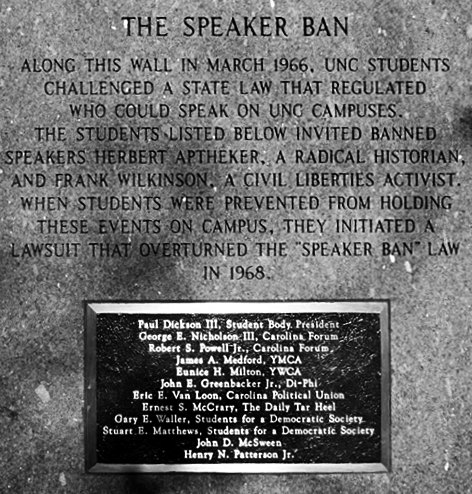

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has a proud history of supporting free speech and expression. One of the proudest moments in its history — and justifiably so — is how the entire university community fought the infamous Speaker Ban Law of the 1960s. There is a marker on campus to honor that fight and remember.

In the 1960s, the forces trying to silence unpopular speech came mostly from outside the campus. Now those forces are mostly on campus. The sources of the threat can change, but their goal is always the same: to prevent the airing of certain ideas, beliefs, even questions. Their effect would be the same even if the content of those forbidden ideas differ.

Stifling free speech and expression is counter to the genius of a free state. If possible, however, it is an even greater offense to the genius of a university. It is an abject betrayal of the spirit and pursuit of academic inquiry.

For these reasons and more, I am encouraged by the resolution “On Principles for the Promotion and Protection of Free Speech” adopted this month by the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It is a vigorous defense of free speech for the right reasons.

As reported by Carolina Journal,

The document is based on the “Chicago statement,” a set of guidelines laid down in 2015 by the Committee on Freedom of Expression at the University of Chicago.

“The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is committed to the production and dissemination of knowledge through open inquiry and the fearless exchange of a wide-range of ideas,” the resolution states. “The ability to speak freely, debate vigorously, and engage deeply with differing viewpoints is the bedrock of our aspirations at Carolina. As the oldest state university in the country, with a long and complex history, we are ever aware that speaking out on controversial issues often raises opposition and efforts to silence the outspoken.”

While the resolution is itself not policy and therefore not enforceable, it sets the tone, as CJ points out. The resolution is a strong moral declaration that recognizes that freely expressing ideas is irrevocably linked to a university’s ultimate mission to educate.

A timeless principle with many enemies

As a testimony to the timeless nature of this principle, consider how seamlessly its explication today meshes with its frequent invocations five decades ago against the Speaker Ban Law.

For example, the Faculty Council issued a statement on October 23, 1963, that “We believe that a university campus is a place where any idea should be open to free discussion.” The faculty then declared “the danger to a free society from abuse of free speech is not nearly so great as the danger from attempting to curtail or suppress free speech.”

Chancellor William B. Aycock gave a speech on June 6, 1960, entitled “Freedom of the University.” He warned against allowing the university’s freedom “to be infringed upon by an individual or group from whatever position or by whatever disposition.”

Aycock also said “it would be far better to close the university than to let a cancer eat away at the spirit of inquiry and learning.”

A UNC Student Government resolution of February 10, 1966, declared that “The university must serve as an open forum for different views and opinions, no matter how unpopular or divergent.” Among other things, the resolution also held that “The University must guarantee to all members of the academic community the right to hear all sides of issues,” and that “It is only through the critical examination of all alternatives that the accumulated knowledge of society can be advanced.”

It is not lost on this observer that the faculty are defending this principle now when they presumably are in profound disagreement with the ideas often subject to suppression at this moment in time. They issued this resolution despite well-known passions within academe and presumably on campus to suppress certain kinds of speech. Those passions have produced the malicious byproduct that defending free speech in the abstract is the same as agreement with and advocacy of the worst ideas.

In short, the university needs this return to principle. We have been eroding the key distinction, as famously attributed to Voltaire, of “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” Political winds shift. Taboos change. Without protection of speech, the censors of one era could find themselves censored in the next.

The UNC faculty are to be commended for upholding the greater principle at stake. They are protecting the university for years to come.