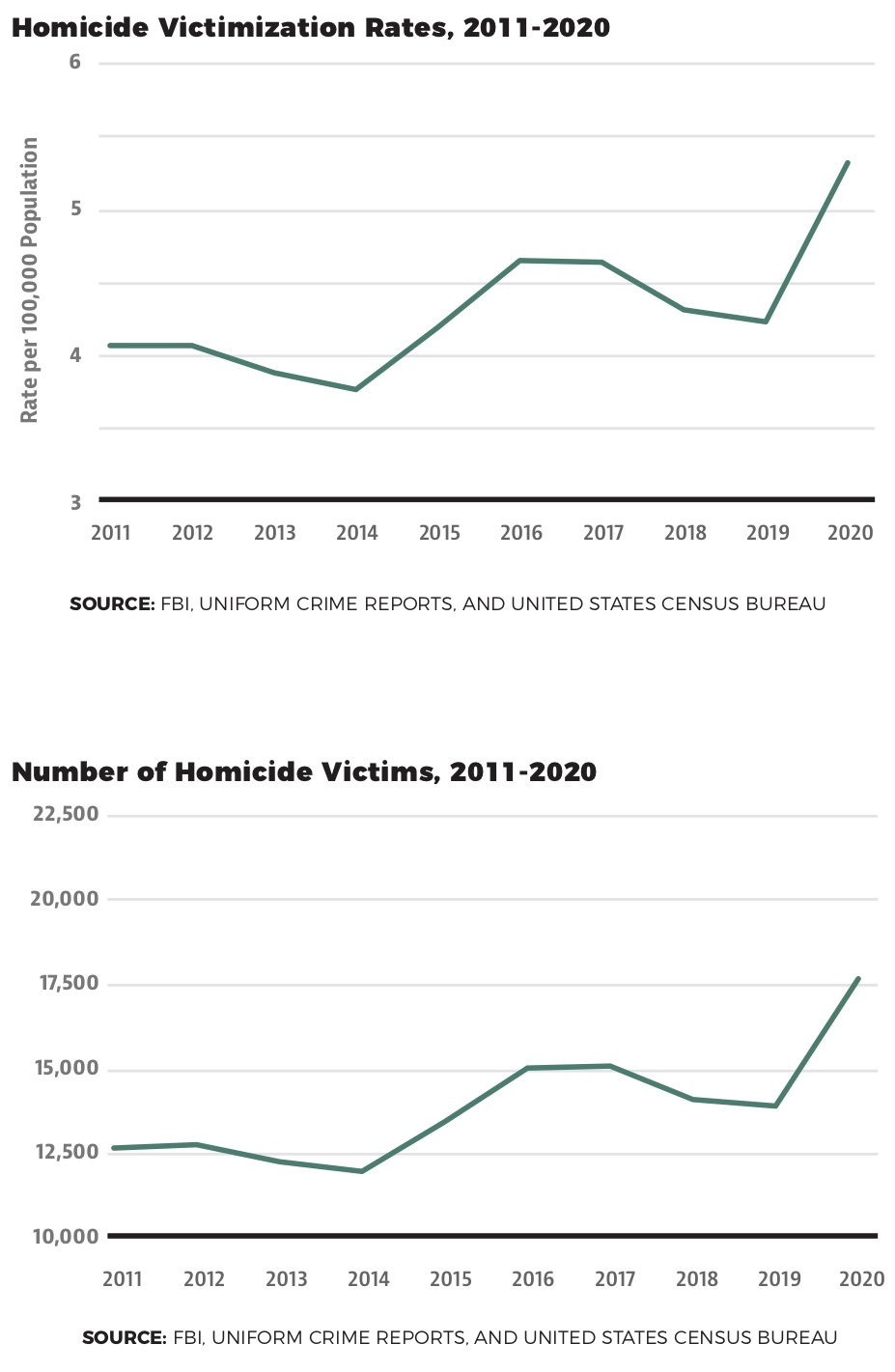

- Violent crime has spiked over the last year and a half, due at least in part to the hundreds antipolice protests that took place in the second half of 2020

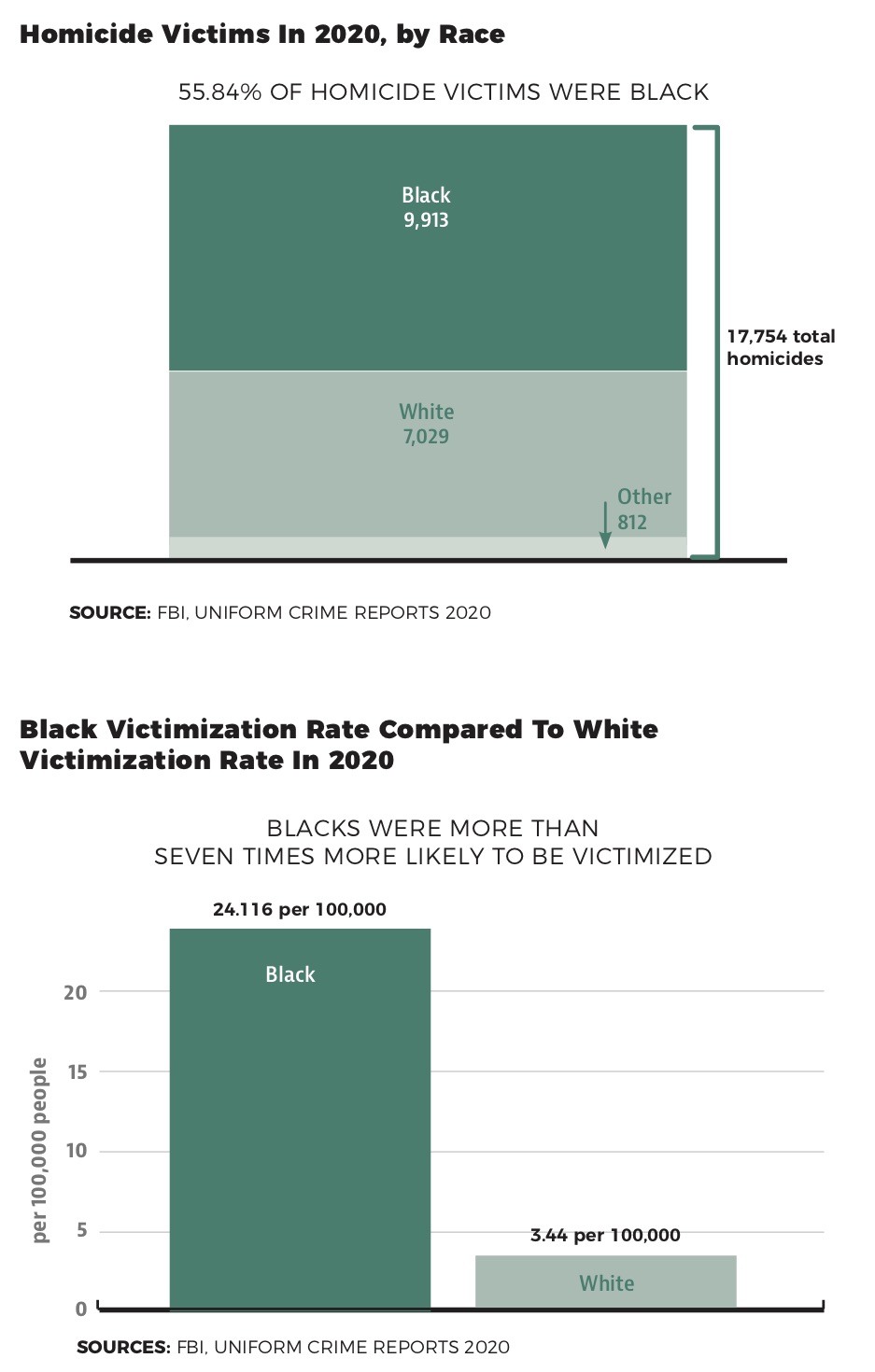

- This spike in crime has already inflicted a disproportionate amount of harm on Black Americans and the poor

- Unless steps are taken to bring the crime wave under control, Blacks and the poor will continue to be harmed for many years to come

As noted in the first installment in this series, the violent antipolice protests that took place in the second half of 2020 led to a precipitous spike in violent crime, especially homicides. By driving away investments and jobs, they also exacerbated the cycle of poverty in the communities in which they occurred.

Ironically, despite the protestors’ frequent invocation of the “Black Lives Matter” slogan, most of those who were harmed by the protests — most of the crime victims and most of the residents of the impoverished communities — were Black. Adding to the irony, at the very time when those antipolice protests were erupting across the country, research about previous antipolice protests was being published that made the deleterious effects of the new round of protests entirely predictable.

