- Multimember districts for the North Carolina General Assembly were once common but were struck down over how they diluted minority voting strength

- Multimember districts disconnect representatives from their constituents

- Multimember districts force voters to consider many more candidates, making ballots more confusing

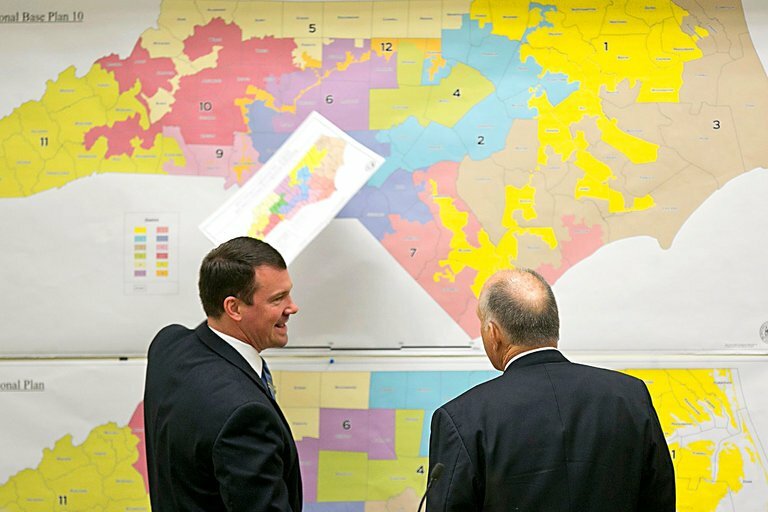

When I previously wrote about standards that should guide legislative redistricting, I included standards such as compactness and not using political data. One standard I did not mention was that we should not use multimember districts.

Multimember districts had long been an established part of legislative representation in North Carolina, so it is worth reviewing why North Carolina stopped using them and why they should not come back.

Why North Carolina No Longer Has Multimember Districts

North Carolina had long had multimember districts, using them primarily to assign multiple legislators to larger counties to have more equal representation between those living in more populous and less populous counties.

Black political leaders began advocating against the system they believed was “diluting their voting strength within large, multimember districts” (North Carolina Insight, December 1990, page 36) in the 1980s. They found allies in Republicans who similarly believed that multimember districts disadvantaged them by submersing their supporters into larger groupings of Democrats. Their collective efforts in the legislature and the courts reduced the number of multimember districts in the state over the next two decades.

A landmark redistricting case in 2002 dealt the final blow to multimember districts in North Carolina. The North Carolina Supreme Court found in Stephenson v. Bartlett that the redistricting plan the state adopted in 2001, which contained both single-member and multimember districts, was unconstitutional. From page 39 of the ruling:

In our view, use of both single-member and multi-member districts within the same redistricting plan violates the Equal Protection Clause of the State Constitution unless it is established that inclusion of multi-member districts advances a compelling state interest.

The court’s reasoning was that, even though the districts were proportional, voters in multimember districts could vote for several representatives while voters in single-member districts could vote for only one.

No compelling state interest for multimember districts was found in subsequent hearings.

While Stephenson v. Bartlett precludes the use of multimember districts in a redistricting plan that also includes single-member districts, it does not preclude them outright. A plan incorporating equally sized multimember districts could pass muster under Stephenson. For example, the General Assembly could create a set of 24 five-member districts for the 120-member North Carolina House of Representatives.

While such a plan would be allowed under Stephenson, it would create problems.

Multimember Districts Disconnect Citizens from Their Legislators

The first problem with multimember districts is that they create distance between legislators and their constituents and cause confusion over representation.

In single-member districts, citizens know which legislator to call when they have a problem with government. In addition, each legislator represents the smallest possible constituency. That combination of clear responsibility and smaller constituencies creates stronger ties between legislators and constituents. A 2006 study found that single-member districts “increase incentives for legislators to provide constituency service.”

By comparison, in systems in which citizens are represented by numerous legislators in the same district, there is less of a connection between citizens and legislators. The U.S. Supreme Court recognized that as a weakness of multimember districts, stating in Chapman v. Meier (1975, pp. 15–16) that “when candidates are elected at large, residents of particular areas within the district may feel that they have no representative specially responsible to them.”

Single-member districts avoid that problem.

Multimember Districts Make Ballots Confusing and Weaken Minority Voting Strength

Then there is issue of how citizens would vote in multimember districts.

For those citizens who wish to evaluate candidates before voting for them, their task would grow with each additional seat in a multimember district. While citizens must evaluate two or three candidates in most contested races in single-member districts, those in five-seat, multimember districts would have to evaluate between ten and fifteen candidates. The U.S. Supreme Court found in Chapman that, under such systems, “ballots tend to become unwieldy, confusing, and too lengthy to allow thoughtful consideration.”

The North Carolina Supreme Court agreed with that assessment in Stephenson v. Bartlett and noted the concern expressed by black and Republican leaders two decades earlier: multimember districts suppress minority voters (page 35):

[V]oters in multi-member districts invariably suffer the adverse consequences described by the United States Supreme Court: unwieldy, confusing, and unreasonably lengthy ballots; and minimization of minority voting strength.

To illustrate how multimember districts weaken minority voting strength, we can see the relationship between election method and party representation in North Carolina’s county commissions, using data from the North Carolina Association of County Commissioners. Of North Carolina’s 100 counties, 63 election all of their commissioners at large — each being essentially a single multimember district with all of the county being the district. Of those 63 counties, 48 (76.2%) have all commissioners from only one party. Of the 37 counties that do not elect all their commissioners at large, only four (10.8%) have all commissioners from the same party. With results like that, we can see why the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down multimember districts.

While there are methods to help reduce the “minimization of minority voting strength,” there is no method that would reduce the problem of “unwieldy, confusing, and unreasonably lengthy ballots” associated with multimember districts.

While General Assembly could legally create multimember legislative districts, there is no reason they should.