On August 12 the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) announced it had made “corrections to the state’s daily and cumulated completed COVID-19 test counts after discovering a discrepancy in testing data that had been submitted by LabCorp.” The discrepancy was in data submitted from April 24 until August 8.

The revision was not the agency’s first, however. It underscored an ongoing issue with the daily COVID-19 numbers DHHS reports on its dashboard.

People have been questioning for months an obvious discrepancy between the percentage of tests returning positive that DHHS states on its testing page and the percentage someone would get by dividing DHHS’s reported cases (positives) by reported tests. The problem was made worse because the agency did not report an accurate seven-day rolling average until August. While people on social media would make excuses for the agency, DHHS Sec. Mandy Cohen herself was never asked about it in press briefings or in testimony before legislators.

Despite DHHS’s many revisions, reported case numbers never changed. Everything else has — deaths, testing, hospitalizations, even the number of beds in hospitals. Also, tests reported on a particular day, hospitalizations on a day, hospital admissions on a day, and deaths have all changed not just up when more have been reported, but also down for unknown reasons. When DHHS changed its reporting standard in mid-July, the number of inpatient beds inexplicably jumped from 21,222 to 25,309, and the number of ICU beds jumped from 3,223 to 3,462. Since then, the number of ventilators in use and available has ranged from 3,156 to 3,377, presumably as some are in transition. DHHS made many significant changes in reporting with no explanation.

Again, for weeks the seven-day rolling average for the percentage of tests returning positive had no obvious connection to the daily reported ratio. DHHS’s reported ratio has regularly been higher than what the average person could calculate from the reported cases and reported tests on the DHHS dashboard. I submitted questions to DHHS staff and spoke with reporters at other news organizations trying to understand the difference. Other followers of the data would comment or ask me about it.

DHHS eventually provided a note that the percent positive was calculated on data from labs that submitted both positive and negative results electronically through the NC Electronic Data Surveillance System (NCEDSS). The agency later incorporated the paragraph in a more visible way, explaining that the percent positive was based on a “subset of all testing completed” totaling “approximately 70% of total tests in the last two weeks.” Here is a screenshot from June 30 of that paragraph:

Even today, DHHS states “Approximately 80% of total patient-level tests are now submitted electronically through NC EDSS. The other 20% that are manually submitted must then be hand-entered into NC EDSS,” which would explain some of the variance in past numbers. The agency explains that it has a separate “manual communications” process “to post the daily and cumulative report of total tests performed.”

DHHS has never provided the number of tests or cases reported electronically to compare what it now calls “aggregate testing data” and the total cases number.

DHHS blamed a “LabCorp data error” that was found in a “discrepancy between electronic and manual reporting” for the recently discovered overstatement of 200,000 tests since April 24. Brian Caveney, Chief Medical Officer and President of LabCorp Diagnostics, said the company submitted data “through both an electronic reporting system that is established through state regulations and a separate manual process as requested by NCDHHS” (emphasis added).

Based on DHHS’ description of its reporting process, every company that uses the electronic system must also manually report the aggregate number of tests. The agency has not explained why labs must provide manual data in addition to the patient-level data using the state’s electronic reporting system.

“Although this reporting error impacts our count of total tests completed,” Cohen assured us, “it does not alter our key metrics or change our understanding of COVID-19 transmission in North Carolina, which shows stabilization over the last few weeks.”

