- North Carolina reportedly had a record year of investment in film productions in 2021 despite having a cap on its film grant, a seemingly counterintuitive result, but one that’s consistent with research on film incentives

- Owing to so many other factors influencing film productions, research has found film incentives have diminishing returns and argued for strictly limiting the incentives even if they’re to grow the film industry as opposed to the state’s overall economy

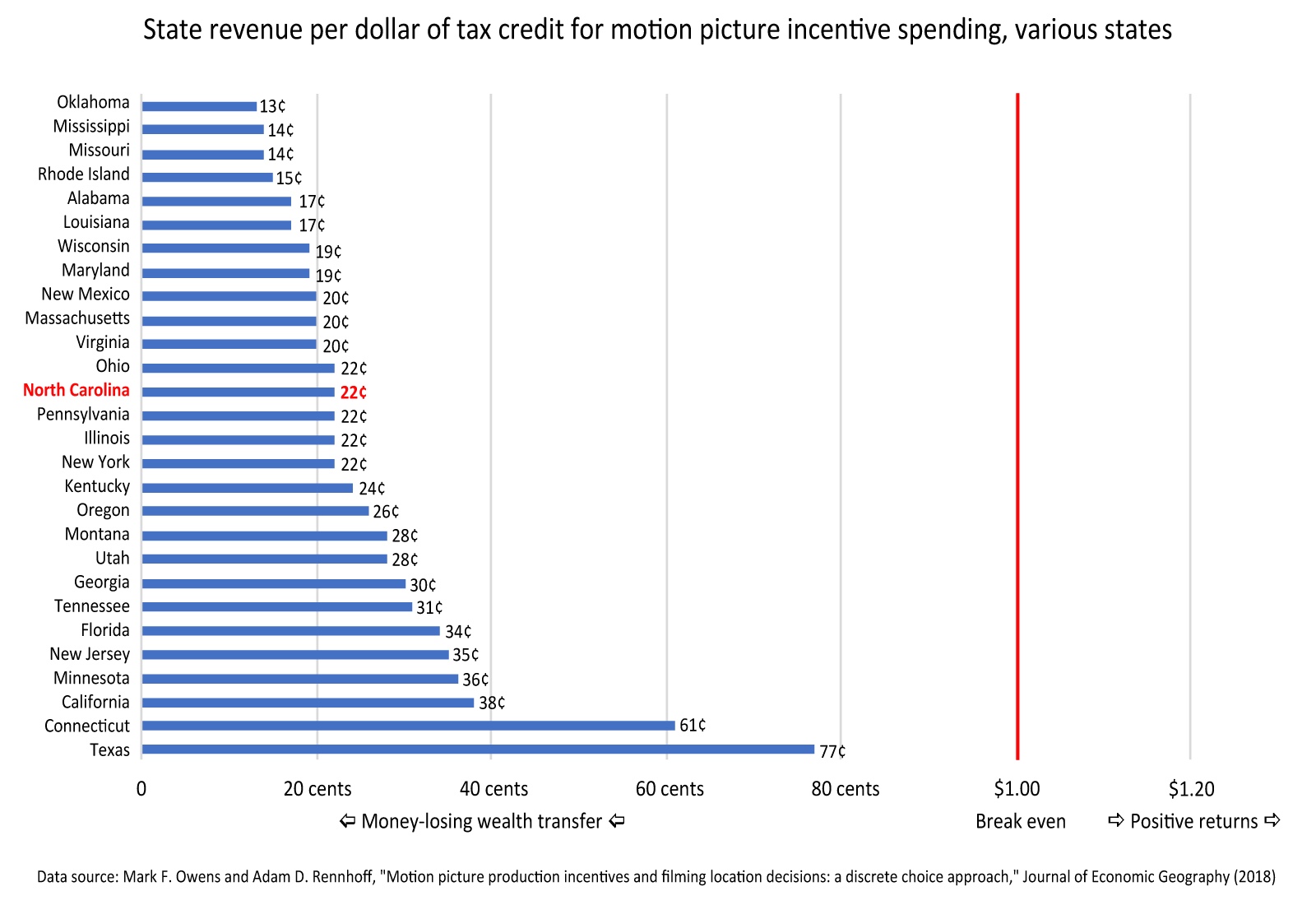

- Research also finds that film incentives fail at growing a state’s economy, returning only cents per dollar of tax credit or grant given

North Carolina’s film industry has attracted a record high of investment this year, according to Gov. Roy Cooper. A gubernatorial press release states that expected investment this year will be $409 million.

