Michael Beckley and Hal Brands place China’s negative actions in historical context.

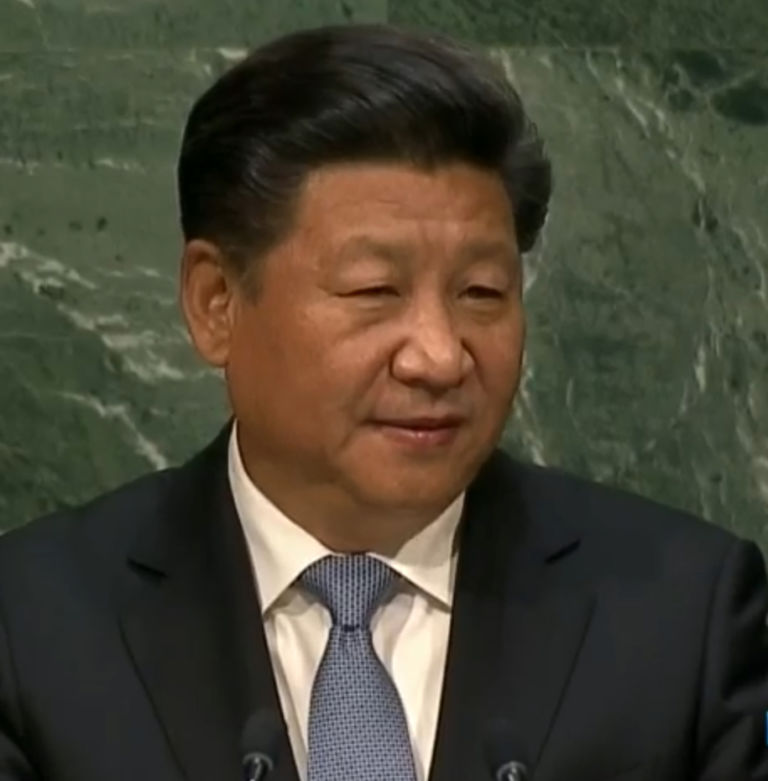

To grasp the Chinese challenge, we must grasp its ideological dimensions. If Woodrow Wilson and his followers wanted to make the world safe for democracy, the PRC’s rulers want to do the same for autocracy. For them, autocracy is not simply a means of political control or a ticket to self-enrichment, but a set of deeply held ideas about the proper relationship between rulers and the masses. In his October 2022 keynote speech to the Twentieth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—during which he had himself installed for a third term as top leader, while on the final day having his predecessor Hu Jintao unceremoniously escorted out of the room—Xi Jinping insisted that “constantly writing a new chapter in the Sinicization of Marxism is the solemn historical responsibility of contemporary Chinese communists,” and made it clear that “the authority of the Party Central Committee” will continue to be at “the core of leadership in controlling the overall situation.” Everything in the speech hinges on the CCP remaining in sole charge of “developing socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

This belief in the superiority of an autocratic Chinese model coexists with deep insecurity: The PRC is a brutally illiberal regime in a world led by a liberal hegemon, a circumstance from which the CCP draws a sense of pervasive danger and a strong desire to refashion the world order so that the PRC’s particular form of government is not just protected but privileged. That is why a powerful but anxious Chinese regime is now engaged in an aggressive effort to make the world safe for autocracy and to corrupt and destabilize democracies. Democracy promotion may be out of style in U.S. foreign policy, but what the scholar Jason Brownlee calls “democracy prevention” is very much at the heart of Chinese strategy today.