In June 2020, the National Bureau of Economic Research published a working paper called “Policing the Police: The Impact of ‘Pattern-or-Practice’ Investigations on Crime” by Harvard University economists Tanaya Devi and Roland G. Fryer Jr. The authors compared crime levels in 27 cities before and after investigations of police misconduct. In 22 of those cities, the complaints that led to the investigations did not receive much national media attention. Investigations in five other cities, however — Baltimore, Chicago, Cincinnati, Riverside, California, and Ferguson, Missouri — were triggered by what the authors called “viral” incidents; i.e., incidents in which the use of deadly force against a Black civilian “caught national media attention and the cities witnessed protests and riots soon after.”

Devi and Fryer found that the 22 investigations that were not preceded by viral incidents led to small reductions in homicide and total crime. “In stark contrast,” they wrote:

…all investigations that were preceded by “viral” incidents of deadly force have led to a large and statistically significant increase in homicides and total crime. We estimate that these investigations caused almost 900 excess homicides and almost 34,000 excess felonies. The leading hypothesis for why these investigations increase homicides and total crime is an abrupt change in the quantity of policing activity. In Chicago, the number of police-civilian interactions decreased by almost 90% in the month after the investigation was announced. In Riverside CA, interactions decreased 54%. In St. Louis, self-initiated police activities declined by 46%.

In short, violent antipolice protests in those five cities led to a decrease in police presence that, in turn, resulted in 900 excess homicides and 34,000 excess felonies. Moreover, additional research using different methods suggests a full accounting of crime increases following antipolice protests during that period would yield numbers that are even higher.

In another 2020 study, “Public Scrutiny and Police Effort: Evidence from Arrests and Crime After High-Profile Police Killings,” Deepak Premkumar of the Public Policy Institute of California compared policing effort in 2,740 police departments, 52 of which experienced at least one high-profile officer-involved fatality between 2005 and 2016. In the 52 departments that experienced high-profile officer-involved fatalities, Premkumar found that reduced police effort led to “a significant rise of 10–17% in murders and robberies” as well as “smaller increases in property crime, driven by theft,” and in the departments that experienced the highest-profile deaths — “ones that generate at least 5,000 articles of coverage” — Premkumar found “increases of 27% in murder, 11% in aggravated assault, and 12% in burglary.” With casual academic understatement, Premkumar concluded by observing, “high-profile, officer-involved fatalities impose tremendous crime costs on the involved jurisdictions.”

In May 2021, University of Massachusetts at Amherst doctoral student Travis Campbell published a study of more than 1,600 Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests that took place between 2014 and 2019. He found that the use of lethal force by police fell by 15.8% following BLM protests, and that “a decrease in encounters [due to reduced police effort] drove the lethal force reduction rather than a change in use-of-force propensity.” He also found that “civilian homicides increased by 10% following protests,” also due to reduced police effort. Campbell did not provide an estimate of the number of excess homicides caused by BLM protests, but as Jerusalem Demsas observed in a discussion of Campbell’s findings at Vox, “That means from 2014 to 2019, there were somewhere between 1,000 and 6,000 more homicides than would have been expected if places with protests were on the same trend as places that did not have protests.”

Any way one looks at those findings, it seems clear that antipolice protests led to thousands of excess homicides between 2005 and 2019. Moreover, while the authors of those studies didn’t provide any details about the victims, given the demographic makeup of the cities themselves and differential crime rates in general, we can be quite sure that those victims were disproportionately Black and poor.

Nor is the direct suffering of those victims and their families the whole story. Following the pattern described in my discussion of the late 20th century crime wave, those excess homicides and other crimes coming on top of the often violent protests that preceded them undoubtedly harmed all of those cities’ residents by depressing property values and discouraging investment and job creation, and there can be little doubt that the burden of those harms fell most heavily on Blacks and the poor.

Given those findings from previous years, it’s no surprise that the hundreds of violent antipolice protests that took place in 2020 made both crime and the indirect harm it causes worse in the short run. If lawmakers public safety officials want to ensure that the protests don’t make crime and the indirect harm it causes worse in the long run as well, they need to do something quickly to bring crime under control and restore public order.

Fortunately, as future installments in this series will explain, there’s a humane and cost-effective way to do that. Intensive community policing — i.e., the strategic deployment of large numbers of well-trained and well-managed police officers in high-crime, high-disorder neighborhoods — is a humane and cost-effective way to deter crime.

For additional information, see:

Black Lives Matter – Which Is Why We Need More Police Funding, Not Less

The Late 20th Century Crime Wave Was a Disaster for Blacks and the Poor

How America Ended Up Underpoliced and Overincarcerated

Prominent leftist suddenly sees that violence is bad, but for the wrong reason