The debate over adjustments to North Carolina’s General Fund budget is heating up amid proposals from the governor, House, and Senate. All three, however, push in one direction: more spending than planned.

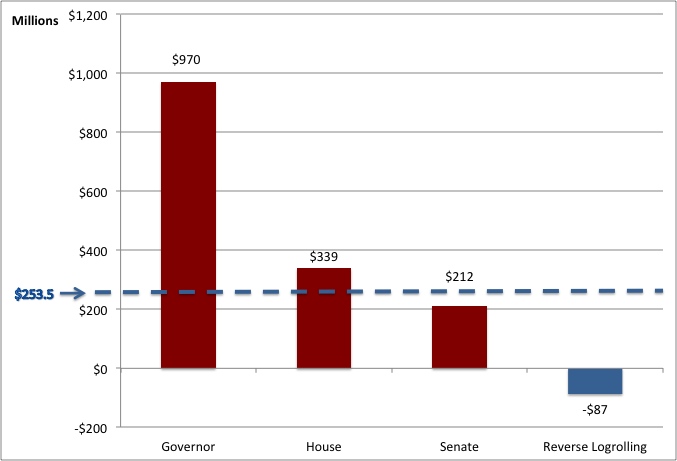

Legislators may claim that revenues have been beyond earlier projections, so there is more money available. That is correct; the Fiscal Research Division of the legislature now projects an additional $253.3 billion of revenues over the 2012-2013 two-year period.

As you can see from the diagram, though, the reaction has been a resounding, "Let’s spend it!" Both the House and governor’s proposals would spend even more than the surplus brought in, and the Senate proposal spends 84 percent of it.

By comparison, legislators could easily reduce spending, as noted by the blue bar. For each component of the General Fund, the reverse logrolling approach takes the lower of the Senate and House proposals and combines them for a total budget. (I’ll be releasing a more detailed explanation of this analysis in the next couple of days.)

Proposed General Fund Adjustments for Fiscal Year 2013

Short of the reverse logrolling’s reduced spending, even simple continuance of the current General Fund spending plan would allow dollars to be set aside for the state’s paltry Rainy Day Fund of less than $300 million. Similarly, General Fund spending could be less reliant on nonrecurring revenue sources. Otherwise, the remaining money would be available to assist with tax reform in the next session.

But recent legislator actions, essentially all in the direction of higher spending, speak for their priorities louder than words can.

All balanced budget amendments are not created equal

Last week, I mentioned the Independent Institute‘s journal, The Independent Review, for its concise overview of the impact of different institutional constraints on government spending. This week, let’s examine the authors’ claims about the effectiveness of balanced budget amendments.

Matthew Mitchell and Nick Tuszynski note that 49 of the 50 states have a balanced budget requirement, but a majority of those have no teeth. Three key attributes appear to be necessary for a "strict" requirement. They "emerge consistently as being statistically significant," Mitchell says:

- The final budget, voted on by the legislature, is the one that must be balanced, not an earlier version;

- There can be no allowance for deficits to be carried over. They must be resolved that year;

- An independently elected judiciary must enforce these requirements.

Fortunately, North Carolinians possess such protections. Keep that in mind with regard to the elected judiciary. One of their chief roles is to keep the executive and legislative branches in check. If that happens, the article’s authors assert $196 to $202 savings in per capita state spending.

Notes

- The John Locke Foundation hosts many insightful speakers, and I encourage readers to come along to our events. One in particular that stood out of late was with Lawrence Lessig, author of Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress — and a Plan to Stop It. While I don’t agree with all he advocated, his message that we can work against the common enemy of corruption, particularly at the federal level, is worth considering. He even promoted an Article V amendments convention. Yes, it is a bipartisan idea.

- As some of you may already know, I am highly active on Twitter and glad to engage with more people through that medium. If you would like to follow me, my username is @FergHodgson (si prefiere espanol @Fergusito).

Click here for the Fiscal Insights archive.