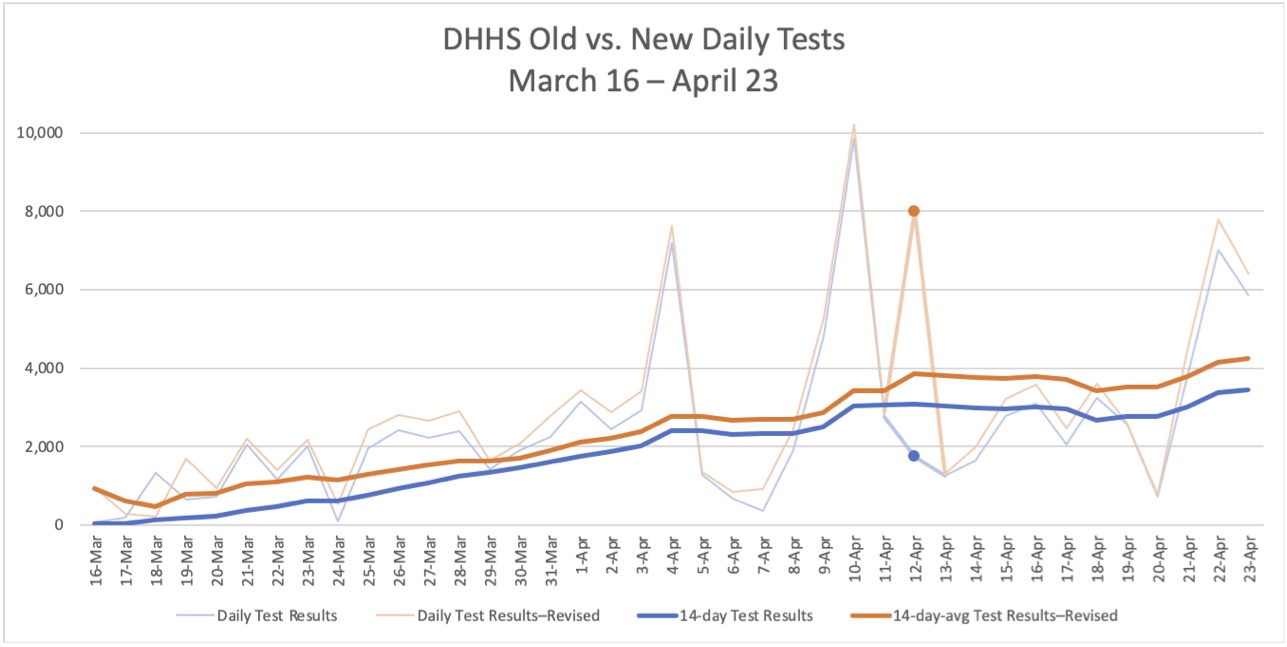

Oddly, DHHS revised its testing numbers back to March 16, well before the dates of the reported error. From that date through April 23, the new testing numbers are consistently higher than the old numbers. The two lines are similar except for a spike on April 12 to 7,999 in the revised test reporting, compared with 1,746 in the previously reported tests.

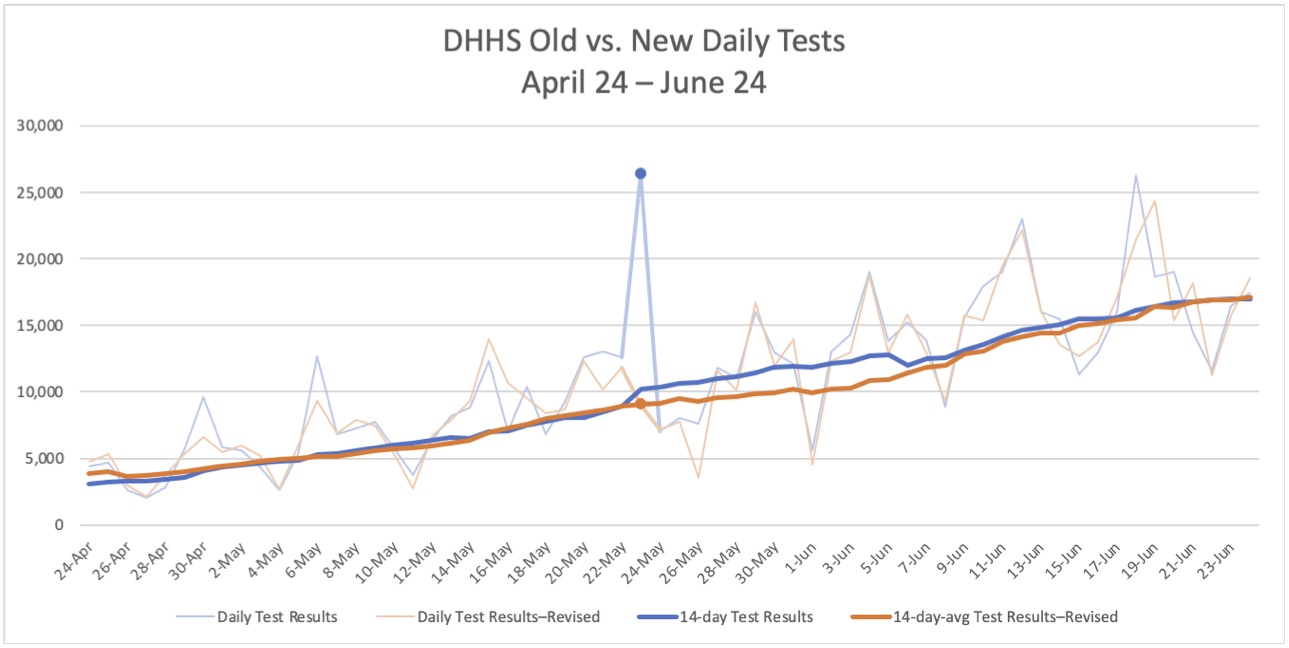

From April 24 through June 23, the only notable difference is on Saturday, May 23, the first day DHHS reported more than 1,000 cases for North Carolina. The number of tests reported that day originally was 26,358, twice as many as any previous date, and that number would not be equaled in the revised numbers until another 50 days later, on July 12. Aside from that spike and its continued effect on the 14-day average, the patterns are very similar for the first two months of the mishandled reporting.

