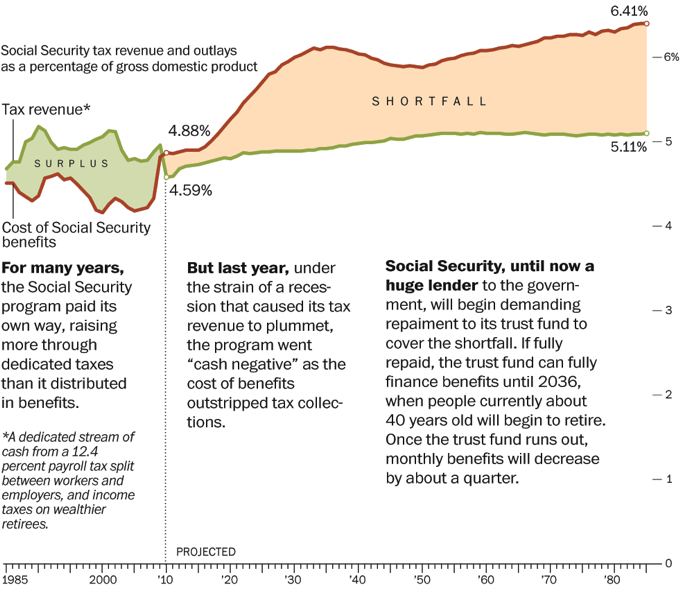

This weekend the Washington Post and Bloomberg released a chilling graphic for Social Security payments and receipts—even with the CBO’s more-than-rosy projections.

It demonstrates a shortfall as far as the eye can see, one that will perpetuate gargantuan deficits which ought not happen. Yet federal legislators appear reluctant to address this burgeoning gap. Higher levels of taxation are economically and politically infeasible, and a majority of House members have vowed against them anyway. On the other hand, political pressure to maintain or even expand Social Security payments is immense.

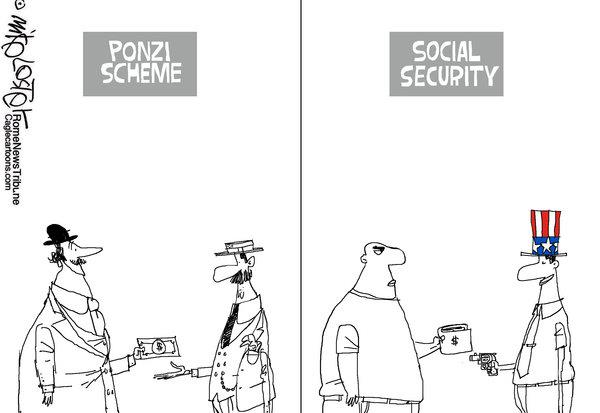

Whether we like it or not, we are coming to the end of the Ponzi scheme, and over time this reality is becoming evermore evident. Ponzi schemes, which do not set money aside but simply transfer it, fail when there are no longer enough people paying in to cover the payments going out. An aging baby-boom generation, along with greater longevity in general, has insured this outcome.

While I appreciate the Post‘s willingness to run the article and graphic, a few points of clarification merit mention. Social Security never “paid its own way,” and the supposed surplus in the graphic is misleading. The program brings in taxes and pays them out, either to Social Security recipients or federal officials spend the money. That might give the impression of revenues covering expenses, but that’s only if you ignore the acquired liabilities—the people paying in who expect and plan to be paid back—which are an expense, even if unaccounted for.

In other words, the money received came with an equal if not greater liability, and federal officials did not set money aside for that. That means the recession did not cause the shortfall; it has been building for generations. Right from the get go, Social Security was accumulating debt for the American taxpayer, and it continues to do so. In fact, Social Security is worse than a Ponzi scheme, since participation is mandatory, not voluntary.

For more on the mechanics of Social Security, the liabilities it generates, and what this means going forward, I highly recommend The Coming Generational Storm by Laurence Kotlikoff, a former professor of mine back at Boston University. Alternatively, check out this video. Although Kotlikoff gave this in 2004, the fundamental concerns remain the same, and given that seven years have passed, his words almost seem prophetic.