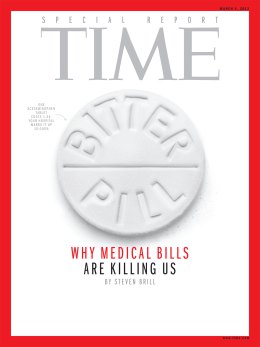

You might be surprised to learn that the latest TIME cover story devotes more than 24,000 words to diagnosing serious ills in American health care without offering effusive praise for President Obama’s 2010 federal health care reform law. But that’s not because the magazine sees the inherent problems linked to decades of government meddling in the health care sector.

You might be surprised to learn that the latest TIME cover story devotes more than 24,000 words to diagnosing serious ills in American health care without offering effusive praise for President Obama’s 2010 federal health care reform law. But that’s not because the magazine sees the inherent problems linked to decades of government meddling in the health care sector.

Instead, the article suggests the system would be much better if Medicare played a much larger role. As Richard Stengel spells out in his editor’s note: “If the piece has a hero, it’s an unlikely one: Medicare, the government program that by law can pay hospitals only the approximate costs of care. It’s Medicare, not Obamacare, that is bending the curve in terms of costs and efficiency.”

Yet that’s not the only way to interpret the facts. Take a section of the article with the subheadline “Medical technology’s perverse economics.”

Unlike those of almost any other area we can think of, the dynamics of the medical marketplace seem to be such that the advance of technology has made medical care more expensive, not less. First, it appears to encourage more procedures and treatment by making them easier and more convenient. (This is especially true for procedures like arthroscopic surgery.) Second, there is little patient pushback against higher costs because it seems to (and often does) result in safer, better care and because the customer getting the treatment is either not going to pay for it or not going to know the price until after the fact.

Beyond the hospitals’ and doctors’ obvious economic incentives to use the equipment and the manufacturers’ equally obvious incentives to sell it, there’s a legal incentive at work. Giving Janice S. a nuclear-imaging test instead of the lower-tech, less expensive stress test was the safer thing to do — a belt-and-suspenders approach that would let the hospital and doctor say they pulled out all the stops in case Janice S. died of a heart attack after she was sent home.

“We use the CT scan because it’s a great defense,” says the CEO of another hospital not far from Stamford. “For example, if anyone has fallen or done anything around their head — hell, if they even say the word head — we do it to be safe. We can’t be sued for doing too much.”

His rationale speaks to the real cost issue associated with medical-malpractice litigation. It’s not as much about the verdicts or settlements (or considerable malpractice-insurance premiums) that hospitals and doctors pay as it is about what they do to avoid being sued. And some no doubt claim they are ordering more tests to avoid being sued when it is actually an excuse for hiking profits. The most practical malpractice-reform proposals would not limit awards for victims but would allow doctors to use what’s called a safe-harbor defense. Under safe harbor, a defendant doctor or hospital could argue that the care provided was within the bounds of what peers have established as reasonable under the circumstances. The typical plaintiff argument that doing something more, like a nuclear-imaging test, might have saved the patient would then be less likely to prevail.

When Obamacare was being debated, Republicans pushed this kind of commonsense malpractice-tort reform. But the stranglehold that plaintiffs’ lawyers have traditionally had on Democrats prevailed, and neither a safe-harbor provision nor any other malpractice reform was included.

Rather than making a case for a larger government bureaucracy, the passage above suggests to this reader a prescription of medical malpractice reform and a much larger dose of consumer-driven health care.