Gov. Cooper’s risky bet to keep spending like it’s 2019, despite a $1.6 billion loss of revenue between March and the end of June, is reckless and irresponsible with taxpayers’ money. It is part of a pattern for Cooper and contrasts unfavorably with the actions of former governors Mike Easley and Bev Perdue in similar situations.

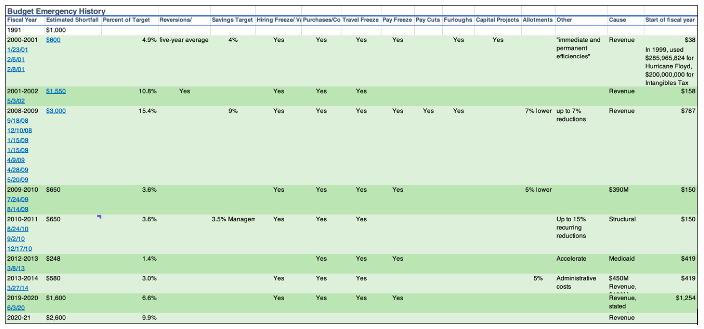

Easley raised the sales tax by a half-cent in 2001, then extended the tax increase in 2003 and 2005, and Perdue raised the sales tax by a full penny in 2009. Before either governor raised taxes, they took steps to rein in spending and keep the budget balanced with targets for agency savings. Instead of such sensible steps, Cooper plans to spend down the $2.1 billion (as of May 31) cash balance and count on more federal money either through flexibility for money Congress already provided or through another round of federal bailouts to states.

In a June 3 budget memo to state agencies, State Budget Director Charles Perusse wrote, “As we estimate revenues, including the FY 2019-20 cash balance, additional federal stimulus support, and monies in the Savings Reserve Account (as a last resort), we anticipate that the state would remain in balance and could support this current budgeted spending level.” Perusse anticipates “additional federal stimulus assistance” to get through FY 2020-21 despite an even larger $2.6 billion revenue shortfall.

This is not why the John Locke Foundation began working with 28 other state think tanks to advocate flexibility with $4 billion Congress provided to North Carolina state and local governments through the Coronavirus Relief Fund.

Since 2011, North Carolina government has budgeted responsibly. Appropriations per person were set to be $30 lower this year, adjusted for inflation, than in 2011. With $1.1 billion in savings, a cash balance of $2.2 billion in February, and a mix of short-term and permanent spending reductions, federal assistance would have put North Carolina in a good position to weather the economic downturn and still have money available in case of another major hurricane.

Instead, Cooper waited 37 days from his order closing restaurants and bars on St. Patrick’s Day until an April 23 memo ordering “budget management measures.” Even then, the reductions only covered pay, new hiring, new purchases, and travel. In contrast, within a month of his 2001 inauguration, Easley had issued orders for spending reductions, larger reversions of allotted funds, furloughs, and “immediate and permanent efficiencies.” The next year, faced with an even larger shortfall after increasing the sales tax by a half-cent, Easley again ordered agencies to plan reversions and other cost-saving measures. Easley and Perdue issued seven budget memos and executive orders from September 18, 2008, through May 20, 2009, instituting a number of cuts, including a 7% reduction in allotments to agencies and pay cuts and furloughs for state employees. They took these steps even as the federal government sent $680 million to the state, and Perdue scraped $802 million from various funds across state government.

They dealt with grave problems with something approaching the appropriate gravity. We at the John Locke Foundation thought they could have done even more to reduce spending instead of raising taxes, and we provided examples in alternative budget proposals over the years. We also disagreed with how Perdue encouraged school districts to pay teachers with one-time federal money. Despite those decisions, the two prior governors did reduce spending in a way Cooper has been unwilling to do.

Cooper’s steadfast commitment to maintaining spending is another indication of his willingness to shift responsibility and “to raise taxes if Democrats regain a legislative majority in November or force a newly-elected Gov. Dan Forest to make deep cuts.”