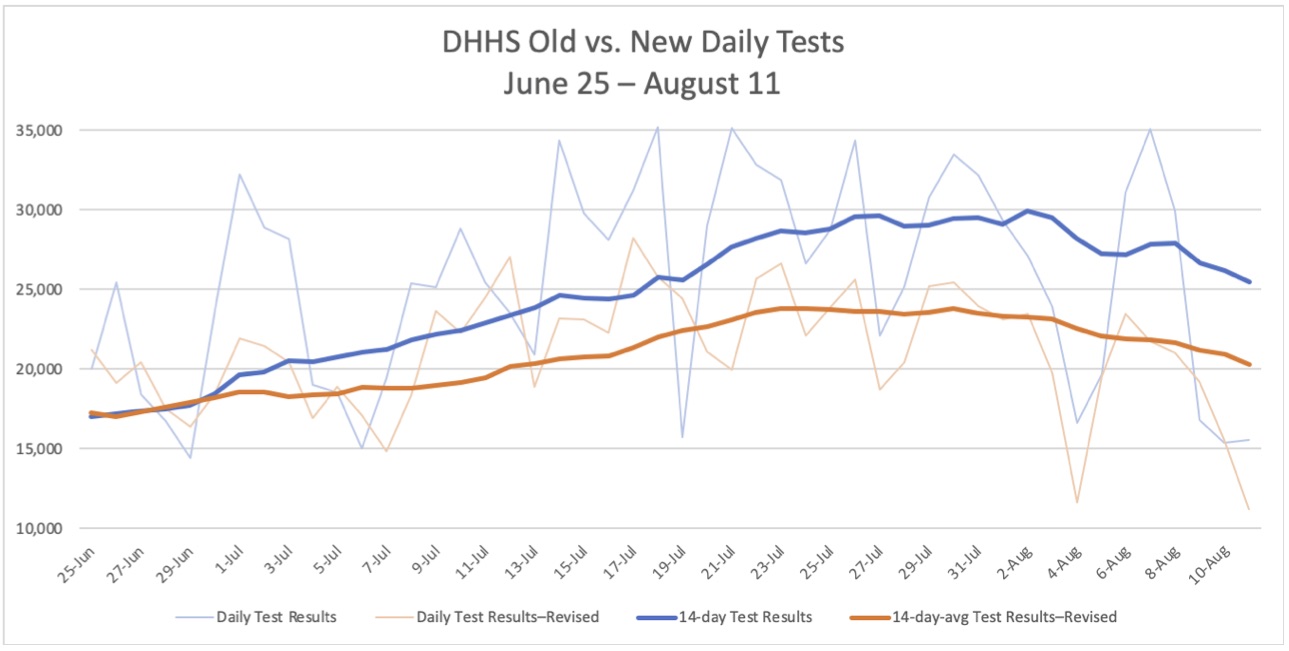

Not until July 1 do the previously reported numbers consistently exceed the revised number of tests, but then there is a large divergence. According to the old numbers, testing soared through the month of July, with 14-day averages of nearly 30,000 tests per day and multiple days with more than 35,000 tests reported. North Carolina looked like a praiseworthy example for its scale of testing.

With the revision, however, North Carolina fell to 24th among the states in tests per 100,000 people.

Unanswered questions and the need for more transparency

DHHS’s revision prompted several questions:

- Why were the numbers DHHS originally reported in March and April consistently below the number of tests DHHS reports now?

- If the problem was with LabCorp’s reporting, why were the first two months so similar? Were there no home tests from LabCorp?

- What caused the spike in the revised reports on April 12? What caused the spike in the old reports on May 23?

- It may make sense for DHHS to have a manual process for labs that for whatever reason do not use the electronic system, but why did the agency have separate aggregate and electronic reporting for companies like LabCorp that used the system?

If anything, the revision strengthens the case for greater data transparency that we at the John Locke Foundation have been making for weeks. National and international comparisons from Johns Hopkins University, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the COVID Tracking Project, and others rely on data from the states. The questionable double reporting methodology and repeated changes to data raise questions not only about North Carolina’s numbers, but also those from other states as well.

Opaque, incomplete, and inconsistent data undermine the claims that policy decisions are driven by “science and data.” Science is also revealing the cost of lockdowns on mental health, dental health, education, and inequality.

It is good that DHHS staff caught and fixed the problem with testing. Now DHHS leaders need to improve their processes and be more transparent. Then maybe there will be more trust in their science and data.