Supposedly the hero of this story is the state’s film grant program. But a closer look at the numbers would show that the real hero has been North Carolina all along. “Several features make North Carolina an attractive location for filming,” we have long noted. “It offers a diverse climate, rural to urban landscapes, mountainous to coastal terrain, a cornucopia of settings, and a good production infrastructure. It’s also a right-to-work state with competitive wages and cost of living.”

In fact, the numbers announced fall right in line with the findings of economic research that called for a very limited if any film incentive program.

The press release noted:

This new in-state spending figure eclipses the state’s previous record of $373 million from 2012, when “Iron Man 3,” “We’re The Millers,” “Revolution,” “Homeland” and “Banshee” lensed in the state.

Bear that figure in mind, and let’s discuss research by one of the nation’s top scholars in film incentives, Kennesaw State University economist John Charles Bradbury. In 2018, Bradbury decided to research the following: Suppose a state decides to implement film incentives not thinking it will do anything for the overall economy, but solely to grow the film industry within the state. How generous should that incentive be?

The wisdom of starting from the perspective of just growing the film industry is that film incentives programs are well-known money losers for the states. They habitually return only cents per dollar of tax credit (or grant) given, which means they are wealth transfers, not economic development engines.

A program with diminishing returns amid many other contributing factors should be strictly limited

Bradbury found only a weak association between film incentives and growth in the film industry. It’s not that film incentives make no difference for the state’s film industry, it’s just that they are only one out of a host of factors that affect film production location choices. There’s a level of tax credits associated with the industry’s in-state growth, but they have diminishing returns, so offering incentives beyond that level offers no association with any further industry growth.

Bradbury found (emphasis added):

Film credits of ten-percent or greater are associated with increased film industry growth; however, raising the credit to a higher level is not associated with further industry growth. States that seek to subsidize the film industry to boost its in-state presence for non-economic reasons—perhaps state residents receive non-pecuniary benefits from having movie stars travel to the state—can attain those benefits with lower levels of tax credits. The estimates indicate that extending the credit to higher levels is not associated further the growth of the film production. …

If greater tax credits do not encourage further film production, then they represent an increased transfer to film producers without any corresponding benefit from increased economic activity.

So this brings us back to this year’s banner year versus the previous high of 2012. How much did the state give in film tax credits in 2012 for $373 million in investment related to the film industry?

The answer: $84.8 million, per the North Carolina Department of Revenue.

What about this year, for $409 million in investment? Thanks to the General Assembly converting in 2014 the open-ended Film Production Tax Credits to a budgeted Film and Entertainment Grant, North Carolina has not spent as much on film incentives. The annual budget for the Film and Entertainment Grant is capped at $31 million.

The cap means that even though North Carolina exceeds Bradbury’s level limit of rebating 10% to qualifying film productions (our level is 25%, with maximum credit limits), the overall limit is keeping the state from losing more money on a revenue-losing money transfer than otherwise. Again, Bradbury’s level was just on how to grow the film industry, not grow the state’s economy (something film incentives can’t do).

Still, having a cap on the film grant hasn’t harmed film production in North Carolina. That’s for the simple reason that film production in North Carolina was never a product of government incentives.

What film incentives can’t do

If, however, state leaders think beyond use of film grants to grow the film industry, and instead consider it on its merits of whether it grows the state’s economy, they might consider repealing the program altogether.

There are many things that film incentives can’t do:

- They can’t be shown to boost a state’s economy

- They can’t be shown to work as an economic-development tool

- They can’t prevent a rent-seeking, extortive political economy

- They can’t be much more than a giveaway to outside film production companies

- They can’t do much even to boost just the state’s film industry

- They can’t prevent intended recipients from threatening to refuse the incentives as a way to extort social policy choices that align with their own political preferences

- They can’t make your favorite North Carolina movie that was made many years before film incentives the reason to have film incentives

Incidentally, Bradbury studied North Carolina’s film incentives specifically. In a 2019 study for Western Carolina University’s Center for the Study of Free Enterprise, Bradbury asked “What Do Film Incentives Mean for North Carolina’s Economy?”

“North Carolina’s film incentives, which have cost the state over $400 million, do not appear to have delivered the promised economic boost,” Bradbury found (emphasis added). “For this reason, policy makers may wish to reconsider the state’s commitment to the incentives.”