Younger readers—i.e., those who have come of age since the inauguration of Bill Clinton—may find it hard to believe, but there was a time when the prime-time news wasn’t filled with lurid, tabloid-style accusations of sexual impropriety by political figures. That innocent period came to an abrupt end 25 years ago when, in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Anita Hill recited, verbatim, the sexually suggestive remarks that, she claimed, Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had made to her when he was her supervisor at the Department of Education and the EEOC.

As Maureen Down observed in Sunday’s New York Times:

Such vulgarities and sexually explicit language had never been heard before in the political arena. It was like a jackhammer drilling down into the most sensitive parts of the American psyche.

Like many feminists, Dowd takes it for granted that Hill was telling the truth:

Anita lost her fight. The creepy guy who acted pervy toward her won.

Nevertheless, in Dowd’s view, by “speaking truth to power” Hill accomplished something positive: she drew the nation’s attention to the serious problem of rampant sexual harassment in workplace:

That traumatic week in 1991 was … an important tutorial in sexual harassment….

Now we have been slimed with another week of unprecedented vulgarities and sexually explicit language in the political arena….

But this time, women get to vote. Thomas may have won his fight for a bigger job, but Donald Trump will lose. His alleged transgressions have energized women to support Hillary in a way that Hillary could not with her own campaign.

Dowd is probably right that Anita Hill’s testimony helped change Americans’ attitude towards sexual harassment (and it probably helped change the law of sexual harassment as well), but she is certainly wrong to assume that that testimony was true.

Writing at the Federalist, Mark Paoletta points out that:

Although Dowd does not mention it, Hill remains the only woman who has ever alleged that Thomas used such language in the workplace. That is far different from the typical sexual harassment case, or indeed any of the recent high-profile sexual harassment cases.

Common experience tells us that men who behave in this inappropriate manner do not just do it once. They victimize women over and over again. Yet after 25 years, Hill remains the only woman who claims that Thomas used pornographic language in the workplace.

Dowd also neglects to mention that the American people, after watching the Thomas-Hill hearings live—unfiltered by the media spin machine—believed Thomas. According to a New York Times/CBS News poll conducted several months after the hearings, “Americans still favor[ed] the judge’s confirmation to the Supreme Court by a ratio of 2 to 1.”

One of the key reasons Americans believed Thomas was the sheer number of women who came forward to defend him. Twelve of his former colleagues, including several who were Hill’s friends and colleagues, testified under oath that they did not believe Hill’s allegations and that Thomas would never say such lurid things. Indeed, Thomas had been through four previous FBI background checks, and no such allegations had ever surfaced.

The U.S. Senate voted to confirm Thomas because Hill’s story did not add up, and her testimony in front of the committee was riddled with lies. Try as she might, she could not explain away her decision to follow Thomas to another job after he had allegedly harassed her, or her repeated phone calls to Thomas over the years after she left government employment.

Her “corroborating witness,” Susan Hoerchner, found herself in the same boat, repeatedly backtracking on her testimony. Hoerchner told the committee staff, for example, that she was sure the harassment occurred in the spring or summer of 1981 before she left Washington, but Hill had not even begun working for Thomas at that time.

After discussing further discrepancies in the stories told by Hill and her supporters, Paoletta concludes:

To peddle the Hill story as if it were fact in spite of all evidence suggesting it to be fiction is the height of irresponsible journalism. To perpetuate this lie is as morally reprehensible as starting it in the first place.

This is the second time this month that Paoletta has come to Justice Thomas’s defense. Two weeks ago, in an article in the Hill, he complained that:

The National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened to much celebration and acclaim last month, bills itself as the “only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture.” …

Yet … the museum somehow has room for just a glancing negative reference to Clarence Thomas, the only black justice currently sitting on the United States Supreme Court, and only the second to ever do so. This is a shocking slight that the museum must redress.

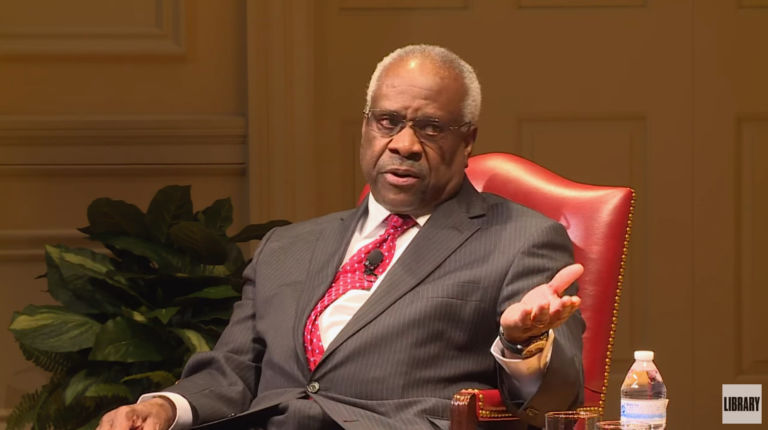

The slight is especially glaring because this month marks the 25th anniversary of his arrival on the Supreme Court. In that time, Justice Thomas has established a reputation as quite simply one of the most important legal thinkers of his generation….

It’s probable that the museum curators had no room for Thomas because his conservative views make him an “Uncle Tom,” as if arriving at different conclusions from his peers makes him an unsuitable topic for public conversation….

Surely a museum that “seeks to understand American history through the lens of the African American experience” should be more diverse than that.

Although Paoletta doesn’t say so, the “glancing negative reference” to Thomas occurs, ironically, as part of the museum’s prominent treatment of Anita Hill. The display that deals with the 1990s features several elements that present Hill’s story, including a photo accompanied by a back-lit sign that states:

In 1991 Anita Hill charged Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas with sexual harassment. This event transformed public awareness and legal treatment of sexual harassment. Outraged by Hill’s treatment by the all-white, all-make Senate committee, women’s groups organized, campaigning to elect more women to public office.

The museum’s neglect of what Clarence Thomas has achieved as a Supreme Court justice is inexcusable. Nevertheless, given her impact on the feminist movement and on the development of sexual harassment policies, its decision to include Anita Hill as an important African American figure is probably justified. But why stop there?

As many—including Maureen Dowd herself—have noted, “feminism died a little bit” during the Clinton administration as the county’s leading feminists rushed to defend a president who had been accused, not only of sexual harassment, but of sexual assault as well. If inspiring feminists to take a principled stand against sexual harassment justifies giving Anita Hill a prominent display at the Museum of African American History and Culture, then surely forcing those same feminists to abandon their principles justifies giving Paula Jones, Kathleen Willey, and Juanita Broaddrick a prominent display at the William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum!